Plausible Deniability, False Causes, and Telling a Crisper Story by Reducing Detail

The trouble with saying something without actually saying it

Issue No. 4

1 Rethinking Language

Plausible deniability

(This section contains a spoiler from season 4 of Succession.) In an episode of the television show Succession, media mogul Logan Roy has just died. Two people from his inner circle are in a room, with Logan’s will and related papers in front of them. One of the two holds up a piece of paper that apparently names who ought to run the company in the event of Logan’s death. The following exchange takes place.

Frank: Hey. So, listen. In my role as executor, I’ve had passed to me a rather worrying piece of paper?

Karl: M’kay. [Looks at the paper] And … Who else knows?

Frank: As of now, so far as I know, just you and me.

Karl: So, what are you thinking?

Frank: Well, I honestly didn’t even want to start thinking till you were here.

Karl: You’re pre-thinking?

Frank: Correct.*

Karl: I mean, could it, might it just go away? I mean, it might get lost. I hope it doesn’t. But what if your hand goes a little wobbly and the draft takes it away, and it gets flushed down the toilet by mistake. I’m kidding, of course.

Frank: No, sure, you’re speculating in a comic mode.

Karl: Yeah, in a humorous vain.

Frank: Mm-hmm.

[Gerri, general counsel to the deceased, enters the room.]

Gerri: Say, what’s up boys?

Frank: Oh. Hi.

Karl: Ok, um, well …

Frank: Well, I’ve just been handed a piece of paper. It has a list of wishes, in the event of Logan’s death.

Gerri: May, I?

Karl: Mm-hmm. Paragraph three.

Gerri: And where was this found?

Frank: In his private safe.

Gerri: And this penciled addendum is what?

Frank: We haven’t touched it. The underline in the pencil is his. Undated, apparently.

Frank: Not even shared with his lawyer, or myself, so …

Gerri: So, what are you thinking?

Frank: We were joking that it could fall into the toilet.

Gerri: Yes. Well, that is a very funny joke.

Succession, Season 4, Episode 4

(* The previous two lines are in the manuscript, but not in the show’s final cut.)

That’s two dozen lines implying let’s destroy this piece of paper without actually saying so. Language is used to plant a thought without explicitly stating that thought. In the event that any of the conspirators is pressed, they’ll counter by claiming they were merely “speculating in a comic mode”. As one does. Waffling “in a humorous vain”, you might even say. The effect is that one isn’t able to constructively engage with someone who puts up such a front since their position is so malleable.

Indirections, obfuscations, euphemisms, and prevarications are all forms of vagueness that contribute to that state of malleability. They can be used to distance us from some act, either to convince ourselves that the act isn’t objectionable, or to shield us in case someone picks up on how objectionable it is. In this example, the three characters in the room know very well they’re not supposed to tamper with or destroy those documents. So they play a little game of verbal gymnastics to gauge each other’s appetite for breaking the law.

In yet another television show, the following exchange comes to mind. There too, remove is used to both shield and manipulate. For good reason from the manipulator’s perspectives no doubt, but it’s manipulation all the same. Kim and Jimmy are lawyers, and in a relationship with each other. Lying in bed one evening, Kim tells Jimmy to make sure he has all his tracks covered, as his ordeal with his brother intensifies. She implies that, but doesn’t actually say it. Not in as many words, or in hardly any words.

Jimmy: Good night.

Kim: Good night.

[Pause]

Kim: Your brother is one smart lawyer.

Jimmy: The smartest one I know. I mean, no offense.

Kim: He’d make quite an adversary.

Jimmy: You better believe it.

Kim: The kind of adversary who’d find even the smallest crack in your defense. Going against him, you’d really want to make sure you’ve got all your “i”s dotted and your “t”s crossed. Nothing for him to find.

[Jimmy immediately gets out of bed and heads to the copy store to bribe the person working there.]

Better Call Saul, Season 2, Episode 9

Here too, language is used, suggestively, to achieve an end while shielding a person from the onus of accountability. In both these examples, there’s a shorthand that the group relies on to get their thoughts across without spelling them out in words. In politics, this sort of doublespeak might be referred to as dog whistling—a politician will use coded language to compel and coral his voters to react a certain way, for or against a cause or a group, all the while maintaining plausible deniability.

