Issue No. 36

In this issue, I discuss imposter thoughts with Prof. Basima Tewfik. What constitutes imposter thoughts, what exacerbates them, how they interact with interpersonal skills and employee well-being in the workplace, and the unexpected upside they can have.

Basima is a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management. Her research investigates workplace impostor thoughts—the belief that others overestimate our competence at work—and request-declining at work—the active decision not to help others at work. She received her PhD in management (Organizational Behavior) from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and her AB, summa cum laude, in psychology with a secondary degree in economics from Harvard University.

You can watch our conversation by tapping the play button at the top. Substack auto-adds closed captions to videos, so they won’t be perfect. The edited and annotated transcript is below. The video will be cross-posted to YouTube.

(Note: This issue is too long for email. Click the View entire message link at the bottom to read the entire issue on Substack.)

Others at work perceive employees who more frequently entertain workplace imposter thoughts as more interpersonally effective. This is because employees who more frequently entertain such thoughts adopt a more other-focused orientation in response to the threat to self-esteem that such thoughts trigger.

A brief intro

The label for this phenomenon emerged in the ‘70s when two professors at a college in Ohio began to notice a pattern in their female students. The students were convinced they’d only been admitted to that college because they’d somehow fooled the admissions committee into believing they were smarter than they actually were.

The researchers published a paper in 1978, defining for the first time what they’d seen with that group of students.

The term “impostor phenomenon” is used to designate an internal experience of intellectual phoniness that appears to be particularly prevalent and intense among a select sample of high achieving women.1

The more sensational term syndrome eventually replaced phenomenon, no doubt causing a great deal of harm in the process—a situational experience became a pathological designation, leading to people sometimes confusing and conflating it with other phenomena.

For instance, the feeling of being an outsider isn’t necessarily the same as having imposter thoughts, though it may be a byproduct of it. Similarly, affects like the fear of being found,2 or the anxiety that comes with a tender self-esteem may also be byproducts of imposter thoughts.

As Basima reminds us in her writing, the central feature of imposter thoughts is the belief that others overestimate our abilities.3

Transcript

How do these thoughts get into our heads?

Ali (0:0)

I thought I would start with highly competent people who have had these imposter thoughts.

One of the things I was doing as I was prepping for today is I looked up all the people who on the outside you'd think are successful or who have made it in life. And then I wanted to see if they'd written about their own feelings of self-doubt. I want to read you one quote from Maya Angelou. She says,

I've written 11 books. But each time I think, uh-oh, they're going to find out now. I've run a game on everybody. They're going to find me out.

How do these thoughts even get into our heads?

Basima Tewfik (0:56)

That's a really interesting question.

I think it's first helpful to start with what I think those thoughts are. So almost providing a definition. And then I can talk about what the academics would call the antecedents. So what are the precursors of these thoughts?

When I hear a sort of statement like that from Maya Angelou, I kind of think of what I call workplace imposter thoughts, which I define as a belief that others overestimate your abilities or talents at work. It's this idea that, you know, maybe I was capable in the past, but now other people are sort of expecting me to be this level of capable every single time.

And so for Maya Angelou, I think what she's getting at, obviously I'm not Maya, so I can't say exactly what's going on in her head. But this kind of idea of—I had a lot of success, and so I kind of feel this pressure to keep performing at that level that I believe others expect me to be at.

But what's actually driving imposter thoughts, or what I think makes imposter thoughts particularly interesting, is this idea that we know all of the things that we're not good at. We understand ourselves, we remember every failure, every moment of doubt that we've had, every time that maybe we didn't do as well as we thought we could on a particular task in the past.

Everyone else is not necessarily privy to all of those sort of thoughts or all of those past experiences. And even if they are privy, they might not assume that those are that important or diagnostic of whatever task you're supposed to be doing next.

And so for Maya, she's potentially thinking, okay, I think there's this like crazy high level of expectation of what my capabilities are. I understand maybe that I have been successful in the past, but maybe as I was engaging in that sort of performance that they're evaluating me on or using as information, I remember what components were luck-driven—where I got lucky—where things seem to just fall into place. And I also remember the little stumbles or missteps that occurred in that performance that maybe other people aren't picking up on.

