Jargon: Why Do We Sometimes Talk Funny?

Plus, would you buy a card game about office jargon?

Issue No. 33

I hope you all enjoyed the holidays. And I wish you a healthy and transformative year this year. 2024 for me was the year in which I found solace in quiet places and with good people. In 2025, I’m planning to bring in more outside perspectives to these essays, so that you’re not only hearing from me. Expect engaging interviews with interesting people. My plan for the next few issues is to cover humor and imposter syndrome, and go into how each of those things affects how we think about ourselves and the world around us.

For this issue, I figured we start the year with a lighthearted topic on jargon.

Jargon, what is it?

Jargon refers to language that’s understandable within a group of specialists, but not so much outside that group.

In the neutral-to-positive sense, it means a shorthand that helps specialists communicate efficiently, accurately, and clearly. For instance, technical terms used within a discipline like publishing, engineering, medicine, aviation, or security. We can call this good jargon.

In the negative sense, it means a shorthand that can confuse people, alienate them, or cause them to disengage. Either because it’s used outside its specialized group, or because a speaker wants to signal something through convoluted rhetoric, like them being of a certain status, or them knowing more than they actually do.

Bad jargon can impair people’s ability to process technical information, for instance.1 It can limit people’s ability to be persuaded by new ideas. And it can reduce their willingness to be involved civically or politically. Or to be involved, period.2 All those things can have the effect of monopolizing information within a certain in-group.

Interestingly, the word’s origin comes from that negative connotation.

“Jargon” derives from Old French jargon, jargoun, gargon, ghargun, and gergo, terms referring to “the inarticulate utterance of birds, or a vocal sound resembling it; twittering, chattering.”3

Here are some examples of it from different disciplines.

Restaurants. “We’re 86’ing the shrimp” means the kitchen’s removing it from the menu.

Air traffic controllers. “Alpha Bravo 23 is approaching the runway” refers to aircraft AB23. Use of the phonetic alphabet avoids confusion caused by similarly sounding letters like E and T or M and N.

Police. “187” refers to a type of crime—murder in this case. Specifically, it’s used by police in California to reference Penal Code Section 187.4 To avoid exchanges like: Calling all units, a robbery has happened. A what? A snobbery? No, Jimmy, a robbery. A slobbery? Never mind.

Hospitals. “Code blue” refers to an adult medical emergency. Health professionals use acronyms and terms, often Latin or Greek, to succinctly and precisely describe events or conditions.

Courtrooms. “Mens rea” means a mental state of intent to commit a crime. “Prima facie” means evidence that can establish a fact unless disproved. I’ve heard the second one plenty of times in other settings.

Finance. A “bear market” means a low-performing one, when stocks are trending down. A “bull market” means a high-performing one, when stocks are trending up. Consequently, “bearish” means pessimistic, inclined to sell and “bullish” means optimistic, inclined to invest.

So jargon, broadly, can be thought of as any agreed-upon shorthand within a group, such as codes, euphemisms, metaphors, analogies, turns of phrase, idioms, and acronyms that are understood by members of that group. Depending on usage and whom it’s aimed at, it can either improve communication or hinder it.

(Caveat: this is a definition that makes sense to me. There are different definitions of the term out there.)

My experience with funny language

As I prepped for this issue, I thought I’d recall from memory all the funny language from days past. (I worked an office job at technology companies for over a decade.) Within the hour I had 50 words and phrases. By the end of the day, I had upward of 130.

They were things that were accepted by existing employees and sustained by newer ones, like me, adopting them without question. Some examples were benign, self-evident phrases like,

Can we circle back on it?

Meaning, Can we talk about the thing?

Can I pick your brain real quick?

Meaning, Can I ask you a question?

Can you show a bias for action?

Meaning, Can you show initiative?

You’d probably be able to guess what those phrases mean. But how about these ones?

Will you be starting with table stakes?

Meaning, Will you start with the features that users expect the product to have? A poker reference, I later learned.

Will you be hillclimbing this quarter?

Meaning, Will you be working toward some target? As in, user growth is 60%, but we want it to be 65%, so we’ll hillclimb on that metric to get it to 65%.

Are you excited to see how the sausage is made?

Meaning, the messy inner workings of how something is put together. I genuinely was stumped when I heard that one for the first time.

Then there are sinister ones.

I’m managing [so and so] out.

Meaning, I’m getting rid of them. Discretely. Akin to the Mafia imperative, “Take care of it.” I heard that from a manager I once worked with, who I later learned had a habit of getting people to join his team only for him to “manage them out” so he could repurpose the headcount.

