Issue No. 26

Thank you to everyone who reached out or commented after the last issue. It was by far the most amount of reactions I’ve received to any issue so far. Founding members will all get a physical copy of the tiny book in time for the holidays. And the three paid subscribers selected at random who’ll also get one, your emails start with: tom_cun…, sooze98…, and riorid… (Substack doesn’t tell me your names, sorry). Look out for an email from me in the next few weeks asking for your mailing address.

Has the question “What should we get for dinner?” come up with a spouse or roommate or friend? Does it end well? For me, it usually goes like this:

I’m up for anything.

I’m up for anything too.

How about ramen?

Anything but ramen.

What do you feel like having?

Anything really.

When the whole universe of food options is available to us, rather than those options giving us a sense of liberty, they might leave us feeling paralyzed. Funnily enough, four very different things happened to me these past two weeks that ended up being related.

I was in the mood for baked beans one day. I went to the grocery store, and there were several different kinds up on the shelf. What should have been a quick purchase turned into a research session on my phone to see which brand was better. I eventually bought one.

Then one day someone reached out from my bank and asked if I’d consider new investment options. My current ones weren’t optimal, he said, and there were half a dozen other things we could be doing to improve returns and reduce risk. When we got down to details, those options were spelled out for me and I had to decide which ones I wanted. Another research session, this one with higher stakes. Worse, what if I regret my decision in a year, I can’t go back in time and replay a different sequence of events. So in the end, I did nothing.

Then a few days later I went to a specialist, and after doing some blood work and imaging she presented me with four options for treatment. “I don’t know, Doc.” I said. “What would you do?” She said she could walk me through the trade-offs, but ultimately, it was my choice. Ah, choice, we meet again.

Then one day, I sat down at a desk to work. I usually have 2 to 3 ideas that I’m going through in a given week, which is nice, because I can dedicate a whole day or a half a day to just one of them and not have to context switch. But that morning, I had 5 to 6 and I was adamant on making progress on all of them at the same time.

That’s when I realized that this business of having too many choices can be paralyzing. Not the business of having choices, but of having too many of them. So I headed home, disappeared under a blanket, and binge-watched Presumed Innocent and 3 Body Problem. And I did little else for the next few days except think about other things in everyday life that also make us liable to decision paralysis.

If a restaurant has a longish menu, I can imagine myself giving up and ordering whatever sounds familiar.

If I go to a store to buy a new shirt, I can imagine myself feeling frustrated and buying something that looks like my last shirt.

I wanted to buy a computer mouse the other day. There were so many to choose from that I ended up not buying anything.

Some cafes I’ve been to have up to eight different kinds of coffee beans to choose from.

My retirement plan has heaven knows how many funds on offer. Every time I log in, I feel like I’ve popped open my car’s hood (I know nothing about cars) so I just go, Uh-huh, yep, uh-huh, yeah, looks about right, good work, people. I never change any allocations.

Online shopping—hundreds of product alternatives, each with thousands of reviews, coupled with my deep-seated suspicion of products that Amazon helpfully suggests to me. It’s seldom a quick process to settle on and buy something online.

Other than the feeling of being paralyzed is the issue of satisfaction. If we’re presented with 20 choices, and we pick one, do we feel good about that choice or not really? As I was doing some research for this issue, I came across the writings of Barry Schwartz and colleagues on the paradox of choice1 and then also this talk, both of which discuss dissatisfaction as a consequence of having too many choices.

Here’s one of the studies they cite.

[In a gourmet food store,] researchers set up a display featuring a line of exotic, high-quality jams. Customers who came by could taste samples, and then were given a coupon for a dollar off if they bought a jar.

In one condition of the study, six varieties of the jam were available for tasting. In another, 24 varieties were available. In either case, the entire set of 24 varieties was available for purchase.

The large array of jams attracted more people to the table than the small array, though in both cases people tasted about the same number of jams on average.

When it came to buying, however, 30% of people exposed to the small array of jams actually bought a jar; only 3% of those exposed to the large array of jams did so.

—Doing Better but Feeling Worse: The Paradox of Choice

People who had fewer options were more likely to buy a jar of jam. Here’s another.

[In] the laboratory, college students were asked to evaluate a variety of gourmet chocolates. The students were then asked which chocolate—based on description and appearance—they would choose for themselves.

Then they tasted and rated that chocolate. Finally, in a different room, the students were offered a small box of the chocolates in lieu of cash as payment for their participation.

For one group of students, the initial array of chocolates numbered six, and for the other, it numbered 30.

The key results of this study were that the students faced with the small array were more satisfied with their tasting than those faced with the large array.

In addition, they were four times as likely to choose chocolate rather than cash as compensation for their participation.

—Doing Better but Feeling Worse: The Paradox of Choice

As the authors state, the result is counterintuitive. One would imagine that a person would be more likely to find something they like in a set of 30 rather than a set of six. But the data tells a different story.

The long and short of it is that when the burden of choice is shifted onto us, and the number of choices explodes, there is a chance that’ll end up making us feel both paralyzed and dissatisfied. The fear of missing out (FOMO) or getting wound up about opportunity costs can increase as those choices increase, making us feel bad about what could have been.

Some things that might help

Reduce your choices. One of the things I learned when I ran an agency many years ago was that clients were much happier when I gave them two design concepts to consider rather than telling them that anything and everything was possible, even though that’s true. But by artificially constraining choices, we ease decision-making, and in doing so, everyone tends to end up in a happier place.

