How Context Switching Eats Away at Us and What to Do About It

Sorry, Gary, but can I pick your brain real quick about something? (Plus, a note about a pretty intriguing book.)

Issue No. 23

Many of us are likely familiar with this phenomenon. You’re working on a task that gets interrupted by another one. You shift your attention to the new task. Then that task gets interrupted by yet another one. You shift your attention a second time, hoping all the while to eventually, at some point in the day, work back to your unfinished ones.

But that doesn’t always happen. According to one study, 41% of office workers who had a task interrupted never went back to it,1 which means this constant shifting of attention can leave a growing trail of abandoned, half-finished work in its wake.

How often do you think the average office worker is interrupted? I didn’t know until I did the research for this issue. Once every three minutes.2 And it takes them 23 minutes to return to an interrupted task.3 Considering the alternative is zero minutes, several 23-minute blocks add up pretty quickly during the course of a day. It’s not only the extra time you have to now commit, but also the extra mental strain of having to store liminal, tacit bits of information for later recall.

Long before its colloquial usage among office workers, context switching was investigated in at least two fields. The first was in psychology. The earliest example I could find was from a 1927 book by Arthur Jersild.4 Referred to there as the problem of “set and shift,” and in which the author looked into the effects of a person constantly shifting from one task to another.

[A] person cannot attend to more than one thing at a time. To combine into one performance two or more distinct activities calls for continued shift from one mental set to another. Ordinarily it is supposed that shift of this kind entails an added expenditure of time and energy … the cost of shift is loss in efficiency.

The second was in computing. The earliest example I could find was from a 1959 paper by Christopher Strachey, though the idea was talked about up to a decade earlier. In the paper, Strachey proposes how two tasks—either programs or devices—vying for a processor’s attention are able to run, correctly and efficiently, by making optimal use of idle time.5

… the efficiency of using the machine can be much improved by having two or more programs in the machine at the same time and arranging that, effectively, the machine is never idle between programs.

A key similarity is that both humans and computers require some sort of overhead to handle context switching. Overhead that ensures the switching happens at opportune times and has no side effects.

Two key differences are that, firstly, you can upgrade a computer to make it faster, but you can’t stick a bigger chip up a human to do the same. Not at the moment, at least. And secondly, with computers, there’s no emotional cost to context switching, only a computational one—computers don’t get tired, stressed, or agitated, they don’t lose focus or morale.

Another way to think about it is that when done right, context switching helps us be more prolific by allowing us to get more work done. When done wrong, it becomes a nuisance and leaves a lasting emotional toll, which can lead to a drop in our performance and wellbeing.

What’s the impact?

We end up making more mistakes. In a study of people working on a task made up of sequential steps, an interruption as short as three seconds doubled a person’s error rate. An interruption of four seconds tripled their error rate.6 An interrupted task can be perceived as being harder than it actually is,7 which leads to stress. When we’re mentally strained, we become anxious, we start second guessing our decisions, and we start making mistakes. Several memoirs I’ve read these past few months were written by office workers who, in their effort to prove themselves in a competitive work environment or to an unreasonable boss, tried to juggle too many things at once. It led to them making mistakes, which in turn led to a loss in confidence.

Work takes longer to finish. Have you ever switched lanes in a traffic jam? If you’re anything like me, you switch to the left lane and the right one starts moving. You switch to the right one and the left one starts moving. In an attempt to go faster, we sometimes end up going slower. The switching to and from tasks, when it’s done haphazardly, can cause a loss in efficiency.8 In one study, for 30% of people who had a task interrupted, it took them two hours or more until they were able to resume their original task.9 Another showed that interruptions during times of high mental load result in especially long recovery times.10 The problem is compounded because when we’re distracted by one thing, there can be a tendency to then be distracted by other things.

We lose the ability to think deeply. It’s hard to focus when there’s a constant buzz in our ears coming from other tasks competing for our attention. Just the knowledge that they exist gnaws at us, which is why I like to do deep thinking first thing in the morning. Before I’m aware of what else is happening around me in the real world. Deep thinking can sometimes feel like trying to remember a dream you just woke up from. It’s painful when that delicate process is interrupted.