Are imposter thoughts always about the fear of being found out?

Ali (3:07)

I want to go back to that definition you gave. You talked about this gap between how we think of our abilities and how we think other people think of our abilities. That gap is what leads to imposter thoughts. I've heard you share that that's the central feature of this feeling, rather than terms that we sometimes hear like “phoniness” or that “we're faking it.”

Is that generally accurate, that that's what we really mean when we talk about imposter thoughts?

Basima Tewfik (3:39)

This is also another excellent question. Part of my impetus for studying this phenomenon is the fact that there are so many different definitions that are floating around. And in part, this is because a lot of the discussion around this phenomenon is happening in the popular press.

And when you're talking to a mainstream audience, there are other things that we might care more about, like making sure people are understanding what we're talking about, as opposed to maybe being really precise, which is what I think academic scholars try to do.

They're like, no, we're talking about this and not this other thing.

And so when it comes to faking it—the idea that I'm going to get found out—I think that it is likely a byproduct of having these thoughts, of other people thinking I'm smarter than I am. When I was early on in this research, I was trying to figure out, is the fear of being found out part and parcel of the contract?

Does it have to always come together with this idea that other people overestimate me or can it be a byproduct? And I did some initial qualitative interviews right at the beginning.

And what I noticed is that there were some people that said, yeah, I mean, other people overestimate me, but, you know, I'm going to just ride this out until they catch me. So they weren't necessarily indicating that they have this extreme fear that is paralyzing them. They were just saying, yeah, maybe this is happening, but I am getting some benefits and I recognize these benefits. And so let me just see where it goes.

This introduced this idea of, wait, might these actually be separable? And for some people, we see that fear really driving their subsequent behavior, but for other people, maybe it's actually motivational or something else is going on, driving potentially positive effects.

That initial kernel is what led me to start going down this pathway of, do we actually have a misunderstanding, or an incomplete understanding, of what this phenomenon is. We've all been focusing on this fear pathway, in part because people tend to conflate the fear of being found out with the idea that others overestimate you. But might there also be another pathway that's operating?

Labeling things

Ali (5:54)

I love how precise you are. In recent publications that I later learned had been read widely, I noticed they focused on “phoniness” and the “fear of being found out,” so there’s definitely that conflation happening.

I looked at the usage trends for imposter thoughts, which is what you talk about, specifically in the workplace, imposter syndrome, and imposter phenomenon, which is what it was called in the original ‘78 paper. And syndrome is way, way up, and everything else doesn't even show up on the graph. Was that definition used because it can be sensationalized—because it can create a reaction in people—more so than something that's more dry and academic?

Basima Tewfik (6:49)

I love talking about language. It's not necessarily my expertise, given what I study, but it's something that I've been thinking about a lot. And there's a reason why I chose to use the term thoughts, as opposed to some of the other terms that you're seeing floating around.

So a little bit of background on this phenomenon and language, as I understand it. The ‘78 paper introduced this idea of imposter phenomenon. In the early ‘80s and mid ‘80s, a lot of these scholars who were working on this contract, especially the seminal scholars—the original scholars of this work—decided to go the non-academic path. They decided to write a popular press book.

And that popular press book used the words imposter phenomenon. But I think when they were loosely talking to people more broadly, they would sometimes introduce the term syndrome.

I can only speculate as to why syndrome has really taken off. I think part of it is we like to diagnose ourselves and syndrome feels medical. It feels clinical. It feels like I can say, oh, I have this thing and other people don't have this thing. But even the original scholars, Clance and Imes will say that they made a mistake by using the word syndrome. And the reason for that is if you think about the word syndrome, it's kind of trait-like. What that means is it's this idea that it's going to be stable.

