Self-Fulfilling Prophecies: Our Invisible Sidekick

Plus, what's so interesting about Torpenhow Hill?

Issue No. 43

In the trailer for the new Formula 1 movie, there’s a scene in which the main character, a once promising driver whose career ended in injury is told,

They’re saying [you’re not just] a has-been, [you’re] a never-was.

I’ve yet to watch the movie, but presumably the main character tunes out the naysayers and pushes ahead to achieve the heights he believes he’s capable of. A positive, possibly false belief about himself contributes to a positive outcome.

But what if he hadn’t done that? What if he’d internalized that label ascribed to him, believed it, and then acted as though it were true? Things would have ended differently. In that case, a negative, likely false belief would have contributed to a negative outcome.

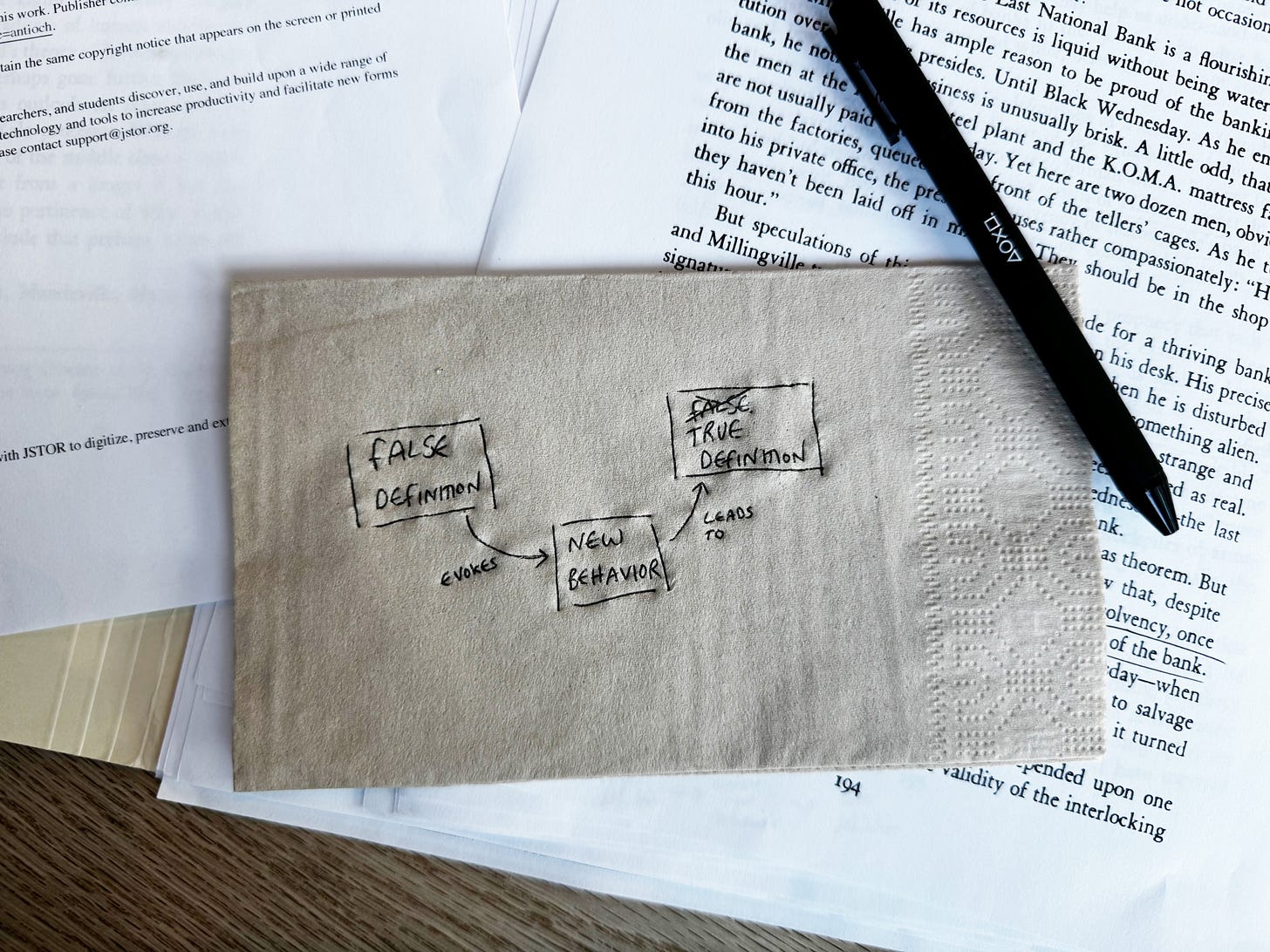

The self-fulfilling prophecy

Many of us will have heard about self-fulfilling prophecies. The idea that when we create a false belief about some outcome, the belief then sets in motion behaviors that might turn that false belief into an actual one.

