Converse Errors, Misattributing Actions, and Comparing Shapes of Lines

The fairly common mistake of conflating cause and effect

Issue No. 5

A packed issue this Thursday. I’m excited to bring you the very first reader spotlight. These informal, one-on-one chats are a reward you can unlock by referring friends to the newsletter. My heartfelt thanks to

for spreading the word about it, far and wide. It was a joy chatting about seeing things in a new light, engaging with the world in a rational way, stories that made us cry, and other topics. Click the button to read the supplement.1 Reasoning

Converse errors

The converse error assumes that if a statement is true, then it’s converse must also be true. To give an example of what that means, take this line, from the very end of an essay on a writer’s place in society:

Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced.

—Jimmy Baldwin (As Much Truth as One Can Bear)

Something that’s faced (A), the line tells us, might:

→ Change (B)

→ Not change (C)

→ Become harder to change (D)

→ Become easier to change (E)

B can’t happen unless A happens. But when A happens, it won’t necessarily lead to B. It might. But it might also lead to C, or D, or E. Assuming that A necessarily leads to B would be committing the converse error.

Self-diagnosing a health condition can be prone to that error in thinking. We might jump from a symptom we’re experiencing, like a throbbing in our head, to a catastrophic disease, not realizing that many other diseases (or no disease) may be associated with that symptom. And not necessarily the one some website directed us to. In other words, a catastrophic disease can’t happen unless the throbbing is present. But a throbbing being present doesn’t necessarily imply the catastrophic disease.

One practical realization from knowing about the converse error is in how we encourage someone to do something. Do we focus on the effect or do we focus on the cause. Does one teach a group of students wanting to become entrepreneurs that disruption—an upstart moving into a market and displacing an established business—is the only path to innovation? A refrain that’s often heard. Or does one instead teach that there are other ways to innovate, like creating brand new markets that don’t destroy existing ones. The way Square did when it allowed micro businesses and independent contractors to accept credit card payments through their mobile phones.1

Here are two more examples of the converse error from recent television shows I’ve been watching.

On an episode of Hijack, the protagonist, Sam, played by Idris Elba, is working out whether the hijackers on the plane, having just fired a shot, are carrying live bullets. The passenger sitting next to him has a theory that the guns are fakes. He decides to relay a message scribbled on a napkin to the passengers seated in the cabin behind them. The message reads,

Check floor for bullet. [If no] bullet, turn on reading [light.]

Someone spots the scrunched up napkin on the floor, picks it up, reads the message, and has a look around on the floor for bullets. She then turns on her reading light. The following exchange takes place between Sam and his neighbor.

Sam: It’s not enough.

Passenger: Reading light means no bullet. No bullet means blanks.

Sam: Or it means they couldn’t find a bullet.

Passenger: We could end this.

Sam: Or we could get a lot of people killed.

—Hijack, Season 1, Episode 3

As with the earlier examples, if firing a blank means no shells fall to the ground, not finding shells on the ground doesn’t mean the hijackers’s guns are loaded with blanks. They might be, but it might also be the case that some are loaded with blanks and others are loaded with live bullets. Or, as Sam correctly deduces, a bullet may have fallen to the ground, but the passenger who looked for it wasn’t able to find it. There could be all sorts of reasons.

On an episode of The Afterparty, a groom is found murdered the morning after his wedding. The groom’s mom, Isabel, determines that he must have been poisoned with the poisonous flower plant, the Devil's Trumpet. She walks into the bride’s parents’s room and finds it full of Devil’s Trumpets. Aha! The murderer has been caught redhanded. She calls everyone in and the following exchange takes place.

Isabel: Everybody in. Come on, I have something to show you.

The bride: Are those my centerpieces?

Isabel: That’s proof. Proof that [the bride] killed my boy. And [her parents] supplied the poison. Why else would they have all of these flowers?

The bride’s dad: There’s a perfectly good explanation … if you just let us speak!

The bride: You only think this proves something because you don’t know our mom … you see, she only gathered all the centerpieces ‘cause she didn’t wanna waste them.

The mom: Frugality is a virtue.

Isabel: You’re just the definition of prudence. So, should I hide the silverware?

—The Afterparty, Season 2, Episode 5

To protect yourself against converse errors, always ask yourself if the one cause for some effect is likely to be the sole cause of it, or if there could be others. Play out the thought experiment.

(Converse errors work well as a dramatic device. Can you think of any scenes in movies or television shows where you’ve seen them?)