Syndrome also suggests that there's sort of a constellation of particular characteristics. And that's not necessarily the case that everybody is going to hold all those characteristics. So we can even go back to the distinction we just made a minute ago between the idea that others overestimate you and this notion of the fear of being found out. If you're thinking about it as a syndrome, you're then going to say that everybody necessarily needs to have all of those characteristics, which may or may not be true, just like the story I told you about the person who has the thoughts, but doesn't necessarily feel the fear, or at least to the same extent that maybe others might say that they do.

At the same time, when you have that really catchy term of I get to say I have imposter syndrome and you don't have it and I have it, I really think this is something that the media caught up on. It's something that the everyday person found sexy and interesting.

And so that's why we're seeing it. What's interesting, though, is in the academic literature, particularly within the last five years, you are starting to see many scholars, including me and others, who are starting to say: actually, this can be a state.

That is, this can be something that you experience sometimes and not other times. And that notion, by the way, is not completely crazy or new. If you look at the ‘78 paper, they say that some of the patients—the clinical subjects in their population—didn't necessarily experience this all the time.

They would talk about very discrete experiences and what they experienced and how those thoughts drove their behaviors. So when I tackled this phenomenon and decided to reintroduce it to the management literature, I was very purposeful in choosing my terminology. And there's a couple reasons for that.

One is trying to push back against the popular narrative.

A lot of my research is trying to figure out what are things in the popular narrative that we think about that may not necessarily be true or at least not wholly true. Another part of it is to help scholars get really clear about what they're talking about.

Because most of the discussion is happening in the popular press, as scholars, we're not immune to what's going on in mainstream discussions, right? So we also might be reading those mainstream discussions and using those mainstream discussions to characterize or help us understand the phenomenon that we're looking at.

And so part of it is me saying, okay, I'm using thoughts. When I use that, that's to help you distinguish it from a bunch of other conceptions that you might be thinking about. But I'm going to be really clear about the fact that when I'm talking about it, I'm talking about this idea of others overestimating your abilities.

Associations and connotations

Ali (10:53)

If I hear imposter syndrome, the first thing I want to do is Google it. I’ll then get a list of symptoms, so I’ll say, well, I have all of these, or I think I do. Or if it's some other syndrome, again, I’ll Google it, and say, yeah, I definitely have all of these.

Like you said, you self-diagnose yourself. That is the danger.

Basima Tewfik (11:17)

And I'm sure medical doctors everywhere are like the advent of Google, good in some ways, maybe not so great in other ways. And my patients come in and are like, I have this disease. Yeah.

Ali (11:27)

I've been there. I mean, with Google and other websites [Reddit] where people share anecdotes about their health conditions. You have this bias where you identify with those things, even if you don't really have them, or if you have them in varying degrees, you assume you have them to the same degree.

Basima Tewfik (11:47)

As humans, we enjoy categorizing ourselves. We enjoy categorizing others. Anytime there's an opportunity to put myself in a category, I might have this urge or motivation or at least liking of this opportunity to do so.

The other thing I always think about with language with this term, and I don't know if this is where you want to go, but it's the connotations.

So when you think about the words imposter syndrome, there's some very strong connotations for both of those words. For imposter, it brings back negative ideas. It's this idea of, oh, I'm a swindler. I'm sort of a grifter or whatever it might be. And syndrome, again, sounds like a medical condition. It’s not good to have some sort of syndrome.

The other thing my research is trying to say is that this is another misconception that probably comes from the words themselves. We assume if I tell you something is imposter syndrome, that it [necessarily has] all these negative associations.

And so it's perfectly normal for me to think that this is a really bad thing to have. And for all of us to start to think, oh, this is something I need to overcome. This is so bad.

Ali (13:05)

I got thinking about imposter as well. And I thought, yeah, that has issues too. And I got thinking, well, if I were to rename it, what would I call it? And I don't know what you think of this, but how about perceived overestimation bias or overestimation bias? Just so that we’re clear about what the thing is instead of alluding to some metaphor or some other image.

Basima Tewfik (13:29)

I would love that. I think that's great. The only thing that I would say about that is it leads us to having a big discussion about, well, is this related to confidence or under-confidence or something like that, which is a whole other discussion. And there are some great scholars at Berkeley and other places who have been studying overconfidence.

