Survivorship Bias, People are Saying, and Making a Blood Pressure Graph More Readable

A newsletter for curious minds

Issue No. 2

It’s been lovely reconnecting with many of you these past couple of weeks. I’m grateful for your emails, and grateful for the support you’ve shown this still nascent little project.

Kevin Kelly was in town the other day promoting his latest book. It was my second time listening to him in person. Chief among the notes I brought to the dinner table that evening was the line, Don’t be the best, be the only. A sentiment I like a lot, and that I first heard a variation of from a standup comic in London.

Sitting across the dinner table from me, my daughter asked, “But what does that mean?” What does that mean, I thought. I cast my mind to a book we’d once talked about. “Remember that passage in James Dyson’s autobiography,” I said. “Where he discovers that an excellent way of improving his stamina is running up and down the sand dunes in Norfolk? Everyone else was running circles on the track by day, but he was the only one going up and down the dunes by night.” A tiny innovation that differentiated him from everybody else and in doing so gave him an edge.

Differentiation has in my mind always meant tapping into that side of us that’s a bit odd, that’s a bit quirky, a bit stubborn. A bit hard to articulate at a social event when someone asks, “And what is it that you do again?” Best accentuated and developed through some sort of discipline where you can revisit it with regularity and without the pressure of judgment or expectation. I’ve found it immeasurably helpful, for instance, to work that discipline into a daily routine and to attach a tiny, tangible, immediate reward to it. I go to a cafe early every morning. The reward is the drink. And the one hour I spend there, I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

P.S. On the books front, Bad Arguments is now available in Romanian in print, and in Ukrainian online.

P.P.S. Substack has rolled out a new rewards program. Readers can unlock up to three rewards for referring friends to the newsletter. The first two rewards unlock a complimentary paid subscription, which will get you benefits including an acknowledgment in my next book. For the third reward, I thought an interview might be fun—I interview you, that is, and then publish our chat in an upcoming issue. If you have other ideas, about this or anything else, let me know in the comments.

1 Reasoning

Survivorship bias

“Hey, mister, who’s going to win the next election?” a little boy asked me at the park the other day. He must have been four or five. I was on a bench, magazine spread resting in my lap. “No idea,” I told him, but I sure knew someone who did. I pointed to a photo in the magazine spread. “This guy right here has accurately predicted the outcome of the last three elections. He says the next one will be won by the tall guy.” And with that, the boy waddled down the pathway to her parents. A little more enlightened.

What this made-up story demonstrates is survivorship bias. The tendency to draw conclusions from the slice of things that are still around, while ignoring those slices that aren’t. In this example, when deciding whether to put one’s trust in the predictive ability of a person, one might be tempted to look at that person’s record of accurate predictions, and perhaps ignore their record of inaccurate ones.

Headlines can be complicit in exacerbating this effect. In an article from not too long ago, an investor, hot on the heels of predicting the market crash of the year 2000, warns of an impending and ominous crash in 2023. Headlines like that pop up every now and again. It’s hard to keep track of which person said what, and how often they were wrong about a prediction. It makes for a catchier headline to only remember the times a person predicted something correctly.

The effect can lead to misinformation. As in an episode of a TV show covering the history of in vitro fertilization (IVF), where a US senator shares an observation on the risks posed by an unregulated industry. There, some clinics chose to pick and chose which data to share with patients:

[These clinics are] more likely to, for example, quote national success rates rather than clinic-specific success rates. They’re more likely to talk about pregnancies but not miscarriages.

—US Senator Ron Wyden, History 101, Season 2, Episode 9

And as in an episode of a TV show, where the seeds for a different form of misinformation are planted. There, a father successfully strikes an arrow through an apple balanced on his son’s head—an expert marksman, it would appear. The crowd is ecstatic. Only for the camera to zoom out and reveal the poor boy’s body chock-full of missed arrows from previous attempts.1

Survivorship bias can also be seen in feel-good stories we share about sports heroes or celebrities, whose path to stardom can sometimes be pictured as inevitable. The odds of becoming a gold medalist at the Olympics are minuscule—those who make it have no doubt beat the odds and achieved something extraordinary. The stories that aren’t often told, however, are those of everyone who puts in the same effort, but never makes it themselves, likely due to other factors. Those are the stories of people who spend a lifetime “digging a dry hole”, as economist John List phrases it.2

To protect yourself against survivorship bias, it’s useful to think in terms of sets. What set does the thing you’re dealing with belong to? People who can predict election results. What’s the subset you’re focused on? People who have correctly predicted the last three election results. What other set—out of several—does that leave? People who have predicted the last three election results, correctly, as well as other election results, incorrectly.

(A question to ponder: Is a résumé an example of survivorship bias?)