Then there are other examples5 that have inappropriate origins, like “opening the kimono,” which means disclosing information about the inner workings of a company. And “circling the wagons,” which means protecting a team from external threats.

With the benefit of hindsight, I really do wonder why it was necessary for us to use phrases like those, instead of just saying what we mean. There is an explanation of course.

Why do we use jargon?

It saves time. Like we said at the outset, jargon allows members of a group to convey complicated ideas succinctly and quickly. There’s no need to spend energy thinking up the right word for something, whether that thing is explicit or implied. When time is a constraint, or when mission-critical or safety-critical decisions hinge on our actions, precise shorthand keeps things moving.

It signals status. Membership in a social group often means members speak in similar ways. Jargon is that lingua franca that helps facilitate this social cohesion, for better or for worse. Companies sometimes call this factor “culture fit”—a euphemism for how easily a person can integrate into the team or company. By adopting the group’s jargon, a person is essentially signaling, “I’m one of you,” either to the group they’re in or to the one they aspire to be in.

It covers up insecurities. When we either have a gap in knowledge or are preoccupied with what others think of us, we’ll focus more on maximizing our use of impressive-sounding words, rather than on how clearly we’re communicating.6

In one study,7 business students were asked to imagine themselves pitching a business idea to venture capitals. They had to pick between two pitches—one that used lots of business jargon and one that didn’t. They were then told they’d either be competing against successful MBA alumni or regular students. When they thought they were competing against successful MBA alumni, the students were more likely to pick the pitch with lots of jargon.

How do we avoid bad jargon?

Optimize for clarity. Make clear communication an explicit goal. Maybe even pin it somewhere—clarity above all. Don’t abandon good jargon, but ensure that any language you use takes into consideration the audience you’re speaking to and aims to convey, clearly, rather than sound impressive. Define things when appropriate. If, say, an engineer is new to a company and certain company phrases will help them become productive, define those phrases—explain why they’re used and for what purpose.

Edit twice, communicate once. One thing I like to do is have someone from outside my discipline read my writing before I publish it. It’s the easiest way to filter out language that’s convoluted or makes assumptions about what an audience already knows. If you don’t know anyone, role-play being an editor. I do that too. I’ll adopt different personas, and imagine how it feels like reading, say, an email or a document. After a while, you develop an instinct for simplifying things without oversimplifying them. I don’t pretend to be there yet, but I’ve come a long way.

Show by example. A person in a position of authority can deliberately break the perceived association that some might have between high status and high jargon use. By talking and writing plainly, to the extent possible. Some of the most brilliant teachers, like Richard Feynman, captivated students who in some cases didn’t know any physics—they liked that he spoke plainly, and so they felt involved. If someone I look up to speaks in a way that’s familiar, and I’m just starting out in a field, then I’m more inclined to emulate them.

Fill our knowledge gaps. Do we have gaps in our knowledge that we’re compensating for with jargon? If so, self-awareness about something like that can help us fill those gaps.

You said something about this being a lighthearted issue?