A student convinced they won’t do well on an exam spends their time worrying instead of studying. When they eventually do poorly, they conclude, “I knew I wasn’t good enough.”

A rumor goes around about a bank’s impending insolvency. Fearing the worst, all its customers line up one day to withdraw their money and then, sure enough, that run on the bank causes an actual insolvency.1

Or you can imagine it applied to groups of people, where a group is described as inevitably this or impossibly that, and then members of that group see themselves in those labels.

It’s a phenomenon we see in people, and as far as I know, not elsewhere in nature. (Predictions about the return of Halley’s comet don’t influence its orbit.2) I was curious about whether it had a basis in science.

Can it influence intellectual ability?

In a study called the Oak School Experiment,3 children at an elementary school were given a disguised IQ test at the start of the year. The researchers then randomly selected about 20% of the students in each class and told the teachers that these particular students were expected to experience significant “intellectual blooming.”

The children themselves were never told anything about which group they were in. Only the teachers knew. The goal was to test whether the teachers’ beliefs would subtly affect how they interacted with their students, through things like encouragement, attention, and opportunities.

By the end of the school year, the randomly labeled “bloomers” showed greater IQ gains than their peers. The researchers concluded,

When teachers expected that certain children would show greater intellectual development, those children did show greater intellectual development.

Can it go as far as alter our physiology?

In a 2018 pair of studies,4 participants were told they’d learn about their genetic profiles, and in particular their propensity for obesity (whether they had a gene that made them feel full) and their capacity for exercise (whether they could handle harder workouts).

For the obesity study, participants were asked to eat a meal, and their blood was measured for molecules that indicated hunger or fullness. For the exercise study, participants were asked to run on a treadmill and their cardiovascular profiles were measured.

A week later, they were asked to come back and to redo the task. Right before they ate the meal or got on the treadmill, depending on which group they were in, the researchers shared with the participants their genetic profiles.

Only the profiles were made up. Some who had the protective gene were told they had the at-risk one, and some who had the at-risk one were told they had the protective one.

What the researchers found was that sharing that information alone changed how people performed on the second task relative to their numbers from a week earlier.

Those who were told they had a version of the gene that made them less prone to obesity actually performed better after the second meal. They produced two and a half times more of the fullness hormone, even though the meal was identical to the one they’d eaten the week before.

People told they had a gene that made them respond poorly to exercise then went on to do much worse on a challenging treadmill test. Their lung capacity was reduced, they were less efficient at removing carbon dioxide, and they quit the treadmill test sooner. All indications were that the people were in worse shape than they were before learning of their fictitious genetic risk, in accordance with what participants were told about their genetic risk for exercise capacity.

The mere belief about their genes altered both their perception and their biology.

[T]hose informed that they had the high-risk gene always had a worse outcome than those informed that they had the protective gene, even though we essentially drew out of a hat which information people received.

—Stanford researchers found that receiving genetic information can alter a person’s risk (study by Alia Crum and team)

Takeaways

Belief, good or bad, can contribute to outcome. Unhelpful thoughts can constrain us, and helpful ones can up-level us. It’s crucial we realize the effect of how we talk to ourselves about ourselves. If you’re playing volleyball and you realize you’re messing up during a game, telling yourself under your breath, “I’m terrible,” might eventually contribute to you becoming that.

Expectation is not evidence. Don’t let someone else tell you what you are or aren’t if the intention is to limit you. Someone else’s belief isn’t your reality. It’s only realized if you let it guide your behavior unchecked. As we saw in the first study, other people’s beliefs about us can sometimes shape us in invisible ways.

Conversely, it can be helpful to surround ourselves with people who instill in themselves and in each other false beliefs that can unlock human potential. As that line from George Bernard Shaw in Man and Superman goes,

[T]he unreasonable [man] persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.

Redundant phrases

There are phrases we use colloquially that can best be described as redundant phrases. For instance,

Naan bread. Naan means bread in Persian.

Chai tea. Chai means tea in Hindi.

Lake Tahoe. Tahoe means lake in Washo.

Torpenhow Hill. This one is made up of four words, all of which mean hill:

Tor (Old English)

Pen (Celtic)

How (Norse)

Hill (Modern English)

Everyone sees what you appear to be, few experience what you really are.

—Niccolò Machiavelli (The Prince)

Until next time.

Be well,

Ali

P.S. Some past issues to read through in case you missed them.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is a recent example of exactly that.

https://entrepreneurscommunicate.pbworks.com/f/Merton.+Self+Fulfilling+Profecy.pdf

https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2018/12/receiving-genetic-information-can-change-risk

https://people.wku.edu/steve.groce/RosenthalJacobson-PygmalionintheClassroom.pdf