Sometimes that’s achieved with subtext. Other times, there are trigger words that one can be wary of, whose purpose is take the brunt of a blow if a person is ever challenged on a position. Words like seem, and allegedly, and probably, and phrases like I believe, or I feel. When used constructively, these words and phrases couch a statement in doubt. Useful when seeking the truth. It’s the non-constructive case of deliberate obfuscation that muddies thinking.

I noted down an example of this several years ago, while reading an essay on the science of morality:

Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature … My approach is to generally make an end run around many of the views and conceptual distinctions that made academic discussions of human values so inaccessible … [T]he professional philosophers I’ve consulted seem to understand and support what I am doing.

What triggers one’s skeptical senses here is that the professional philosophers are never named. And it remains unclear whether or not those professional philosophers support the author’s approach. If one were to press that author by saying, We looked everywhere, we couldn’t find anyone, that seem gives the author room to claim an honest misunderstanding.

To counter vague language of this sort, be on the lookout for any attempts to plant some idea in your head where the idea isn’t explicitly stated. As in, where you’re maneuvered into making an implicit thing explicit. Where you feel the speaker, if pressed, would pull an expression like Paulie Walnuts’s in The Sopranos.

Emotionally charged situations are particularly amenable to this sort of manipulation, since we’re susceptible to wishful thinking in them and more willing to focus on how someone is saying something—their charisma—rather than what they’re saying.

2 Reasoning

False causes

Assuming that an event caused another, merely because the second followed the first is called the false cause fallacy. Two events may occur one after the other or together because they’re correlated in the statistical sense, by accident, or due to some other unknown event. We can’t conclude that they’re causally connected, without evidence. I rub an ointment on my forehead, and my headache goes away. Without evidence (a randomized controlled trial, say), I can’t conclude that the ointment caused the relief. What’s to say it wouldn’t have gone away anyway.

While working on a project, things might be going badly, someone from outside the team steps in, then things start going well. There might be a tendency to attribute that turnaround to the person’s involvement. Without evidence, that is as likely as the project turning around despite that person stepping in. A corollary example would be: I have a bias against John, he happens to be involved in a project that isn’t going well, I therefore determine that the project’s state is necessarily because of John. Again, without some evidence of likelihood, we can’t conclude that one thing led to the other.

I recently watched the television show The Diplomat. The story begins with an attack on a British aircraft carrier. A grainy photo shows a military boat belonging to a regional state in the vicinity of the carrier at the time of the attack, leading the US mission and their British counterparts to conclude that they’ve caught the culprit redhanded. The rest of the story revolves around a US ambassador’s work to uncover whether that’s what really happened. Which is to say, conflating association and causation takes up all of half an episode. Uncovering evidence to validate or invalidate that conflation—often the harder task—takes up the rest of the show.

From Agatha Christie to modern whodunnits, we often see a similar template applied, precisely because that head fake throws a reader off by muddying their thinking—you think you know who the killer is from the start because of some obvious association implying some definite cause. But, alas.

False causes can be especially harmful when impressed onto children. They instill in them a model of the world that’s skewed. One that breaks down the moment the child grows up a little and one day eats two chocolate bars on the same morning and isn’t then struck by lightning. Huh. Looks like dad was wrong about those two things being connected. I wonder what else he was wrong about. It’s much harder, but much more constructive, to teach them about probabilities, and about rigor, and about controlled experiments.