2 Rethinking Language

Misattributing actions

The last two issues covered the passive voice and plausible deniability, two ways that vagueness can be injected into language. Recall that the passive voice assigns an action to an unknown actor and makes the recipient the subject of the sentence. For instance, a newspaper known for slandering a book’s protagonist, Harry, publishes a piece distancing itself from that act.

“Yes, they’re very complimentary about you now, Harry,” said Hermione, now scanning down the article. “‘A lone voice of truth … perceived as unbalanced, yet never wavered in his story … forced to bear ridicule and slander …’ Hmmm,” said Hermione, frowning, “I notice they don’t mention the fact that it was them doing all the ridiculing and slandering though.”

—Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix

What misattributing actions does is slightly different. It assigns an action to the wrong actor, giving agency in some cases to inanimate objects. We might do it to obfuscate and misdirect, or in order to soften the impact of some news being conveyed.

In a post from a broadsheet journalist, we find the following line,

Our final wrap of today’s events, which left 20 missing.

The line tells us what happened, but it doesn’t tell us who did what. The day’s events certainly didn’t leave 20 missing. So, one might ask, who did? No doubt a human actor. What the misattribution achieves, irrespective of the editor’s intent, is both the effects we just mentioned—it misdirects and takes the edge off the unpleasant news.

I was reading a profile of a public figure’s personal friend not too long ago, published in New York Magazine. An excerpt from her autobiography was quoted in the piece, where she discussed a ceremony she had planned for a divisive person. The excerpt included the following line.

I’d found myself . . . planning the most divisive [ceremony] in American history.

This one is a bit more subtle. The author splits themselves into two—one part has agency and the other doesn’t. The part that has agency finds the part that doesn’t have agency planning the divisive event. It catches it in the act.

The comedian Brian Regan, whose work I adore, has a bit about lazy writing that’s relevant. In one of his comedy specials, he deconstructs the phrase “One thing led to another” and applies it, absurdly, to a series of events beginning with an art school rejection and ending with the atomic bomb being dropped. No actors can be found in a line like that—things merely lead to other things.

Be on the lookout for misattributed actions by spotting ambiguous language that either gives agency to something inanimate—a day, an event, a projectile, a fist—or takes agency away from someone—we had to do it, we had no choice, you see.

(Any other examples of misattributed actions come to mind from a news headline or an article?)

3 Rethinking Images

Comparing shapes of lines

In an article about the social media sites American adults regularly get their news from, we find this graphic. The graphic uses a line’s shape to encode whether something got better or worse. As a reader, I can immediately use that approximation to get a yes or no answer to a question. Are American adults getting more of their news from this particular site? The line’s going up. Yes. Detail—history—is traded for immediate, instinctive clarity.

In this example, we have the added decision of placing a set of lines beside each other, and having them span the same range (the years 2020, 2021, and 2022). Comparing these lines is now much easier than if they were plotted in the same view, which is to say, made to share the same axes, given different colors, and overlapped.

Another decision made here that’s excellent is maintaining the significance of the y-axis while not showing its labels. By hiding that detail, but keeping the scale, I can now not only answer the graphic’s main question (are American adults getting more of their news from each of these sites?), but also an added question (how do users across these sites compare, relative to each other?) That lets me see three distinct types of users: the three leftmost ones, the three middle ones, and the four rightmost ones.

