Back in My Day; How Nostalgia Messes With Our Minds

What’s a reminiscence bump? And how Nestle broke into Japan.

Issue No. 39

Fifty years ago, a multinational corporation wanted to break into Japan with its instant coffee product. But the Japanese, it quickly learned, were tea drinkers. And no amount of objective research was getting them to budge.

They hire a psychoanalyst, the story goes, and he conducts a series of studies. He concludes that one thing adults in that market have in common is they have no childhood memories associated with coffee.

Work on the kids, is the recommendation, and by the time they grow up, they’ll have developed a proclivity for drinking coffee.

So the company starts marketing coffee-flavored candies to kids.

The years go by, the kids grow into adults, and by and by, the now grown-up kids turn into coffee drinkers. And the need for instant coffee is forever established.

I don’t know if this story is apocryphal. I only found it in secondary sources where it’s attributed to Nestle. But either way, it’s a great way to introduce the idea of nostalgia—the emotional bond we create with certain things early in our lives, and how those feelings color the decisions we make later in life.1

We’re more likely to remember things from early adulthood

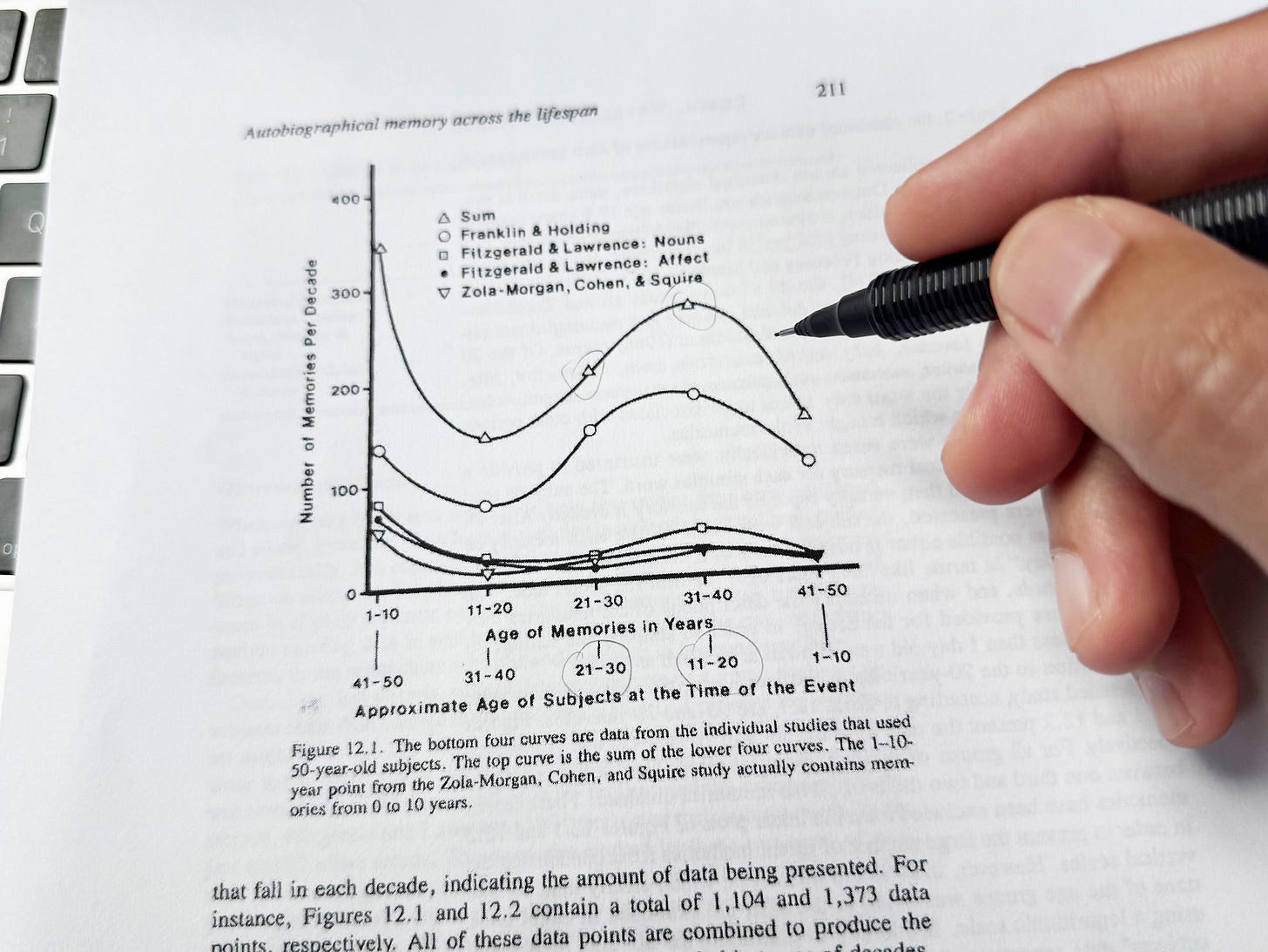

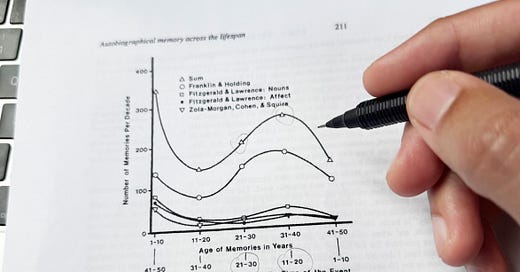

This tendency to disproportionately remember things from early in our lives is called the reminiscence bump. Named that way because if you were to plot a line of your memories, you might notice a bump in the number of ones you can remember from early adulthood.

In a study, participants in their 50s and 70s were presented with a word and were asked to provide their earliest memory associated with that word. A significant number of their memories came from their most recent year of life, which one would expect. But then, the researchers found, there was a good number of memories that came from when the participants were between 11 and 30 years old.2 Isn’t that interesting.

We’re more likely to remember happy memories over sad ones

As we get older, not only are we more likely to remember things from a certain time in our lives, but we’re also more likely to remember happier memories.

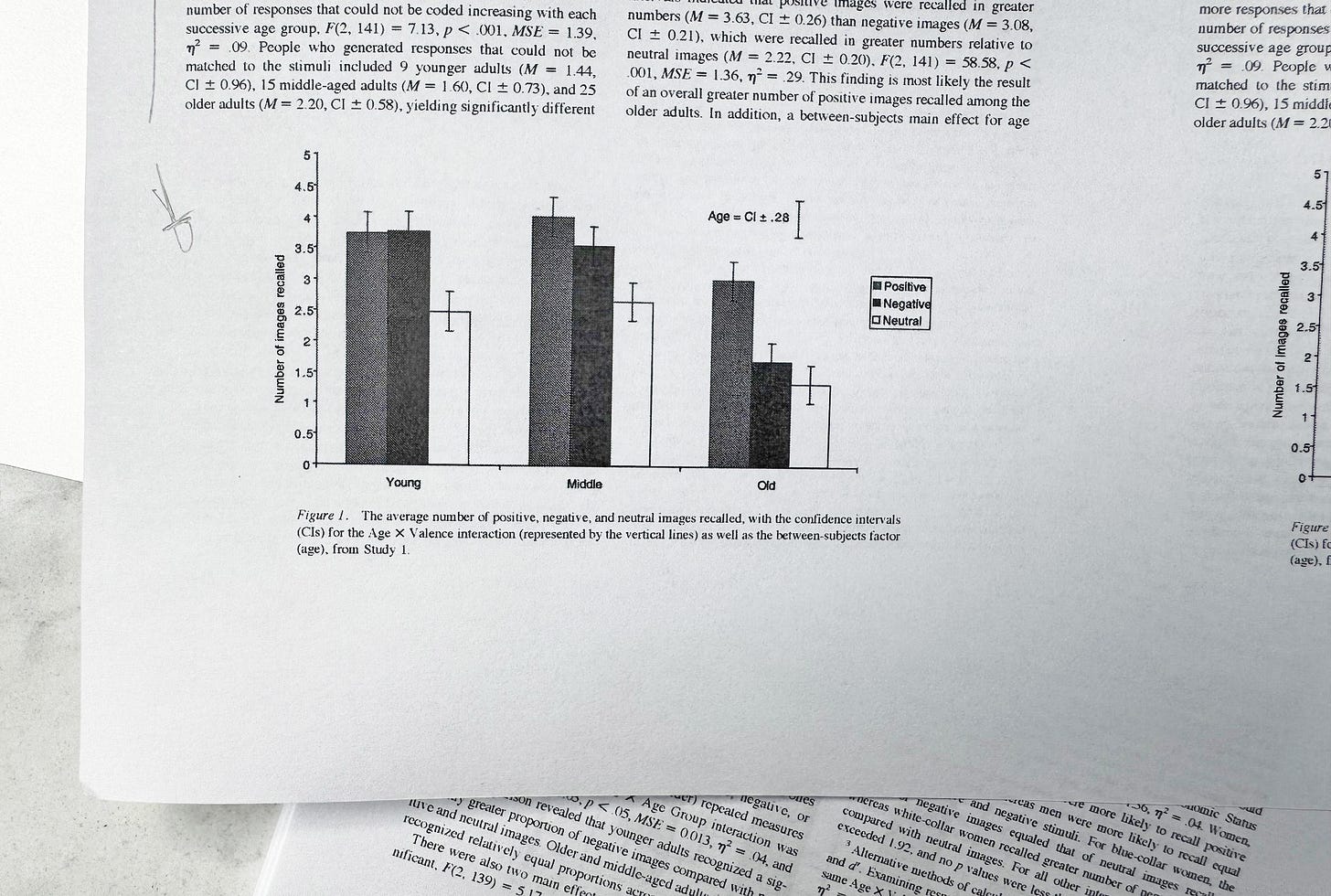

In another study, participants from multiple age groups were asked to react to a set of pictures—to share whether they felt the pictures were positive, negative, or neutral. They were then asked to take a 15-minute break and to then recall as many of those pictures as they could.