3 Rethinking Images

Telling a crisper story by reducing detail

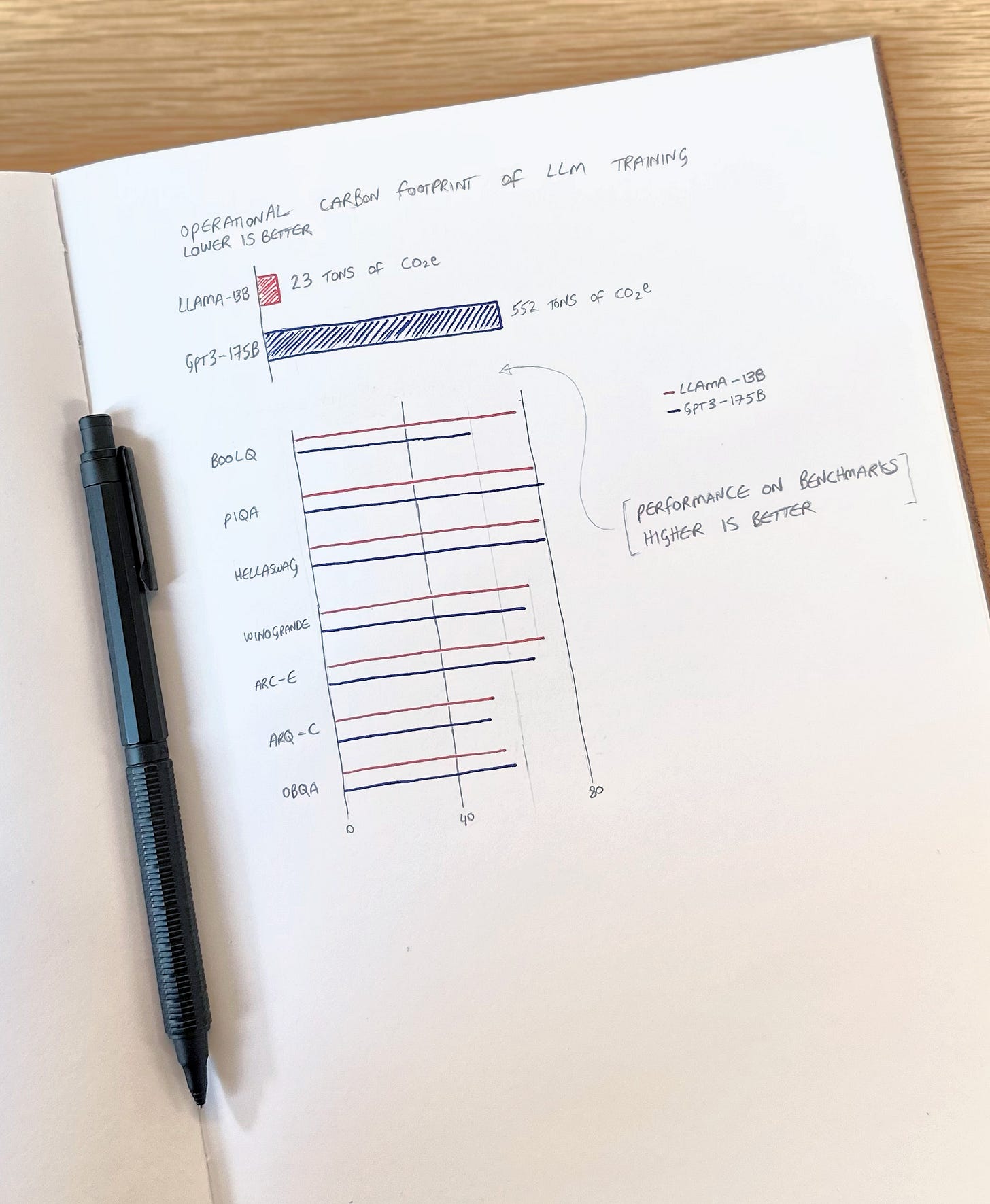

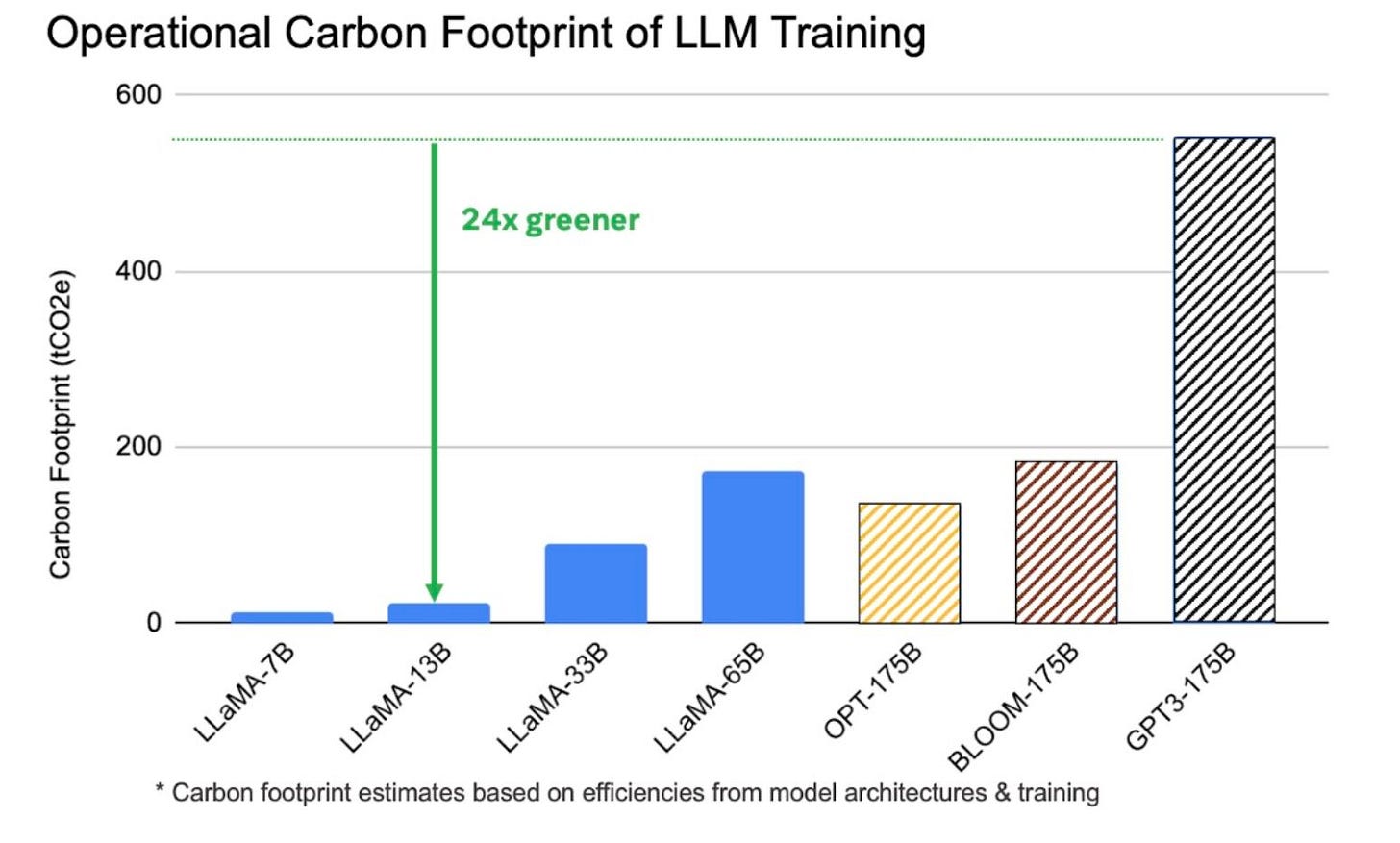

In a post comparing the energy impact of training large language models (LLMs1), we come across this graphic.

In order to make an LLM useful and usable by humans, such that it can meaningfully respond to questions, an LLM needs to be trained. And training one requires computation on physical machines that consume and produce energy. What this graphic shows is a comparison of the tons of CO2-equivalent emissions (tCO2e) necessary to train each of a series of LLMs.

From my reading of the post, I see two takeaways. Firstly, that the LLaMA-13B model, in particular, is 24 times greener than the widely known GPT3-175B model. (GPT3 is what you’ll have used if you played with ChatGPT when it first came out.) And secondly, that those two models, despite the stark difference in their environmental impact, have comparable performance when measured against a series of benchmarks.

Those two takeaways are really intriguing. I can think of two ideas to highlight them even more.

Firstly, what would be useful to see is a side-by-side comparison of tCO2e emissions for the two models in question. Showing other models is nice, for context, but they do also add noise, which in this case can be a bit distracting.

