The Sunk Cost Fallacy and How It Influences Our Decisions

What makes us stay in a job we don't like, for instance?

Issue No. 13

A sunk cost is the price you’ve already paid for something, in terms of time, money, or effort. It’s in the past, it’s irrecoverable. An opportunity cost is the price you’re hypothetically paying for not doing something you could be doing, but aren’t. Likely because you’re bogged down with something else that’s taking up your time, money, or effort. This issue is about the opportunities we lose out on when we’re hung up on the past.

Once upon a time, it hit me that Franz Kafka was by day an insurance officer. Sitting behind a desk, stamping policies. Exposed to all the mundane details of an office job. Working on PowerPoint presentations, probably. Slacking off on Slack. Hanging out by the water cooler, talking someone’s ear off about salesmen and insects for the third time that week. Yeah, that’s all really interesting, Franz, but, umm … I’ve got a meeting I need to run to.

And then the years went by and I learned about other writers and their day jobs. T.S. Eliot was a banker. Wallace Stevens, the Pulitzer prize winner, was a corporate executive. Chekhov was a doctor. Coetzee was a programmer.

Coetzee eventually left his day job at IBM to “drift for a while”. And he ended up doing quite well. I don’t know enough about the others to know whether they enjoyed their jobs. Assuming some did, and some didn’t, a job is one of those things where the longer a person stays in one, the harder it can be to leave it. You might realize at some point that the rational thing to do is quit, but still, the days go by and there you still are.

Given it’s the start of a new year and an apposite time to consider new beginnings, I thought it useful to cover one of the reasons why we might do a thing like stay in a job we don’t like.

There’s a type of irrational behavior known as the sunk cost fallacy, which is a tendency to continue some endeavor for no other reason than because we’ve already invested a significant amount of our time, money, or effort into it. That prior investment we made—once upon a time—motivates this now current decision we’re making to continue.1

The sunk cost fallacy in everyday life

Jobs. A job you once loved has turned uninspiring, soul-crushing. But you’ve invested years into getting good at it, you’ve sacrificed all that time away from your family, years to finally get that promotion, all that tacit knowledge that makes you a person of stature at the office and in social gatherings. What a waste it would be to walk away from it all.

Identity. An identity you’ve forged over a lifetime around some ideology is in need of a reset due to some introspection you’ve done. But you have social circles built around that identity, or you’re a public figure with followers who hang onto your every word. Will you tell them you were wrong all this time and that you’re now moving in a new direction? What a waste that would be, and what a hit to one’s ego.

Replacing an old car. You have a beat-up car that you have to take to the shop and get fixed every few weeks. A friend tells you to buy a new car. That you’ve probably spent thousands on patching your car over the past decade. You respond, “But I’ve already put so much money into it.” It would be a waste to let go of it now.

Driving. You’re stuck in traffic. It’s bumper to bumper, but you’re inching forward every few minutes. You notice that a few cars are breaking out of the lane and taking some other route. You want to follow suit—they seem to know where they’re going—but you’ve already invested an hour inching forward in this current lane. You hate the thought of losing all that sweat you put in if you leave now.2

Finishing a book or TV show. You’re halfway through an impenetrable book. You can’t, for the life you, understand what on earth is going on. You know you should stop, but since you’ve spent heaven knows how many nights trudging through, you tell yourself to get through the rest of it and see if things get better.

Food. You’ve eaten three-quarters of the food on your plate. You’re stuffed. A helpful adult at the table asks you to lick your plate clean. What a waste it would be to not eat the rest of that food.

Fixing a bad product. You’ve inherited a software/hardware product that suffers from what engineers call “technical debt”, wherein a series of bad early decisions led to myopic short-term fixes that are now causing a longterm maintainability nightmare. You propose recreating the product from scratch, but are told what a waste it would be to throw decades of work and money away at this late stage.

Relationships. A relationship isn’t working. But you’ve poured many years into it. You’ve built a house, bought a car, cultivated friend groups. Kids, maybe. Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t, you’re told. What a waste it would be to leave it all behind.

In the lead-up to Princess Diana’s wedding day, there’s a scene where Diana is talking to her sisters, and let’s them know she doesn’t want to get married anymore having just made an ominous discovery.

So I went upstairs, had lunch with my sisters who were there and said: ‘I can’t marry him, I can't do this, this is absolutely unbelievable.’ They were wonderful and said: ‘Well, bad luck, Duch, your face is on the tea-towels so you're too late to chicken out.’