And they really use this word of overestimation. So, yeah, specific words just take you on different paths and potentially bring to mind other associations with other concepts.

How are things named in the field of psychology?

Ali (14:04)

I don't know much about psychology, but I'm wondering, is there a regulatory body that decides what to call things or do scholars publish a paper and decide what something ought to be called?

Basima Tewfik (14:17)

It's pretty funny. As academics, we come up with our terms and we hope that other people will agree with our terms! There is obviously the peer review process and I'm sure some reviewers might push back on certain terms.

But I actually think this is why we have so many terms that some people are like, this seems really imprecise or this seems more precise or less precise. Even if you think about imposter phenomenon, part of the reason they switched over to syndrome is because phenomenon is such a broad term.

It's almost like, what does phenomenon mean? And so I think part of probably why we're seeing this evolution in terms of the terminology is because it started off so general, in part because that's almost a safe term to use maybe. Reviewers are less likely to push back like, oh, yeah, it's a phenomenon, and they called it imposter. Okay, that makes sense. And now you're starting to see people being like, no, no, no, let's get really specific about what we're talking about here.

Do imposter thoughts originate in early childhood?

Ali (15:19)

I read somewhere that these thoughts can start in childhood, when a child is overpraised, when they're told they're great at everything, or when they're labeled. Like we were saying, you turn into your labels sometimes. Do we still believe that's the case, that these thoughts could begin in childhood?

Basima Tewfik (15:38)

That is super interesting. So I suppose typically I have not looked at the history of childhood antecedents. We do know that there is literature. I have a review paper that came out in January that combed the psychology, education, management, medicine literature. Some people do suggest that parental styles or things that happen in the classroom could be precursors.

When I'm thinking about an antecedent, I think it needs to meet two different criteria. At least two. The first is this idea that you've had some success. And the second is that you've received feedback on that success.

So if you've not received any feedback on a previous success, then you're unlikely to experience these thoughts. And so this is another thing that really was puzzling for me when I first started thinking about this phenomenon, because if we think it's something that you need to overcome, but if I'm telling you at the same time, people who are successful have experienced this, it introduces two questions. Did these people succeed in spite of it? Or might it actually be something that helps them or at least hasn't necessarily hindered them along the way?

What that leads us to think about is that it’s something that capable people experience. That it’s a natural part of a capable person's experience, especially if they're putting themselves in a growth situation.

Are they more prevalent in creative fields?

Ali (17:11)

One other question, and then I'll move to the workplace, which I know is where your research is in. Is it fair to say that people in creative fields4 are maybe, I don't know if I would use the word more, but let's say more prone to imposter thoughts because others might read things into their work?

Say I put out a movie and then someone reads some hidden message in it that I didn't intend. And then I'm faced with this dilemma. Do I own up to it and say that I actually meant the simpler, plainer message? Or do I pretend like, yeah, I'm as deep as you think I am?

Basima Tewfik (17:52)

I love this question. So I, okay, a couple of things. When we think about being prone to something or if I'm thinking about where I’m going to go out in the world to study this, I'm going to study it in fields in which there is a subjective standard of success. In that sense, creatives could be a great space to look at. I wouldn't necessarily say that creatives are more prone. It's just that creatives are likely to experience this.

Maybe because of exactly what you just said, which is that there isn't this gold standard of what the best work looks like, what the next best work looks like, and what the third best work looks like. Really, they're actually evolving standards. It's influenced by the current zeitgeist.

In that sense, I would think that creatives are likely to experience it, or at least I definitely would go about studying them.

I actually do have some ongoing work which I hope to talk about more when it gets through the peer review process, but really looking at this connection between workplace imposter thoughts and creativity.

Because something that you've just suggested is, is it because I'm a creative that leads me to have workplace imposter thoughts? I kind of think about it may be in the opposite direction, which is that it could be that workplace imposter thoughts impact creativity. Whether it's Big-C creativity or everyday creativity that we're all engaging in. I argue that imposter thoughts might sometimes be beneficial for that everyday creativity.

