Availability Bias, The Passive Voice, and Representing Relative Magnitudes

How the ease with which we remember things can affect our decisions

Issue No. 3

1 Reasoning

Availability bias

In the television show The Bear, sous chef Sydney, hard at work on opening a new restaurant, is having dinner with her dad, Emmanuel. She shares her excitement about the prospects of this new project, but also that payroll might be a struggle for the first few months. Her dad responds.

Emmanuel: Well, I ... I can tell you’re excited and I am glad you’re excited … I want you to know that Cousin Monty always has a job for you at Boeing.

Sydney: Okay.

Emmanuel: If you decide to make a change.

Sydney: If I decide to make a change and just go like this (waves her arms around) at the airport for the rest of my life, like—

Emmanuel: Honey, honey, it’s, … It’s a different beast, that’s all I’m saying … I read about restaurants in the papers … They’re hard. And a lot of them— Yeah, a lot of them don’t work out.

Sydney: This is not last time.Emmanuel: I know it’s not last time.

Sydney: I’m in a different place in my life, in a, in a better place, I think. And I know what I’m doing. I’ve learned a lot of lessons. I’m still learning, which is actually a good thing.

—The Bear, Season 2, Episode 2

In estimating the likelihood of Sydney’s new restaurant failing, the ease with which her dad can retrieve examples of restaurants shutting down or construct likely ways a new restaurant might run out of money informs his judgment. And the ease with which Sydney can still retrieve, and mentally relive, her last failed venture, tormenting as it is, might at some point inform her decision to throw in the towel.

Decisions are driven by an estimation of likelihood—is it more likely or is it less likely that a particular judgment call is a good one. A mental shortcut that can inform that estimation is the ease with which an instance or a scenario, from a much broader set of instances or scenarios, can be brought to mind. That ease of retrieval can lead to estimations that aren’t necessarily accurate.

Sticking with food still, here’s another example. I’m at the grocery store, picking up pasta sauce. In the aisle, I find myself faced with a wall of brands. I reach for the one I remember seeing an online ad for that morning. The same one I spotted in a friend’s pantry that other time. I determine, therefore, that his brand is likely a good one.

There too, the ease with which I can retrieve some brand that’s top of mind informs my judgment about whether it’s a good brand, and therefore one I ought to buy.

If you’re estimating how many people have come down with the flu, or moved to another part of the country, or like a particular brand of pasta sauce, the ease with which you retrieve specific instances from, say, those around you can affect the conclusion you reach. When asked, “Are people moving away from the city in droves?” it’s easier to recall the faces of three friends who did.

In the seminal paper on availability,1 the following example is given. It’s a memorable study and so I’d like to share it:

Five consonants are picked for an experiment—K, L, N, R, V. All of them share the following property: a word that contains one of these letters will more likely have the letter in the third position rather than at the start of the word. Participants are told the following:

You will be given several letters of the alphabet, and you will be asked to judge whether these letters appear more often in the first or in the third position.

Out of 152 participants, 105 said the letters appeared more often in the first position.

The authors conclude:

According to our thesis, people answer such a question by comparing the availability of the two categories … It is certainly easier to think of words that start with a K than of words where K is in the third position.

This tendency is a reason why propaganda is effective. Propaganda paves that path of least resistance (easy recall) with gold, maneuvering people into taking a particular position on some topic by virtue of making that position easily retrievable. When we see an opinion constantly retweeted, reshared, amplified by hundreds of accounts, unless we know better, we may well be amenable to eventually working that opinion into our world view.

When deployed to an insidious end, that approach can manufacture consent for some otherwise unsavory condition. When deployed to a financial end, it can help sell things. Uncannily effective in the case of businesses that own multiple platforms, such as Amazon and Whole Foods (a grocery store) for instance.

You might see availability bias elsewhere in everyday life—a coach doesn’t pick a player to start in a game because they still remember that one time the player didn’t do well, or an employee is passed up for promotion because that one time they messed up on a project. You might be less likely to get on a plane if you’ve just read news of a plane accident, or to drive as fast as you normally do, if you pass by a car crash.