—Andrew Morton (Diana: Her True Story)

Though the line was likely flippant, one can imagine how a set of already printed tea towels could have been used to inform the current decision to back out of an impending marriage.

The common thing in all those examples is a decision being made in the present that’s influenced by a pull from the past—a desire to not be wasteful and to minimize loss due to time, money, or effort you’ve already invested in the thing. That’s effort that’s not recoverable. It should have no bearing on this new decision. But it does have a bearing. In each of the examples, you’ll notice an opportunity is wasted (the opportunity cost).

With the dead-end job, a person loses out on a better, more fulfilling calling in life.3

With the ruptured identity, a person loses out on actually arriving at the truth.

With the bad relationship, a person loses out on the serenity and wellbeing that one gains from having a true partner.

With the beat-up car, a person loses out on treating themselves to something that could lead to an improvement in their quality of life.

And so on.

That desire we experience to not be wasteful and to minimize loss has been studied. In one of ten experiments covered in a 1985 study on the topic, the authors present the following prompt to their subjects:

On your way home you buy a tv dinner on sale for $3 at the local grocery store. A few hours later you decide it is time for dinner, so you get ready to put the tv dinner in the oven. Then you get an idea. You call up your friend to ask if he would like to come over for a quick tv dinner and then watch a good movie on tv. Your friend says “Sure.”

So you go out to buy a second tv dinner. However, all the on-sale tv dinners are gone. You therefore have to spend $5 (the regular price) for the tv dinner identical to the one you just bought for $3.

You go home and put both dinners in the oven. When the two dinners are fully cooked, you get a phone call. Your friend is ill and cannot come. You are not hungry enough to eat both dinners. You can not freeze one. You must eat one and discard the other. Which one do you eat?

—Hal Richard Arkes and Catherine Blumer, The psychology of sunk cost

The authors tell us that traditional economic theory predicts that 100% of subjects ought to answer no preference. As in, it makes no difference to a person which dinner they eat. The dinners are exactly the same, after all. The results, however are as follows,

Subjects who’d eat the $3 dinner: 2

Subjects who’d eat the $5 dinner: 21

Subjects who’d eat either dinner (no preference): 66

While most subjects said they’d eat either dinner, a plurality of subjects said they’d eat the $5 one. The authors suggest that “sunk cost considerations heighten the attractiveness of the $5 dinner”, and that discarding it—as in, wasting it—is what compels so many subjects to prefer it over the $3 one. The decision is purely psychological.

The sunk cost fallacy and entrenched views

A prominent place I see sunk costs taking hold is in public discourse. The way discourse often happens nowadays is with larger than life personas, entrenched in their intellectual bubbles, who’ll talk past each other, if they even talk at all. And these personas, one realizes, are so intertwined with position and ideology, that one wonders if they’d ever be able to veer from them. I can’t remember, for instance, the last time someone said mid-interview or mid-debate, Oh, you make a good point, actually, let me rethink my own position.

Discourse is amenable to sunk costs, because our egos, our personal brands, and in some cases, our livelihoods are dependent on us sticking to talking points that we’ve become known for. If your book sales are dependent on you being pro some issue, what are the chances you’ll switch positions following an epiphany and risk alienating your audience? Integrity dictates that one does that at any point in life, but are we all willing to pay that price is the question.

One abandons that attachment to the past by accepting a life of constant reinvention, of being open to adjusting our opinions and positions in light of new realizations. Of accepting that it is possible to simultaneously be an expert and a beginner. (Otherwise, to risk ending up like this Venus flytrap that’s too committed to holding onto a chili pepper to change course and save itself.)

Is the sunk cost fallacy always a bad thing?