2 Rethinking Language

People are saying

It’s tempting to take the opinion of one person and turn it into a statement of reality. You might have the TV turned to the news. A reporter will be at the site of a car crash and go, “Witnesses at the scene are saying there was ‘a scuffle followed by a loud bang.’” They’ll then cut to one witness, “I heard a scuffle followed by a loud bang.” Cut back to the reporter. “And there you have it, folks. Over to you in the studio.”

In this example, one witness’s testimony is turned into the testimony of a collective of witnesses. That in turn is meant to lend authority to the opinion being pushed, which in this case is how the car crash occurred. It doesn’t have to be malicious, of course. It may well be unintended—a way of convincing ourselves that our conclusion rests on solid footing. Either way, extrapolating from a single data point creates a skewed model of reality.

Whenever a group is used to justify some narrative or position, break that group apart. Ask for specific names, look into what they actually said. And even then, discuss the merits of the issue, since a phrase like, “People are saying”, can and often is used as an appeal to a sort of vague authority. One might find that same appeal in lines like, The experts said such and such. That, rather than saying, That particular person said such and such.

3 Rethinking Images

Improving a graph’s readability

In a recent issue of the excellent

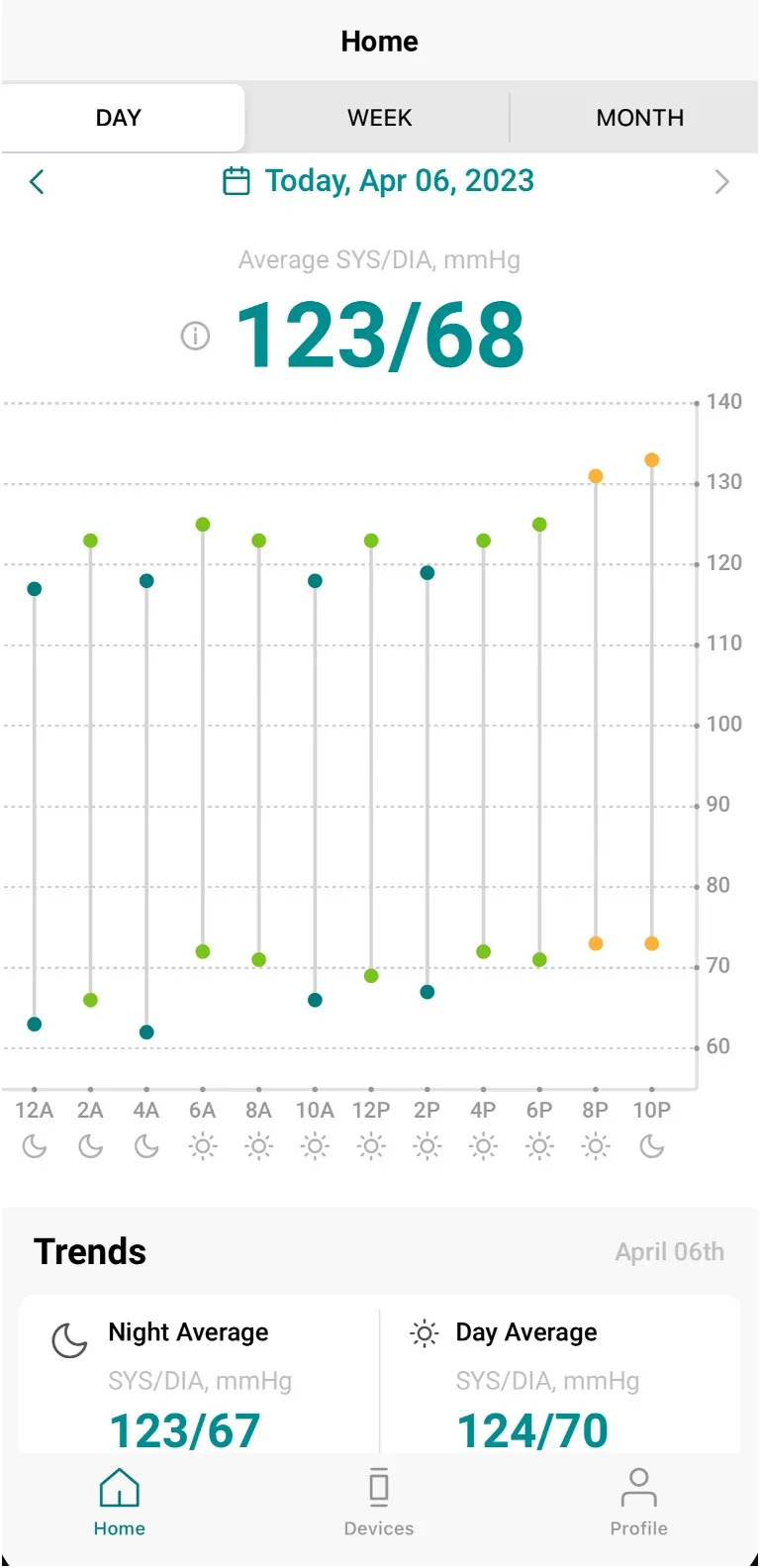

, I read an intriguing review of a continual blood pressure bracelet, not yet available for the US market. In that review, we find the following screenshot of the bracelet’s app, showing 12 blood pressure readings over the course of one day.