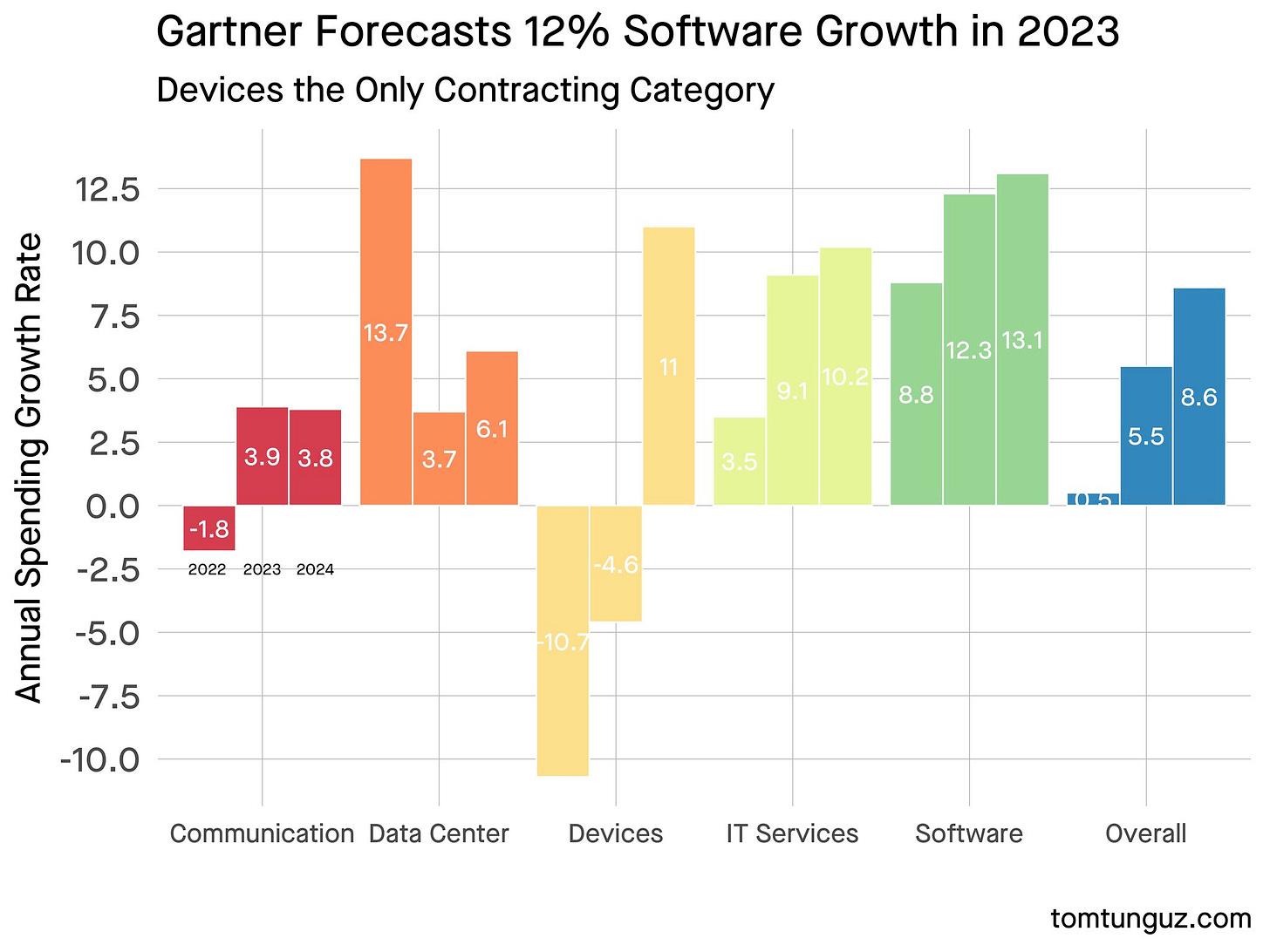

I applied the same approach to another graphic I came across recently, showing the growth rate in annual spending in the technology sector.

Using the same approach to communicating the story’s main takeaway, and abstracting away detail like colors and tick lines, we end up with a graphic that is simpler and easier to interpret.

Chance does not bestow any of her blessings on him. But chance is unpredictable, one must give chance time. For the day when chance will at last smile on him he can only wait in readiness.

—J. M. Coetzee (Youth)

Next time, we’ll cover false dilemmas, “macroeconomic conditions”, and the value of graphing a distribution rather than a single number. In case you missed the last issue, it was on plausible deniability in language, the false cause fallacy, and how to redesign a visualization on LLMs to tell a crisper story.

Until then,

—Ali

P.S. Here’s one last example of the converse error from a Key & Peel sketch: youtu.be/xU1gjhY6cKo (contains strong language)—genetics can lead to similar mannerisms, but similar mannerisms don’t necessarily mean two people are related.

You might want to listen to this episode from HBR IdeaCast for more on non-destructive creation: Disruption Isn’t the Only Path to Innovation

Converse Errors reminded me of math analysis, necessary and sufficient conditions proving a conjecture. In the field of Control Theory, which is what I studied, I remember seeing more proofs around linear time-invariant systems employing both necessary and sufficient conditions. Proofs around nonlinear systems, however, that could muster more than just sufficient conditions were nonexistent. My peers and I always related that observation back to how much better we were able to design controllers in the context of the former. The toolbox was just bigger. Which is likely why my favorite professor used to say “the best Control Engineers design their Plants” (i.e. the system to be controlled, versus the controller, which is what we trained on designing)