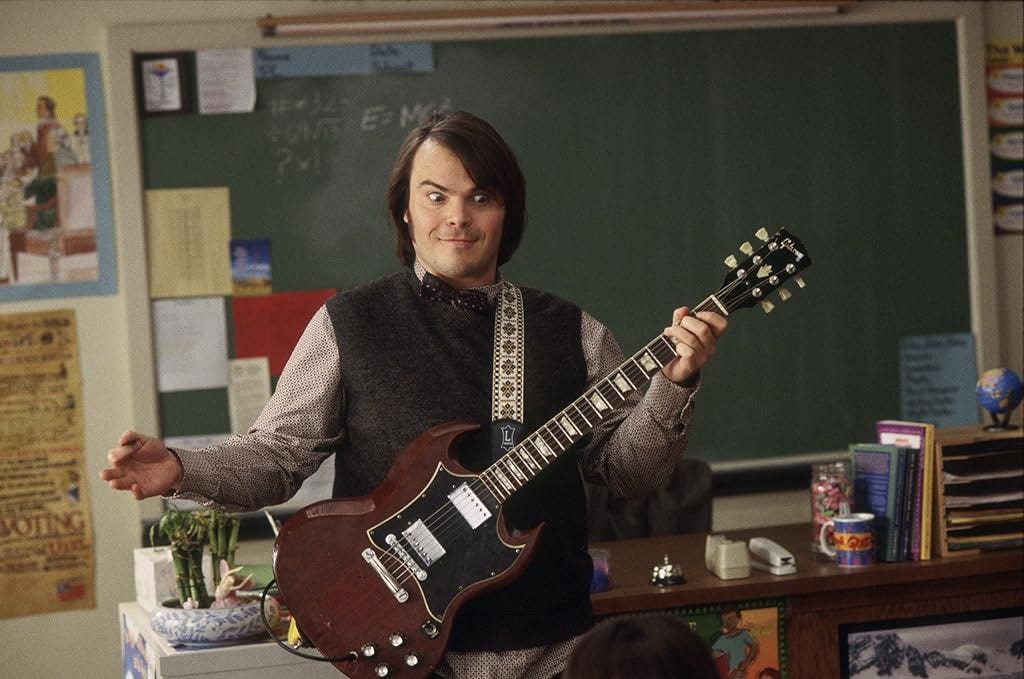

The other day, I rewatched the movie School of Rock. In that movie, you have two middle-aged men who used to be in a music band, once upon a time. One of them makes the rational choice and quits, to settle down in an apartment, find a job as a teacher, and get married. He seems fairly miserable.

The other band member (Jack Black) stays a musician, and pays the price for that stubbornness into middle-age. He’s jobless, sleeps on a mattress on the floor of his erstwhile bandmate’s apartment, and never has money to pay rent. Now it so happens that one day, despite all odds, chance smiles on him, and he appropriates a substitute teaching job. He eventually finds his purpose and is able to make a living teaching school kids music after school.

In that case, sticking to something that looked unattainable and unreasonable eventually paid off. The takeaway for me was that an irrational decision can lead to a positive outcome, despite the minuscule odds of that outcome. But the wrinkle is that one has to be aware of how minuscule those odds are and be content with them.

Here’s another story. Over dinner one night, a friend shared with me the following anecdote, which I’m retelling with his permission. This one time, he was made to go to a nutritionist to get his diet and general physical health in order. He complied. Begrudgingly. The plan was to go once, to smile and nod along, and to then not follow any of the things he’d undoubtedly be made to do.

And so he goes to that initial consult. The dietitian speaks at length, measures him, tells him what to do and what not to do. All the while, our friend is nodding along, pursing his lips—oh, I should eat more nuts? Mmyes, mmyes … consider it done, doctor. Then the session ends and he’s given the bill. The consult cost 5X what he expected to pay.

Our friend pays up, then saunters to his car. He sits down, cradles his forehead between thumb and forefinger, and falls into deep thought. His plan was to abandon any advice he’d be given, but considering he’s paid so much already, what a waste it would be for him to not heed the nutritionist’s advice and see the plan through. He’d be miserable, no doubt. But misery would trump throwing away all that money.

Is it a bad thing though, to fall victim to sunk costs in this case, considering he’d end up in better health? Probably not. But is it an irrational decision? When it’s framed that way it is. An alternative framing would have been to base the decision on future value—will this endeavor lead to better health, irrespective of what I have or haven’t paid already? If so, then I’ll do it, for that reason.

How do you counter the sunk cost fallacy?

In the same 1985 study referenced earlier, the authors found that even people who knew about economic theory were still vulnerable to the effects of sunk costs. Which means it’s not enough to know about the fallacy to avoid it. That’s disconcerting.

However, the authors do note one idea that’s worth sharing. They reference two studies that found that a person who isn’t personally involved in a situation is less likely to fall victim to sunk costs.45 As in, if it’s your money on the line, and an investment is tanking, you might be compelled to pour in more money in hopes, and on faith, that the investment recovers. Not so if it’s somebody else’s money.