In a blood pressure reading, the top number indicates the maximum pressure the heart exerts while beating and the bottom number indicates the amount of pressure in the arteries between beats.3

Generally, a blood pressure reading that has either the top number above 120 mmHg or the bottom number above 80 mmHg is considered elevated. So if I’m looking at a series of readings, what I might be primarily looking for are those particular cases where my readings are elevated. And then also, I might be interested in seeing whether my elevated readings are becoming more or less frequent.

When I look at the graphic in the screenshot, two things stand out.

Firstly, every reading has a vertical line connecting its top and bottom numbers. If I—a regular user of the app, as opposed to a physician—want to know which of the readings are elevated, I wouldn’t look to the lines, which are somewhat distracting, but instead to the color-coded circles at the start and end of each line.

Secondly, decoding a circle’s color without a legend is doable, but it requires work on the reader's part—teal means not elevated, green means one number is elevated, and yellow means both numbers are elevated. If I’m worried about hypertension, then what I'm actually looking for are readings that have yellow circles. If I were colorblind, I might have not been able to figure that out by looking at the circles, and would have had to use my finger to trace each circle to the corresponding tick on the y-axis.4

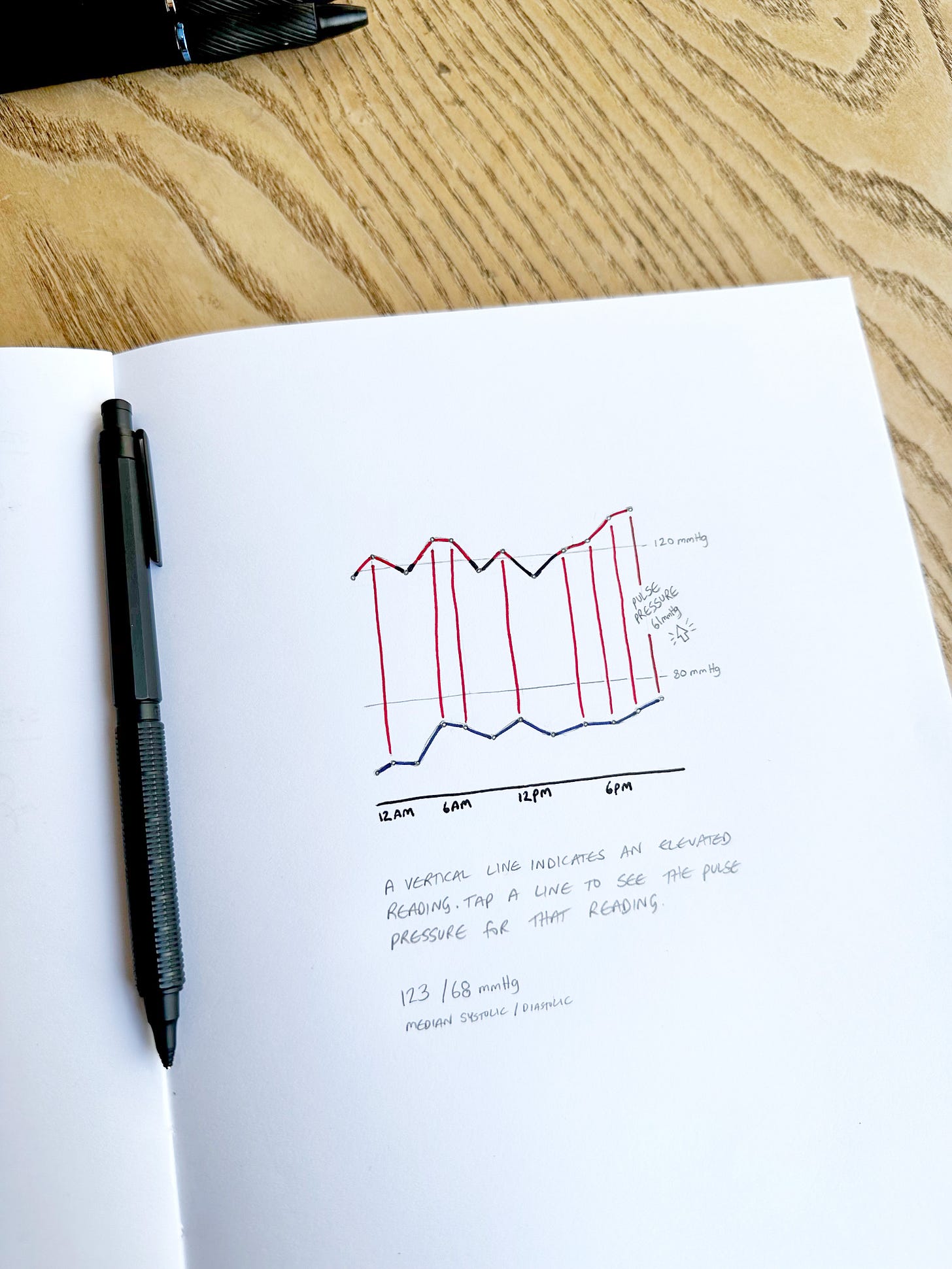

One idea to improve readability is to redo the graphic so that it’s immediately apparent which readings are elevated, by only showing lines for those readings.

A measurable variable like blood pressure feels like it’s more amenable to a line, which is why the reworked graphic shows each of the top and bottom numbers as lines. In cases where a line segment goes above the normal range, that segment shows up in red. What’s also apparent now is that many times, there are elevated readings in cases where one of the two numbers is within range (as in, blue). This was a bit more concealed in the original graphic.

I can now see, at a glance, that my bottom number is always within the normal range, that my top number jumps over and under the normal range, and that more than half of my readings are elevated.

I come from a line of children without end.

—J. M. Coetzee (Life & Times of Michael K)

Thinking Questions From Last Time

Issue No. 1 asked if you could think of an example where confirmation bias is a useful instinct. I’ve found it to be useful when I’m in the middle of a nascent project that’s taking shape. Being hyper-focused on a topic means I start seeing it everywhere. That’s not to say it actually exists everywhere, and all the time, but my elevated sensitivity helps me now see it. The risk of this hyper-focus, of course, is that selective anecdotes can give the illusion that one’s experience or advice is supported by sufficient evidence when it may not be.

Another example comes from a passage I recently stumbled on5 about Nintendo’s Shigeru Miyamoto, the renowned video game designer.