Finding one’s calling in life

Ali (19:46)

Wonderful. All right, I know we've got maybe ten minutes, and I wanted to move to the bulk of your research, which is about imposter thoughts in the workplace. I heard you say in an interview that you were working as a management consultant, and it was at that point in your life that you started thinking about imposter thoughts. And so you went to graduate school and started doing research in that field.

And one of your findings off the back of that research was that imposter thoughts aren’t all bad. That if we have imposter thoughts in the workplace, there are actually some positive effects that we get.

Basima Tewfik (20:33)

Let me tell you a brief story of the journey and then dive into that piece of research, which I'm very excited about. I had done some research as an undergrad in what is called micro-organizational behavior, which is what I call the psychology of work. But I decided that I wanted to go into general management consulting. And so that is what I did post-graduation.

I moved to Chicago, joined an awesome firm, and in that experience, I was working on a lot of different teams. And I realized that while the client work was interesting, what was more interesting was actually analyzing the dynamics of the teams I was on and just seeing how work functions and how people navigated their work lives. And so that pushed me to go back to grad school.

In my first year of grad school, we had a series of classes. And one of the classes was about practicing to write a full academic paper as if you had already done a ton of research and you were writing it up. I had gotten the advice to use those classes to study something I was actually interested in.

And so for the first three weeks of that class, I kept sending little memos to a professor in the department being like, What about this idea? What about that idea? And I kept getting, Nope, not good. Nope, try again. Nope, try again.

And then I remember sending an email about imposter syndrome, in part because I am what I study. And I think a lot of people have experienced this. And I basically got an email going Bingo! So I was like, okay, this is it.

But I then quickly realized that the research wasn't quite there. So this is how I came to the conclusions of what we talked about earlier about how a lot of this work is happening in the mainstream, and not necessarily in scholarly journals.

That actually led to some funny moments of professors coming into my little cubicle and seeing New York Times, Cosmopolitan, and then … an academic journal. And they're like, what are you doing? I'm like, No, no, no, I'm really looking into this phenomenon, I promise. I’m really trying to get an understanding of it!

Imposter thoughts in the workplace have an upside?

One of the things I was trying to figure out was, What are some big misconceptions? We've already talked about a few. But the first one that I really wanted to tackle is exactly what you just mentioned, which is this idea of, Can imposter thoughts have upsides?

And so I did a number of studies. The first study was a Finance firm based in the Mid-Atlantic region. And there I just wanted to see proof-of-concept. Could we see that people who had imposter thoughts for these Finance employees, could they be potentially rated as more interpersonally effective, controlling for things that we might care about? So could I rule out things like, oh, well, maybe actually they're being rated as more interpersonally effective because they're actually just better performers or maybe, you know, they're actually just more experienced or whatever it might be.

I found that Finance employees who thought that others overestimated them at work seemed to be rated by their supervisors as more interpersonally effective. So I was like, this is great. Amazing. Let's go to the next stage.

Studying physicians-in-training

I happened to be friends with a number of people in the medical field. I'd been chatting to them about this research that I'm doing. And they were like, You should study us. And I was like, OK, well, let me look into this.

And this led me to partner with a medical school that had these sort of patient simulations. So as part of medical training, essentially these doctors in training (it could also be doctors later in later stages of their careers) would interact with standardized patients.

Standardized patients are basically people from the local area. They tend to be actors in real life. So maybe they also work in theater in the city. And what's great about these standardized patients is they truly are standardized. What that means is they actually all get trained to act as if they have certain symptoms.

They get trained on exactly how to respond to questions and so they're all interacting in the exact same way. When they're not interacting with a patient, they're sitting in this control room, which I can describe because I also sat in this control room. It basically had a bunch of videos and you could listen in on other people's interactions to make sure that when it's your turn to go into a room, you knew exactly how Joe and the other session interacted.

What that meant is that everything that was happening in that interaction was going to be happening on the doctor's side because the patient side is very controlled. So anything I see, it's not because the patient was acting differently. It's probably something with the doctor.

