False Dilemmas, Macroeconomic Conditions, and Visualizing Distributions

New in this issue: A musical short on critical thinking, starring animals.

Issue No. 6

When I was in school, in the ‘90s, I had two favorite magazines. One was called Buster1 and the other was called Quiz Kids.2 Both now defunct. The best part about them is they came with a free gift. Really exciting. In my teens, the magazines I bought came with CDs loaded with software, mostly available online, mind you. But it sure felt good to crack open a CD case every month and wonder what was inside.

I wanted to recreate that feeling with a little addition to this newsletter. Over the summer, I’ve been playing with the idea of taking bite-sized explanations of logical errors, casting them as rhyming verses, and setting the verses to music. I hope you enjoy these videos. This first one is on false dilemmas.

(In that same spirit, starting next time, I’ll be narrating every issue. Narrations will be accessible to paid subscribers, and will include the occasional improvised content or thought. Thank you very much for your continued support.)

1 Reasoning

False dilemmas

Decisions can be difficult, they can be nuanced, and often there are competing factors to consider. A false dilemma attempts to simplify decisions by simplifying the world around us. It splits the world into two—usually, two—categories and we’re asked to pick one category or the other. What makes it false is its oversimplification of the world, which ends up concealing necessary detail and restricting our thinking.

For instance, a supervisor tells a worker that they can either be, A, assertive and therefore strong, or, B, empathetic and therefore weak. A person is constrained to one of two options, and an impressionable or an obsequious worker might not have the presence of mind to push back on that categorization. In reality, a person can be both assertive and empathetic. False dilemmas restrict our thinking because they make us assume that only two options are on offer when there might well be others.

In a speech on the artist’s struggle for integrity—one of my absolute favorite speeches—we hear the following passage,

The world you first encountered when you were fifteen, the world which starved you, comes back. This time it is bearing gifts. The phone didn’t ring before, if you had a phone. Now it never stops ringing. And you become, or you could become, a very important person. Here, you are again … and you must decide, all over again, whether you want to be famous, or whether you want to write. And the two things, despite all the evidence, have nothing whatever in common.

—Jimmy Baldwin, The Artist’s Struggle For Integrity

When I first read that line, I was very young. And it affected me the way either-or models of the world often affect us—they propel us in one direction because of how absolute they sound. I want to have integrity, I’d decided. Therefore, I have to work in obscurity. What I hadn’t realized in the midst of that idealism is that there is a third option—a person can have integrity and their work can bring them renown.

Baldwin might have meant the sentiment hyperbolically, to make the point that a person has to, above all else, stay honest in whatever it is they’re doing. And that any other benefits that come a person’s way are merely incidental. But we read people we adore, and we follow speakers we idolize, and we vote for politicians we believe in, which is why we can be so amenable to their categorizations of the world, even when they are hyperbolic.

On an episode of a television show about the afterlife, the protagonist—Eleanor—has made it to the good place due to a clerical error by its architect, Michael. Michael messed up. She’s trying to figure out a way to save herself and avoid getting Michael thrown into the bad place. While she’s in a heated debate with her assigned soulmate Chidi, who knows the truth about her, the following exchange takes place:

Eleanor: Why do bad things always happen to mediocre people … who are lying about their identities?

Chidi: Okay, you have two options. You can confess and save Michael, or you can continue to lie and condemn him to an eternity of unimaginable pain.

Eleanor: Or Option C. Continue to lie about myself and find a way to save Michael. Can we somehow throw Tahani under the bus?

Chidi: No, there’s no way to stop this except confessing. Any moment now, Michael is going to get on that train, and we will never see him again.

—The Good Place, Season 1, Episode 7

While Eleanor is wrong about a lot of things, she does make a good point here. That that there are more than two options to getting out of the problem she’s in.

And a final example. I recently came across the following post online:

I’m so glad the Metaverse hype is over. All those Metaverse experts have moved to AI or whatever, while companies like [mine] are investing billions to generate actual value. The future is bright for those who build and not just talk.