So, firstly, one way of ensuring our decisions are future-looking and driven by a thought to opportunities is to frame them in the third person. Instead of talking about your investment, make it the investment and see how that impacts your thinking. Instead of it being your job that you’re sacrificing personal life for, make it the job and see if it’s still worth that trade. Instead of it being your career switch that you’re contemplating, making it a friend’s career switch. Would you give them the same advice you’d give yourself?

Secondly, base your decisions on data. Much of the metrics jargon in the corporate world (KPIs, OKRs, SMART6 goals, and so on) stem from one fundamental idea—measuring things makes it possible to know if they’re going well. When we determine early on what metrics we’re using to determine the success or failure of a thing we’re undertaking, it creates a sort of emotional distance between us and the thing. And it then makes it easier for us to abandon it when it’s not going well rather than getting hung up on it.

Thirdly, it’s useful to constantly reexamine our decisions. To talk to ourselves. I talk to myself all the time. (It doesn’t have to be out loud, so it doesn’t look weird.) Richard Feynman once said,

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.

When you’re honest with yourself—disinterested, clinical—you’re able to answer questions that can help you figure out whether you’re making a rational decision. Questions like:

Is my decision to stay in my job driven by my love for this industry or my fear of losing status were I to walk away?

Is my decision to hold onto this view driven by the fact that I’m now known for defending it so vociferously, or because I genuinely believe that all evidence still points to it being the right view?

If it weren’t my money that I was investing, but someone else’s, would I be making the same decisions about how to allocate it?

Is it time to abandon this idea considering it’s not panning out as I thought it would?

Final thoughts

I’ll leave you with a little exercise that’s always been useful for me. It might be useful for you too. Every now and again, I’ll write down a list of the things I was attached to at some point in my life that I ultimately walked away from. And I see how many of those I now regret. For instance,

In 2007, I quit a website I’d started about computers six years earlier, after I felt it had turned into a crutch that was preventing me from trying new things.

In 2010, I quit a well-paying job as a supervisor of 20+ engineers to go back to graduate school in hopes of continuing on to a Ph.D. program.

In 2012, I quit running a lifestyle business, after I felt I was being pigeon-holed into a type of work that, deep down, I didn’t enjoy.

The opportunity cost in each of those examples far outweighed the sunk costs I was attached to at the time. A person in a stable job might not take a chance on, say, starting a bakery. But someone sitting at home with no expectations on their ego might. It’s immensely liberating to base decisions on future prospects. I hope this personal experience is useful for whatever calculus might be informing your own lives.

At the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve, I was in the sky. In a plane, mercifully. It was pitch black when the flight attendant’s voice came on, letting us know what a joy it was for us all to be together on this first flight of the new year. In that spirit, let me say what a joy it is for me to be sharing this first written piece of the year with you all. I’d like to experiment with a new format where I focus on just the one topic every issue instead of three. I enjoy the long-form approach. We can see how that goes and adjust things as the months go by. Let me know what you think in the comments.

Until next time,

—Ali

P.S. Congrats to the winners for last month’s giveaway. We’ll have others this year.

Hal Richard Arkes and Catherine Blumer, The psychology of sunk cost.

This actually happened to me during a recent trip. I was in a lane to pay for travel insurance near a border crossing. It turned out that the cars who left the miles-long traffic jam and zoomed toward the crossing were able to pay for insurance at passport control. And they saved themselves an hour and a half waiting in line. But I was too hung up on my sunk cost.

Not only that, but according to a study referenced on an episode of Freakonomics (The Upside of Quitting), holding onto goals that are unattainable can lead to damaging physical effects like inflammation: You've Gotta Know When to Fold 'Em Goal Disengagement and Systemic Inflammation in Adolescence.

Barry Staw and Frederick Fox, Escalation: The determinants of commitment to a chosen course of action.

KPI: Key Performance Indicators; OKR: Objectives and Key Results; SMART: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound.

P.S. One of Toyota’s innovations is a thing called the Andon Cord. It’s a rope (or a button) that any worker on a production line can pull to stop production and let management know they’ve spotted an issue. The idea being that the earlier issues are detected, the less costly they are to fix. (The same principle applies in software.) The connection to sunk costs is that the earlier defects are fixed, the less likely it is management will be influenced by the sunk cost of leaving them.

For more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andon_(manufacturing)

Good article. Brings to mind the old saw about beating yourself over the head with a hammer. When asked, "Why do you keep on doing it?", the classic reply is that it feels so good when you stop.