So with the doctors, I was like, okay, it would be really cool to study doctors who have imposter thoughts interacting with these patients because it's a very standardized experience. And so I can diagnose or at least figure out what is happening as a result of having imposter thoughts.

With these doctors, about a week before the interaction that they all had to go through, I asked them to give me their sense of imposter thoughts. And then during the interaction, we actually video recorded a portion of these interactions. And then for all of the interactions, patients were trained to give interpersonal effectiveness ratings for all of these doctors. And then I also asked the doctors to give me a sense of what diagnosis they would give for each of the patients.

What I found was that doctors who had more frequent imposter thoughts were rated as more interpersonally effective by these patients. They got the diagnoses more or less correct, which is good because, you know, if they're warmer or great to be around, that's not so great if they get the diagnosis wrong. So we weren’t seeing that to be the case.

What I found was that doctors who had more frequent imposter thoughts were rated as more interpersonally effective by these patients.

And then when we analyzed what was actually going on in the video—we had an awesome team of MIT and Wellesley RAs who coded the behavior—I saw that those who had more imposter thoughts—those doctors who expressed those thoughts—were being much warmer in conversation. So much more other-oriented.

They were making a lot of hand gestures. They were doing better eye contact. They were nodding a lot more. Then I did two subsequent experiments to really get at causality to really show that this seems to be the case. But essentially, [the takeaway is that] if you have imposter thoughts, you are more other-oriented. And as a result of that other-orientedness, other people are seeing you as a better person to work with.

Ali (26:52)

Fantastic. Wonderful. So to summarize, doctors with imposter thoughts were as competent, but more interpersonally effective.

Basima Tewfik (27:00)

Yeah, that is a great summary. It's like, perfect.5 I’m always happy to get into the nitty gritty. But I love that clear line.

Better interpersonal skills as a defense response

Ali (27:09)