When we want to make a quick decision, availability can be a useful go-to heuristic, but it can also be a debilitating bias when it misrepresents the world. One idea for a fix is to take a minute to write down decisions you make where you suspect availability was a contributing factor. And to then write down why it was easy to retrieve that particular instance that informed your decision. And to then write down what other decision you might have made had you not reached for that instance.

2 Rethinking Language

The passive voice

During a daily politics show on the BBC, an interviewer grills a government minister about a security crackdown the night before. The events of the previous day were brutal, the interviewer states. Why so? His guest fidgets in his seat, visibly uncomfortable with the line of questioning. A reply follows.

Mistakes were made. We don’t tolerate human rights violations.

What’s intriguing about the minister’s response is that the passive voice is used to describe the bad thing (what was done), and the active voice is used to describe the good thing (the principle of upholding inalienable rights). This shifting of the blame may be a genuine form of dissonance on the minister’s part—people usually don’t like to be associated with heinous acts. Though it might also be a sort of maneuvering of viewers’s perceptions of what’s been lain bare.

What the passive voice excels at is this shifting of responsibility. No one ever makes a mistake, mistakes are always made. No one ever commits a crime, crimes are always committed.

On the television show Better Call Saul, a shady lawyer, Jimmy, enters an Air Force base under false pretenses. His goal is to record a TV commercial with a supposed war hero onsite. The captain of that Air Base, having eventually uncovered the ruse, pays Jimmy a visit at his law office and demands that Jimmy take down the TV commercial.

Captain Bauer: Your so-called war-hero … no such person, never was.

Jimmy: Granted, some artistic license may have been taken … I sincerely apologize for any misunderstanding … we’re just gonna have to agree to disagree.

Better Call Saul, Season 3, Episode 1

Jimmy can’t admit to committing a crime, so he leans on the passive voice to deflect. And ends by feigning objectivity with apparent neutrality with the line, let’s agree to disagree. No objectivity exists of course in the middle ground between him and captain, since Jimmy is completely in the wrong.

Prevaricating isn’t only used for distancing oneself from responsibility, but also in distancing someone else from responsibility. In a local paper, one finds the following passage:

The victim pulled over the bus to escort the males off. As the victim was escorting the males off the bus, one of the males pulled out a wooden bat and struck the victim several times, which caused the victim to be injured.

The attackers didn’t injure the bus driver. Rather, a wooden bat caused the victim to be injured.

In all these examples, what the passive voice ultimately achieves is disconnecting an action from whoever is committing it. The recipient becomes the subject of the sentence, and the actor is taken out. Whenever you come across a line that mentions an objectionable act, but leaves out who committed it, ask yourself why that is. And whether the vagueness is accidental or whether it aims to create a sort of distance between who the real actors are and the act they committed.