Regardless of what one thinks of the latest wave of technological discourse, what the argument here tells us is that the world has two types of people. People who chase fads and don’t build, and people rooted in established industries who build. There is of course a third type—people who chase fads and build. And a fourth type—people who invest in traditional industries at established companies and don’t build. And so on.

To protect yourself from false dilemmas, tune your ears to any argument that casts the world as an either-or. Either we do this or that will inevitably happen. Either you’re with us, or you’re with our enemies. And ask whether a line like that is constraining your worldview on purpose in order to conceal something.

(Have you encountered a false dilemma in a negotiation? If so, how did that go? They can be common there too, to direct the conversation to where one party wants it to go.)

2 Rethinking Language

Macroeconomic conditions

Layoffs have hit the tech industry to the tune of nearly 400,000 workers in the past two years.3 Earlier in the year, at its peak, I’d often read in US press releases some mention of “challenging macroeconomic conditions” as the reason behind the decision to let workers go. In economic terms, a macroeconomic condition can mean something like an increase in the average cost of goods and services (inflation), brought about by things like political uncertainty or a global pandemic.

When used, precisely, the phrase connects a cause, such as a global trend, to a familiar effect, like a decision to reduce staffing. When used, imprecisely, however, it becomes a red herring (a distraction), to justify the same effect while obfuscating the real cause. For instance, a company might have let workers go due to its own mismanagement rather than an environmental condition that was out of its control. You might hear euphemisms of that sort any time there’s a need to mask unpleasant news or incompetence.

Another one I’ve come across in local news is externalities. When used precisely, the word can be true to its definition—unanticipated consequences of some economic activity that aren’t reflected in the cost of the goods or services involved. When used imprecisely, it becomes an elusive, abstract euphemism to explain why, say, a project is behind schedule—the project is being behind schedule not because city officials didn’t step up, but because of externalities.

If a word or phrase sounds ambiguous, define it, break out its parts, and then consider whether whatever’s being attributed to it is supported by evidence.

3 Rethinking Images

The value of showing a distribution rather than just a single number

Averages summarize information. Distributions spell them out. Distributions annotated with summaries are one of my favorite ways of telling a story. And I’d like to share one way of doing that with a type of plot called a beeswarm plot.