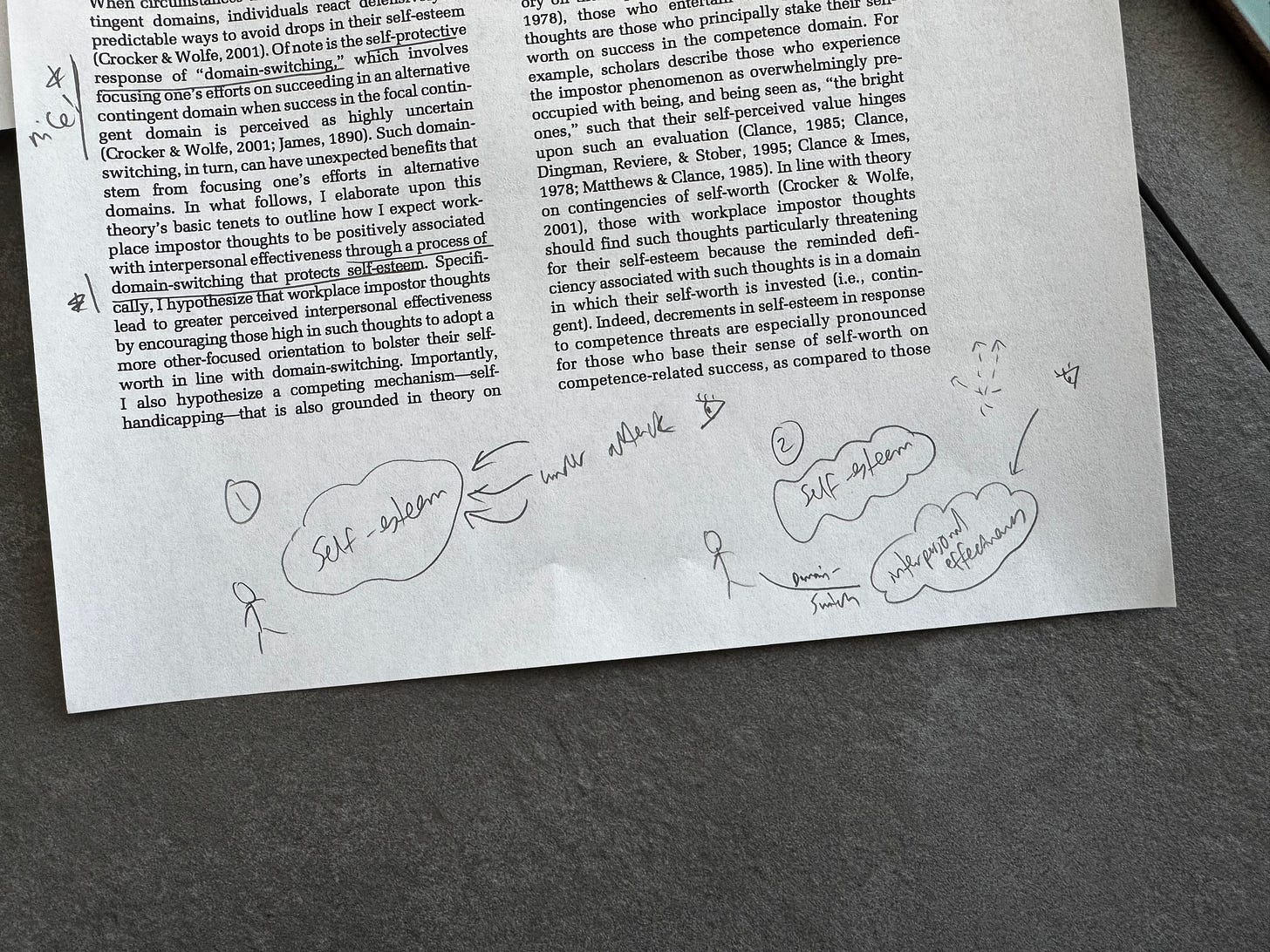

I love that in one of your papers, you talk about it as a defense response. I think you used those words. And it got me thinking, that's a good pattern for a lot of the things we experience. Actually, I have the paper here—you say (paraphrased), we feel our self-esteem is under attack, and so we domain switch, and put out interpersonal effectiveness to feel better, or to maybe mask that attack or to deal with it somehow.

Basima Tewfik (27:37)

Yeah, the theory of what I think is going on is that it's almost a subconscious process. Whenever we feel our self-esteem being attacked, we naturally do a bunch of things to try and get our self-esteem back to the level it was or to protect ourselves.

Most people think of maybe self-sabotaging or self-handicapping as a potential pathway or reactions you have to this. But we also have some pretty adaptive things or things that we might not realize are adaptive. And domain switching is one of them.

If we think about the two key domains of life, there’s our ability domain and our warmth domain. And so essentially what we're seeing here is potentially this trade-off of—I think other people think I'm not as smart, so let me turn up the warmth and then see where that goes.

Do we know if it helps us with career progress?

Ali (28:31)

Wonderful.

All right, just to show you what an amateur I am, Zoom is telling me that my call will end in seven minutes because I didn't pay for the paid plan! So maybe just two more questions.

The first question is actually the main thing I was wondering about a few years ago when I got thinking about this stuff. You talk about imposter thoughts having this upside, making us more interpersonally effective. But more concretely, does it also help with things like career progress or promotions at work?

Basima Tewfik (29:11)

That is something that I have been thinking deeply about. So the way I would tackle this is [like so]. If you have a high interpersonal component at work and your performance is more subjective, as in, you're not in a factory where [you’re working on a] set of widgets where people can really count and say, okay, you made 10 widgets today and yesterday you made five widgets. I think it can be a pathway to success because there tends to be a halo effect—I think you're a nice person to work with and so I'm probably more likely to also rate you as higher on other sort of dimensions.

What's particularly tricky is in most places, you're not going to be able to disentangle this because of the halo effect. So most people who are rating you under relationship skills are probably also the same ones rating you on your project skills. What this means is, yeah, I do think imposter thoughts can be what helps you get there. But I also think you have to be in the right condition.

Another way of thinking about your question is thinking more broadly about what are, maybe, three things we care about at work. One, we probably care about your job performance. That's always a big one. Two, we care about your interpersonal skills. And three, we probably also, at least to some extent, care about employee well-being, because if our employees are not feeling good, it's likely to impact their performance.