Limit decision-making time. Determine how long you’re willing to spend researching something, and make up your mind by then. If I’m deciding on baked beans, then maybe a few minutes on my phone. If I’m deciding on which part of town to move to, then maybe the end of the month. Self-imposed deadlines keep us moving.

Figure out what’s important to you. Realize that finding the absolutely best thing is an elusive goal. And subjective. You’ll always have trade-offs, and no matter what you go for, there’ll always be something that’s better. Figure out what attributes are important to you, and decide on a thing that gives you 80% of those attributes. And learn to be content with that. Focus on the good. “Comparison is the thief of joy,” as the saying goes.2

Delegate some of the thinking about decisions. Is there a writer or an expert you trust? If you can’t make up your mind, look at what they recommend. Presumably, they’ve done the hard work of distilling many things into a short list that you can pick from. You’re in a sense outsourcing that mental burden to somebody else.

Take breaks. If you’re feeling decision fatigue, escape into something or to somewhere. I’ve had to teach myself that there’s nothing wrong with taking some time away from something to essentially take the blinders off and reset my perspective. I realize it’s a privilege and not everyone can do it. But if you can, it’s really helpful.

Realize that life’s short. Unless you’re working on something that’s mission- or safety-critical, for many of us, life’s too short to make the perfect decision every time. You make one based on the data that’s available to you, you adapt, you learn, and then you move on.

(Mrs. Doyle is suspicious of technology that promises to do everything.)

Book earrings

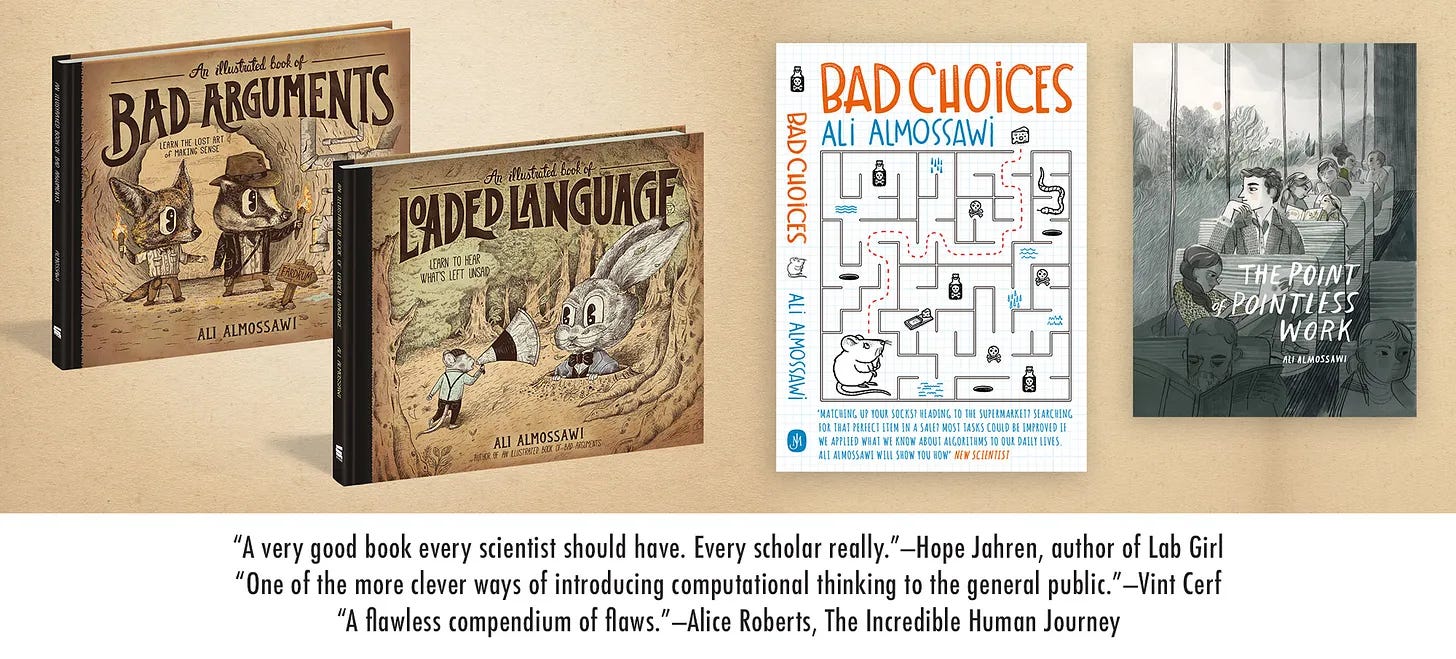

A reader challenged me (challenged me, I said!) to make an even smaller version of the book from last time. So here are earring versions of the books Bad Arguments and Loaded Language. For the sophisticated person in your life … who doesn’t mind walking around with a book hanging from their earlobes.

Larry was always full of ideas about things of which he had no experience.

―Gerald Durrell (My Family and Other Animals)

Until next time.

Be well,

Ali

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Julian-Barling/publication/232553222_Leading_Well_Transformational_Leadership_and_Well-Being/links/59f7575baca272607e2d7da9/Leading-Well-Transformational-Leadership-and-Well-Being.pdf#page=111

Attributed to Roosevelt, it seems. I always thought it was a much older proverb.