Miyamoto, and Nintendo as a whole, do not use focus groups. Instead, Miyamoto figures out if a game is fun for himself. He says that if he enjoys it, others will too. He elaborates, citing the conception of the Pokémon series as an example, “And that's the point – Not to make something sell, something very popular, but to love something, and make something that we creators can love.

Reading that, I conclude one of two things is likely true. Either development at Nintendo is truly as Miyamoto describes it—projects that are labors of love, that then happen to be commercially successful—or, more likely, that Nintendo has such a hold on culture, that they’re tastemakers. In which case, it’s not unreasonable to be inward-facing with design decisions, knowing that paying customers are more than willing to put their faith in your ability to know what they ought to be plugged into.

Issue No. 1 also asked if you could identify examples of feel-good associations in a speech by a favorite speaker or writer. I’d like to share one I like a lot.

The other day, suddenly, out of the blue, while we were talking about something completely different, my partner Dorothy burst out as follows: “On the other hand,” she said, “on the other hand, how proud your mother would have been! What a pity she isn’t still alive! And your father too! How proud they would have been of you!”

Dorothy was right. My mother would have been bursting with pride. My son the Nobel Prize winner. And for whom, anyway, do we do the things that lead to Nobel Prizes if not for our mothers?

“Mommy, Mommy, I won a prize!”

“That’s wonderful, my dear. Now eat your carrots before they get cold.”

Why must our mothers be ninety-nine and long in the grave before we can come running home with the prize that will make up for all the trouble we have been to them?

—J. M. Coetzee, from a speech at the Nobel Banquet in December 20036

While on its surface, the passage might feel melancholic, the key takeaway for me is the association between an outcome (winning a prize) and it being conveyed as worthy only insofar as it fulfills an unfulfillable transaction between parent and child. The speaker here doesn’t aim to persuade, but to instead connect an unworldly quality with a worldly reward, and in doing so, elevate it.

Next time, we’ll cover availability bias, the passive voice, and representing relative magnitudes. In case you missed it, the previous issue covered confirmation bias, “we’re like a family”, and overloading symbols and colors.

Until then,

—Ali

Browser extensions like Colorblindly can help you simulate color blindness on a webpage.

I often use this logic with horror movie characters so I don’t get frustrated with their choice of actions. I tell myself there were 99 other versions where the main character didn’t “go on that trip” or “open that door for a stranger”, and they just lived normal lives. The one person that did, had a more interesting story and so the movie was made after them - and this is what you’re watching.