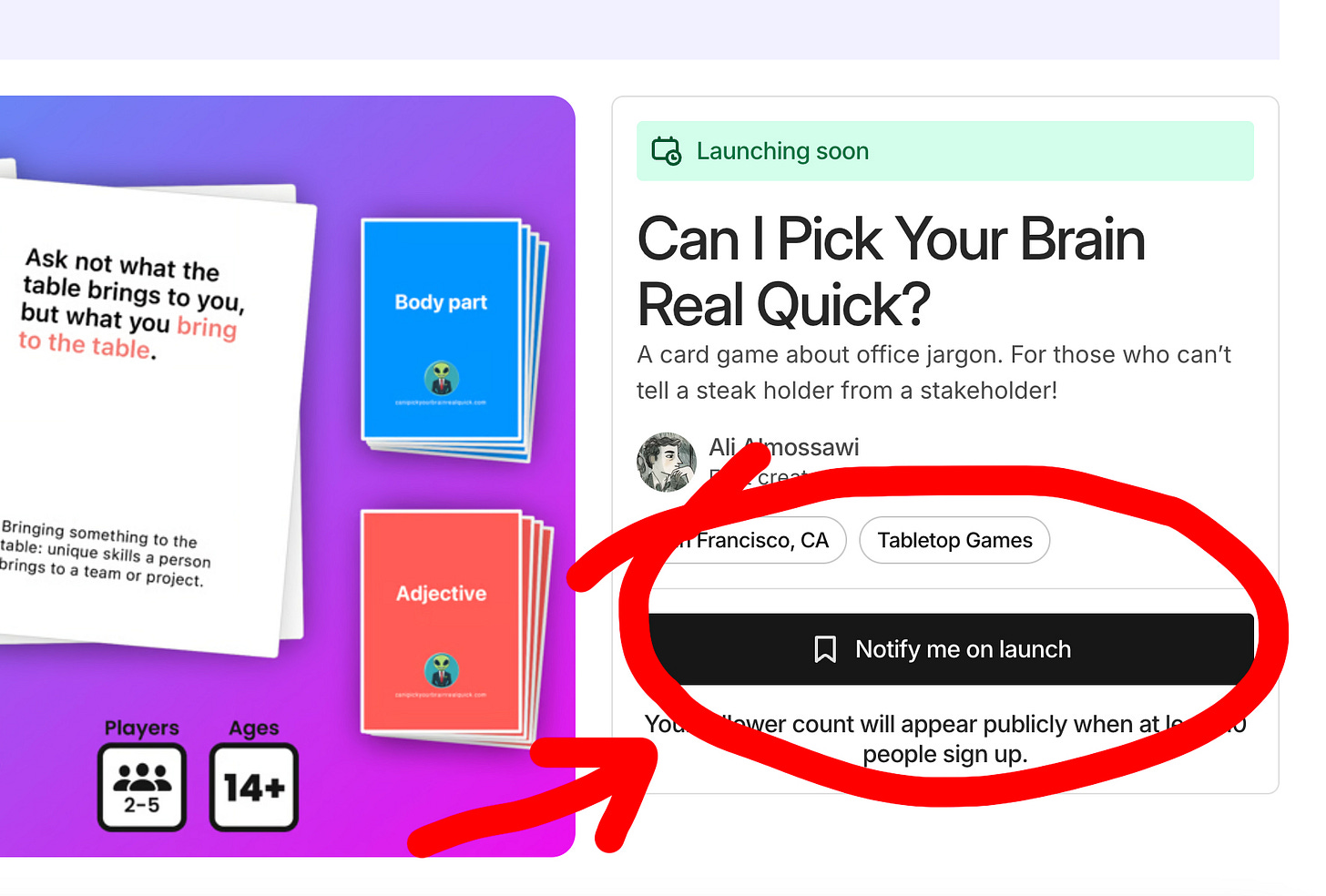

Ah, yes. Would you be interested in a card game on office jargon? As in, if I were to work with a printer to manufacture one, do you think you’d be interested in buying it?

It would be called Can I Pick Your Brain Real Quick? It would teach players about all the odd phrases people with office jobs use. Fun for those who hear this language every day. Even more fun for those who can’t tell a steak holder from a stakeholder!

There would be 135 or so cards per deck. They’d be professionally printed on high-quality paper stock by a company that specializes in card games. And the cards would come in a beautiful two-piece box.

If that sounds compelling, click on the button below and then on the Notify me on launch button on the Kickstarter page. That will give me a sense of whether there’s enough interest for this project. I’ll likely price the physical game at around $25 and give away the print-and-play version to all paid subscribers. Free shipping is doable for US orders, but would likely be extra for the rest of the world.