Secondly, the graphic doesn’t show me how the LLaMA-13B model is comparable to the GPT-17B model. Only the copy implies it, but the visual doesn’t show it. I have to dig into a few papers, to find this table to compare benchmarks, and then this paper, to find where the 552 tCO2e number for GPT3-175B comes from.

A suggestion to communicate both of those takeaways, visually, is to redo the graphic so that it looks like the sketch below. The top graphic now shows me that two things are very different, and the bottom graphic shows me that two things are similar. And that pair of graphics now tell the whole story.

A talent forms itself in solitude,

A character amid the stream of life …

[t]hose who don't know people fear them

And one who shuns them never truly knows them

Next time, we’ll cover converse errors, misattributing actions, and comparing shapes of lines. In case you missed the last issue, it covered availability bias, the passive voice, and representing relative magnitudes.

I hope this issue made you laugh,

—Ali

A language model tries to predict the likelihood of a sequence of words occurring in a given text. A unigram language model captures the frequency of individual words in that text. A bigram language model takes into account pairs of words and determines the frequency of their co-occurrence. This model can be used to predict the likelihood of a word following another. A trigram language model extends the bigram model by taking into account sequences of three words, allowing it to capture more complex patterns. An LLM is trained on billions of words, and can generate language in a way that closely mimics how humans communicate.