The results showed that younger people recalled a similar number of positive and negative pictures. But middle-aged and older adults recalled a greater number of positive pictures compared with negative ones. 3

We’re likely to romanticize the past

And then there’s a tendency to not only recall positive memories, but to also recast negative ones as positive ones. You might go on a vacation that’s a disaster, but remember it fondly a decade later. You might fall on hard times and have to struggle for years, but then later remember it as a time of simplicity and clarity.

In and of themselves, those retellings might not be bad. But when a distorted retelling is used to get us to act or think a certain way then they can be.

One study looked into a group of people bound by collective nostalgia—a shared longing for their nation’s better past. That nostalgia fueled not only their efforts to restore that idealized past, but also, more critically, their anger and hostility toward out-groups who didn’t share that view with them. It wasn’t just fond memories. It became a driver of hostility and group-based action.4

The long and short of it

Nostalgia isn’t a bad thing. It gives us a sense of meaning to know we’re an accumulation of good memories. A word heard, an object touched, a smell in the air—any of these can instantly take us back to a happy time in our lives. It can reduce our feelings of anxiety and loneliness, especially as we get older. And it can fuel our creativity, when we pluck something from a time gone by and apply it to something new today.

Memory isn’t reliable. Wittgenstein wrote that we make for ourselves “pictures of facts,” and that couldn’t be more true of memories. We’re prone to selecting some memories over others, we’re prone to reinterpreting them, and we’re prone to embellishing or diminishing them. Nostalgia can give us meaning, but it can also give us false meaning. The sense that a past event was coherent, when in fact it might have been chaotic, scary, and uncertain.

Nostalgia can influence our buying habits. I don’t know about you, but no amount of rational thinking will ever stop me from buying an overpriced candy molded in the shape of a Super Nintendo controller. And that’s exactly what those types of products are designed to do—to connect us to a feeling and to have us make a decision based on that feeling. We become less sensitive to price as our perceived value of the product increases.

Be wary of collective nostalgia. Personal nostalgia might be healing, but collective nostalgia, especially in politics, often serves a different purpose. If a “better past” is invoked, be cautious. Especially when that past is used to manipulate you into feeling or acting a certain way toward some out-group. Nostalgia can bring people together, but it can also divide us.

Talking of memories

I should rewatch one of my favorite movies of all time—Memento. Ah, yes. The good ol’ days of quality movies. They don’t make ‘em like that anymore.5

Hectic is this life; what amazes me

Is those who want to devour

More of it

—al-Ma’arri

Until next time.

Be well,

Ali

P.S. Check out the last two issues in case you missed them.

P.P.S. I teased an app I’ve been building in my free time on LinkedIn last week. It’s a better version of the bookshelf scanning app from last fall. More on that soon.

Credit to my wife for telling me about this story.

Autobiographical memory across the lifespan, David C. Rubin, Scott E. Wetzler, and Robert D. Nebes, https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/5a74dc57-bde3-4ea1-81f5-298a124736d7/content

“Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults”, Charles, Mather, and Carstensen, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10691119_Aging_and_Emotional_Memory_The_Forgettable_Nature_of_Negative_Images_for_Older_Adults

“Collective Nostalgia Is Associated With Stronger Outgroup-Directed Anger and Participation in Ingroup-Favoring Collective Action”, Cheung, Sedikides, Wildschut, Tausch, and Ayanian, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318862735_Collective_Nostalgia_Is_Associated_With_Stronger_Outgroup-Directed_Anger_and_Participation_in_Ingroup-Favoring_Collective_Action

Intentional callback.

Very well put Ali. I remember asking friends why certain tv shows or movies nowadays are huge hits, even though I thought they were good, but nothing special. And they said it’s because they have music from the 80s, and the scenes,timelines, props are often from the 80s. They evoke a certain nostalgia that make people who grew up back then fall in love with the show/movie.

Going deeper even than nostalgia (on which our current president is basing a dangerous amount of action) I think it's significant how our adult preferences are likely influenced by what we were exposed to as children. Psychologically this is old news, but it creeps into many areas of daily life. Sometimes these can be subtle things. For example, I generally dislike and disparage the treacly art of Thomas Kinkade "Painter of Light." And yet, I'm strangely drawn to those warmly lit bungalows tucked away in the woods. I suspect this goes back to imagery from picture books and Disney movies from young childhood. Similarly, I've always suspected that my love of jazz was predisposed by the jazz-inflected music in the background of Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood. There are no "aha!" memories associated with these feelings, just an awareness of how childhood experiences lie in the subconscious.