How the game would work

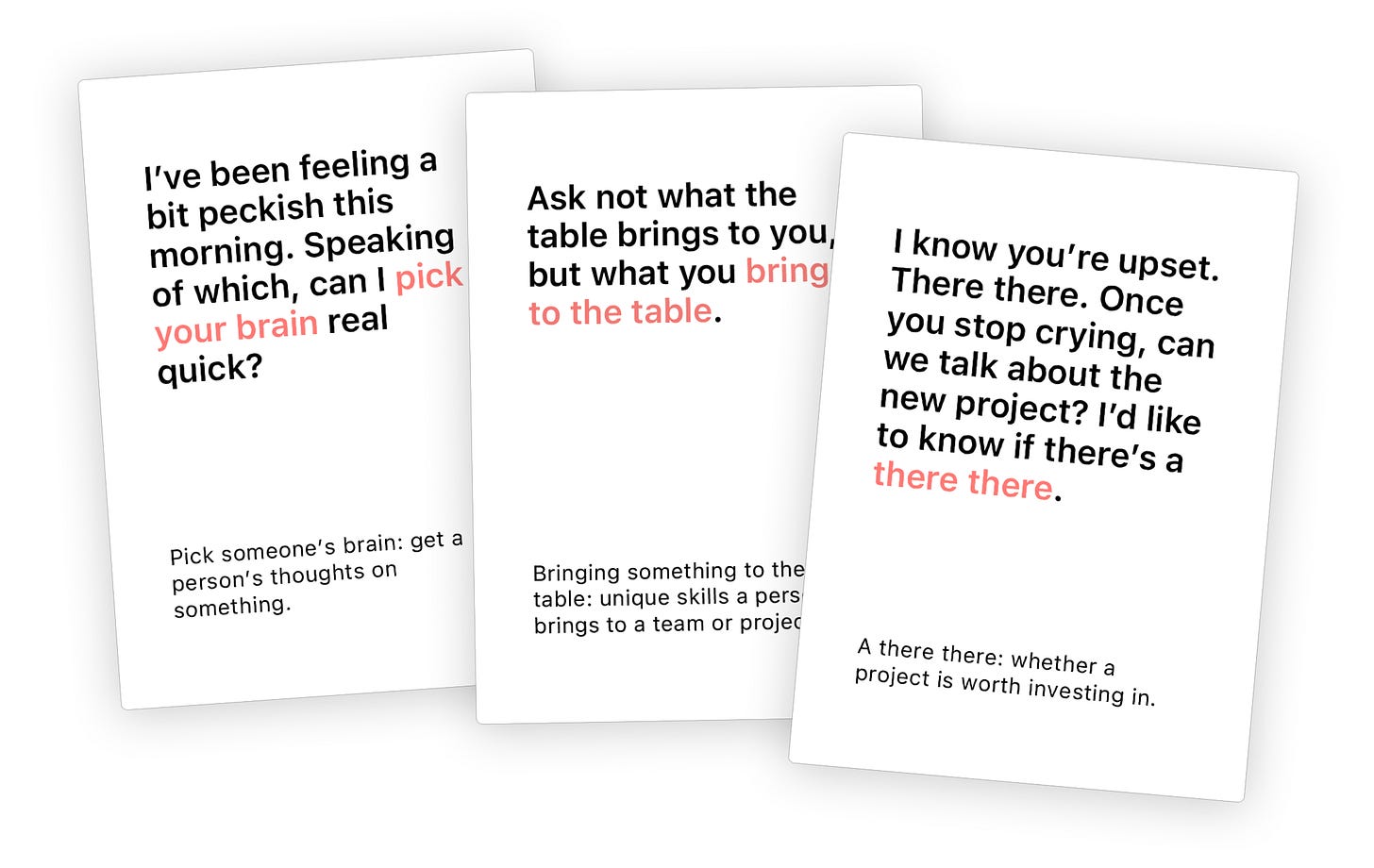

The deck would come with 135 cards. There would be 3 types of cards. 100 jargon cards that are sometimes written in a way that’s meant to throw players off.

15 adjective cards and 15 (age-appropriate) body part cards, like the ones here.

You place the 3 types of cards into 3 piles facing down. Players take turns drawing cards from the jargon pile.

You read the sentence on the card out loud to the player to your left. The other player has to guess what the word or phrase in red means. Correct answers get 1 point. (Or if you're playing with veterans, wrong answers get 1 point.) First to 10 points wins.

If you don’t know the answer to a card, you can draw 1 adjective card and 1 body part card. Make a funny quip out of the two cards to collect 1 point. Each player is allowed a maximum of 2 quips per game.

Barbara’s rhubarb bar now serves barbarians

After my sketch in last month’s issue on how the words rhubarb and barbarian come from the same Greek root word, someone asked if I’d ever heard the German rap about Barbara’s rhubarb bar. I hadn’t. Here it is in all its glory.

Want to feature your product here? Email 💌 press@almossawi.com

Piglet sidled up to Pooh from behind.

“Pooh!” he whispered.

“Yes, Piglet?”

“Nothing,” said Piglet, taking Pooh’s paw. “I just wanted to be sure of you.”

―A.A. Milne (The House at Pooh Corner)

Until next time.

Be well,

Ali

https://comm.osu.edu/sites/comm.osu.edu/files/PUS%202019-%20Bullock%20et%20al..pdf

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316627720_Varying_Metacognition_Through_Public_Opinion_Questions_How_Language_Can_Affect_Political_Engagement

The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, by way of “Scientific Jargon, Good and Bad” by Russel Hirst.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Police_code

Though not jargon, other memorable phrases are oxymorons like “somewhat precisely” (thanks, James) and “mostly a consensus.”

https://www.vulture.com/2020/02/spread-of-corporate-speak.html

https://hbr.org/2021/03/do-you-have-a-jargon-problem