3 Rethinking Images

Representing relative magnitudes

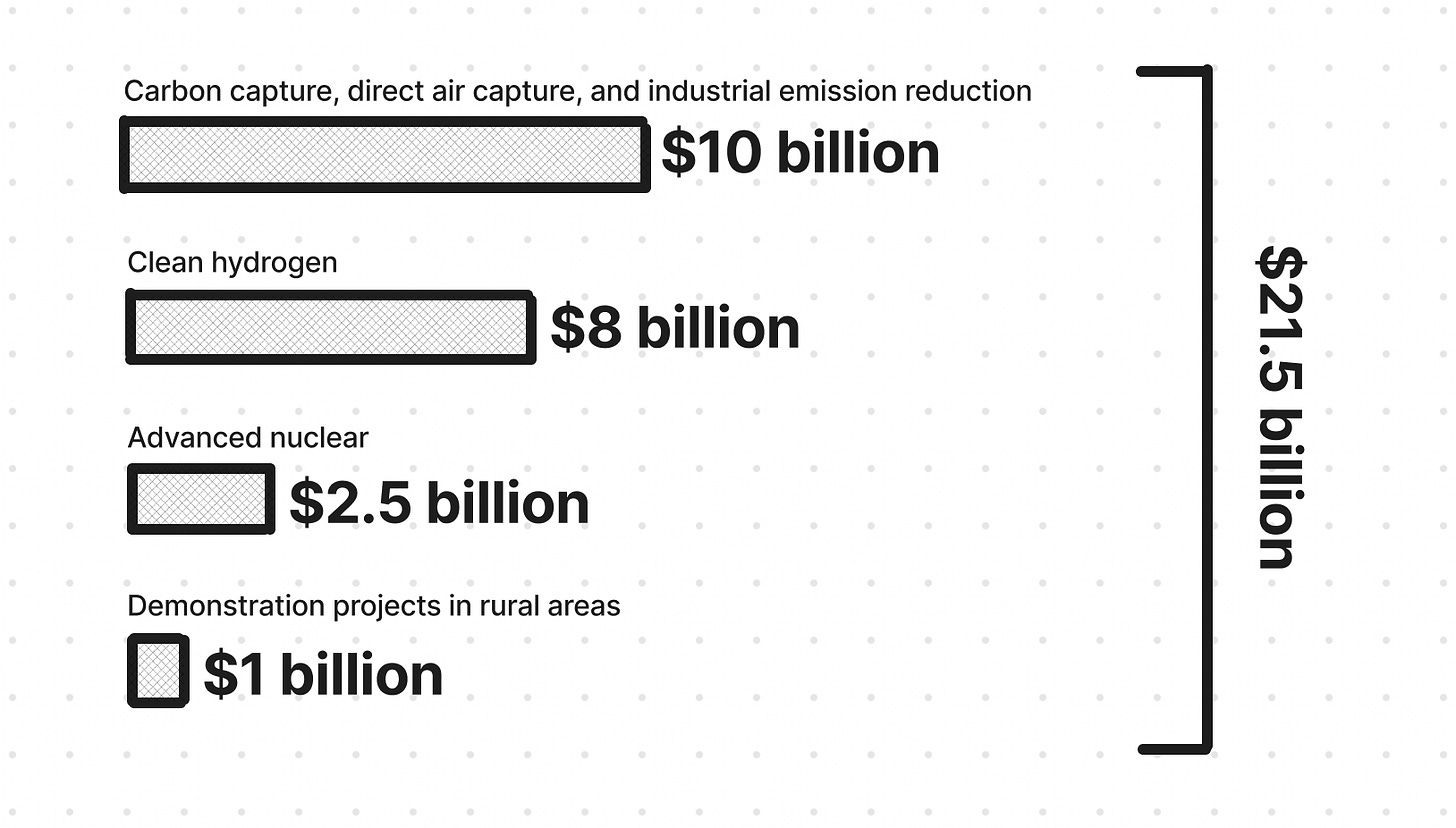

In an article about recent US legislation promising hundreds of billions in federal investments, we find this graphic. The graphic and its copy tell us that of the $550 billion spending authorized in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, $21.5 billion is for clean energy demonstrations and research hubs. Two things stand out in this graphic.

Firstly, it’s unclear whether the bubbles in blue are meant to constitute the bubble in white. Until one adds up $8 billion, $2.5 billion, $1 billion, and $10 billion, that is. Even then, one can only infer that they do. A reader looking at the graphic in passing might conclude that the amount designated for clean energy projects is $21.5 billion plus the other amounts in the blue bubbles.

Secondly, using a circle to encode data that’s meant to be amenable to comparisons can make it difficult to reason about relative magnitudes. Comparing two lines is intuitive—we can determine which is bigger by a bit, which is bigger by a lot, which is double the size of which, and so on. Not so with circles. In this case, and at a glance, $1 billion and $2.5 billion look fairly similar.

One idea to make this graphic clearer would be to redraw it like the following sketch.

You can know the name of that bird in all the languages of the world, but when you’re finished, you’ll know absolutely nothing about the bird. So let’s look at the bird and see what it’s doing—that’s what counts. I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something.

—Richard P. Feynman (What Do You Care What Other People Think?)*

Next time, we’ll cover false causes, plausible deniability, and telling a crisper story by reducing detail. In case you missed the last issue, it covered survivorship bias, “people are saying”, and making a blood pressure graph more readable.

Until then,

—Ali

* Watching Oppenheimer this past weekend got me rereading the three Feynman books on my shelf—his two memoirs and his letters. They’re among the few books I bought in my early twenties that I still hold onto. The very best companions in that period of one’s life when you’re liable to start every other sentence with the phrase, When I grow up, I want to ...

Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability, people.umass.edu