What my research suggests is that imposter thoughts can be really good for your interpersonal performance. The effects on job performance are a little bit more contingent. So if we're thinking about it through operating through interpersonal performance, it could be good for your job performance, but we're not seeing a strong relationship.

It suggests that there are situations that can make it good or bad. But then another thing to keep in mind is that it's not always good for your well-being. What I mean by that is we do know that imposter thoughts cause anxiety. You're more likely to report that you are less satisfied at work, that you're less committed.

If we're putting all those things together, what it means is that I probably want to think about where you sit in an organization before saying that, hey, I think your imposter thoughts are going to be good for your performance versus not.

If you’re a solo entrepreneur or you are a software engineer who's not really interacting with others, say you're working on a particular piece of code. And that is where you're sitting. And you don't really interact at work with anybody. And maybe you live at home by yourself. For those people, I'm going to be particularly worried if they have imposter thoughts because they're unlikely to get the interpersonal benefits because they're not getting feedback from others that, hey, you're a great person to work with. They're not having those interactions to help buffer their self-esteem and do that trade-up.

From an employee well-being perspective, they're likely to feel anxious because they're not able to buffer. And so what we would expect then is that this is probably going to have downstream effects on job performance in a negative way.

I probably want to think about where you sit in an organization before saying that, hey, I think your imposter thoughts are going to be good for your performance versus not.

Now, let's take a different type of person. Let's take a person who is maybe the lead of a team. They're in the office five days a week. Their whole team is in the office. And a lot of their work is very interpersonally oriented. For those people, what you're probably going to see is that interpersonal benefit. You are probably also still going to see a hit on employee well-being because that seems to be consistent. But the idea is that maybe that interpersonal benefit is going to at least cancel out or help offset some of that well-being.

And as a result, maybe their job performance is actually going to be pretty good too because it's being fed by their interpersonal effectiveness. And so overall, the net benefit for them might be significantly higher than the first employee I talked about who's the solo entrepreneur or the software engineer.

It's a little bit more complicated.

Ali (33:07)

It always is. That was really insightful, Basima, Thank you very much. I really appreciate your thoughts. And I'll link to your work. I'll link to the measure for imposter thoughts that you share in your papers that helps us figure out if maybe we fit into this category and then add some notes around your work.

Basima Tewfik (33:33)

Thank you so much. It was really great chatting.

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

—Ludwig Wittgenstein (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus)

Until next time.

Be well,

Ali

P.S. Welcome to all the new subscribers who join us from

and . Thank you for the recommendations. And thank you to everyone who continues to share these issues.The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1979-26502-001

Why Everyone Feels Like They’re Faking It, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/02/13/the-dubious-rise-of-impostor-syndrome

The impostor phenomenon revisited: Examining the relationship between workplace impostor thoughts and interpersonal effectiveness at work, https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=dDV4dYoAAAAJ&citation_for_view=dDV4dYoAAAAJ:UeHWp8X0CEIC

I had wondered if being a generalist makes one prone to it as well. When you know a little about a lot, you might feel like you’re never truly an expert in anything. With the advent of AI tools, it feels like we’ll end up with more generalists in the labor market.

I also wonder if being the first or only in a room, say at work, also exacerbates it. Or being perceived as a subject-matter expert where people might assume you know more about something than you actually do.

I experienced this when I published Bad Arguments, which was a website that looked like a book, and later became an actual book. People would interview me and ask things like “Who are you reading these days?” or “What genre do you prefer?” And I wasn’t really much of a reader at that point nor did I, frankly, even consider myself a writer.

This is going on the back cover of my next book. “Perfect!” :) I’m always suspicious of one-word blurbs on book covers or in movie promos. If a movie poster says “Exceptional!” I wonder, what if that was pulled from a review written by a Gordon Ramsey-type person: “This movie was exceptional … in how terrible it was.” “This movie really moved me … to a continent where they don’t play movies.”

Share this post