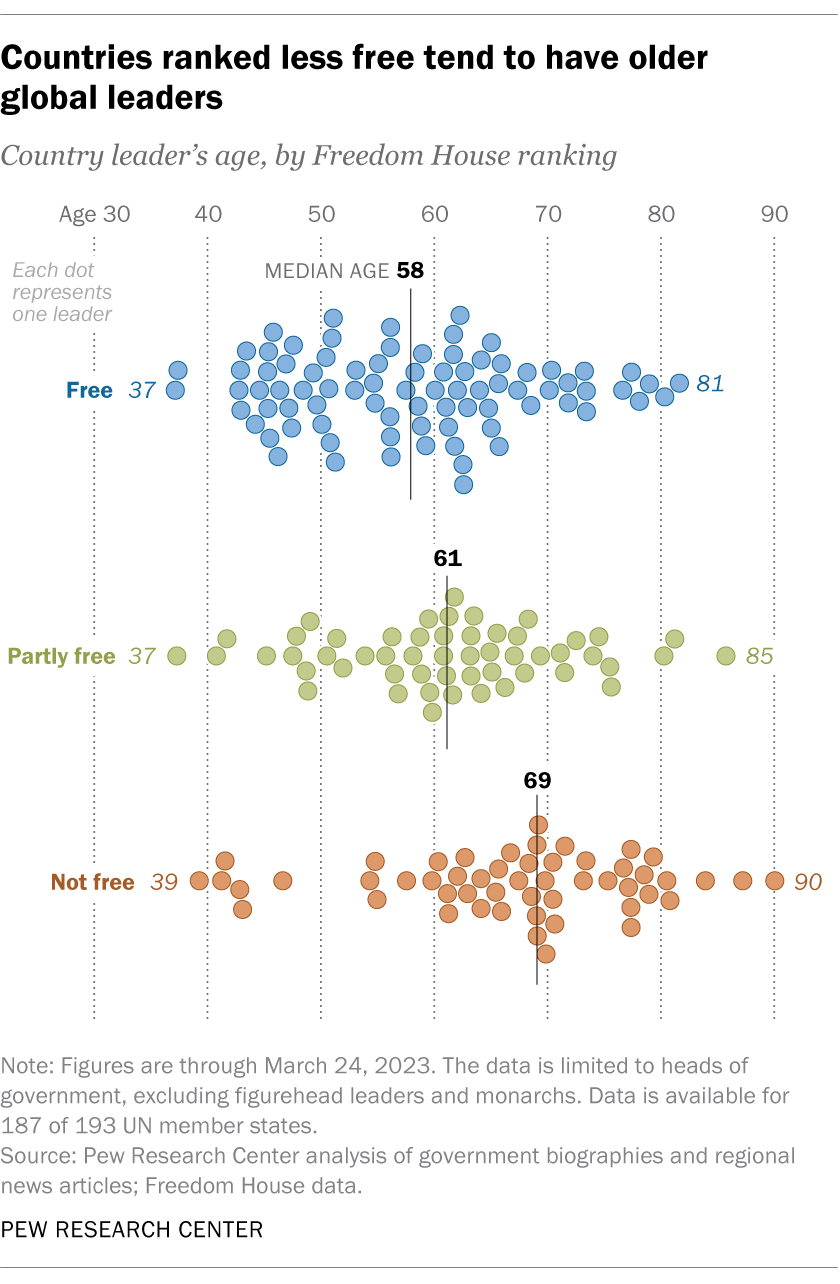

In an article about the ages of world leaders, we find the graphic above. It shows us three plots4 of leaders’s ages, split by whether their country is free, partly free, or not free. We’re shown the median age for each of those groups and a distribution of ages along a horizontal axis. You can tell right away where there are more of a thing and where there are less of it. These plots are excellent because they’re a compact way of telling multiple stories.

Firstly, we can tell that countries classified as free have had nearly twice as many leaders as countries classified as not free. Not surprising, considering that leaders in the former type have terms and term limits. Still, what a nice way to communicate that information at a glance, and a good way to provide context for the medians computed for each group—more dots buzz around the median in countries classified as free than in countries classified as not free.

Secondly, we see that the median age for leaders goes up the less free it is. Countries classified as free tend to have younger leaders, and countries classified as not free tend to have older ones. Again, not surprising, considering that biology is the determining factor for when a leader’s term ends and another’s begins in countries that aren’t free.

Thirdly, the dots at the ends of each swarm are intriguing. Particularly, for countries classified as free. The accompanying article tells us that the “United States is one of only two countries that are classified as free and have a leader in their 80s or older.” This insight can lead to—hopefully, constructive—discussions about what factors lead to a US president being more than twice the age of the average resident. (The average US resident being 38 years old.)

This article could have given us three numbers—the medians of each of the three groups—and called it a day. But by showing the distributions from which each of those numbers is computed, it’s able to tell additional stories.

[M]ay you be forever blessed for that moment of bliss and happiness which you gave to another lonely and grateful heart. Isn’t such a moment sufficient for the whole of one’s life?

—Fyodor Dostoevsky (White Nights and Other Stories)

Next time, we’ll cover slippery slopes, “it’s complicated”, and the trouble with infographics. In case you missed the previous issue, it covered converse errors in reasoning, how newspaper headlines misattribute actions, and comparing shapes of lines in visualizations.

Until then,

—Ali

Beeswarm plots are insightful, and they look great too. Imagine how you’d use them to visualize subway usage—more swarms in the mornings and afternoons. Or to visualize restaurant visits—more swarms around lunch and dinner time. Or to visualize logins to some channel or network from a distributed team—more swarms around mornings in various timezones.