Creativity and self-reflection require stretches of uninterrupted time. They require stretches of pointless, useless work, where one is experimenting, and arranging, and consolidating disparate ideas. It’s hard to be creative when you’re putting out fires all the time. It’s hard to sit with yourself and think deep thoughts if you’re constantly distracted by something that needs to get done right away.

It burns us out. What we call burning out comes from a metaphor popularized in the ‘70s, and means exhaustion from stress, anxiety, and related feelings of frustration and apathy.11 It’s a major reason why office workers today quit their jobs.12 There are several stages to burnout. In the first, you have an environment that you identify as insidious. Then you try to work within the system to reform it. You might compensate for interruptions by working faster, which makes you feel good in the immediate term. But that only causes the stress coil within you to twist tighter, until it goes off one day, throwing you into a place of complete debilitation and apathy.13

It stunts our emotional empathy. I once worked for a manager who never looked me in the eyes during 1:1s. Not once. He was always responding to Slack messages, sending emails, checking his second monitor for one thing or another, messing with his cellphone. How attuned was he, likely, to anything I was saying, or to my body language? Likely, not at all. A face-to-face with another person is not an opportune time to context switch, and when we do, that diminishes our ability to understand, communicate, and empathize with others.

What can you do about it?

Do one thing at a time. All this constant talk of doing more, faster, better nowadays. I’m not having it! There’s something to be said about slowing down. There’s something to be said about not over-obsessing about maximal efficiency and productivity. In this little corner of the world I’m in, which may well not be reflective of other corners of the world, it does feel like there’s a frenzy around that over-obsession. “Do one thing,” as that Unix adage from 50 years ago goes, “and do it well.”

Make things more predictable. Everything I know about how restaurant kitchens work, I learned from high-stress TV shows like Bear and Gordon Ramsey’s body of work (including his latest self-help book—It’s Raw, You Doughnut! A Collection of Endearing Phrases to Say on a First Date.) A head chef can’t help but context-switch as they’re trying to keep a handle on all the moving parts around them. What helps them is predictability. Stations allocated to different tasks. A directly responsible person per station. And expectations around speed, quality, and communication.

Allocate specific times for specific types of work. Pick specific times on your calendar and block them for certain types of work. Ideally, at the same time of day so you develop the mental muscle of associating a time and a task. You’re essentially putting like items together and broadcasting when your opportune moments for being interrupted are—between these pre-defined blocks. It also broadcasts when someone might want to disrupt you for cause. For instance, you’ve dedicated an afternoon to brainstorming ideas for a new project, someone emails you a paper they think you should look at during that same hour. The two things are related. According to one study, people don’t find that sort of switching disruptive.14

Push back on urgent work. Not all important work is urgent. Workplace culture is informed by how people at the top show up and how communication happens. If the person up top talks of “putting out fires” all the time then the culture becomes one where everything needs to be handled right away. One way to push back on this sort of culture is to lay down processes and communicate that slowing down will actually help a team be productive for longer. For instance, a team sets the expectation that its work for a given week is allocated on Monday. And unplanned work can be triaged and allocated the following Monday at the earliest. And if that process is ever broken, the cost of breaking it ought to be documented and broadly communicated.

Just like our kids might unconsciously mirror our behaviors, an organization’s output might mirror how it’s structured and how it communicates.

… organizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.

—Melvin Conway, How Do Committees Invent?

Limit notifications. Notifications from our apps can lead to self-inflicted context switching by reducing our attention spans. They’re pretty low as it is. We hear a ding or our phone vibrates, and we reach for it right away. Before you know it, you’re down some rabbit hole. Our digital apps exacerbate this problem. From the few talks I’ve attended on the topic, reels and shorts on social media that do well, do well in no small part because they’re able to capture people’s attention during the first one to two seconds. That’s how fickle attention has become. The fix is to limit or eliminate these distractions.

The long and short of it

You can do multiple things at once. Just be sure you’re being deliberate about when you switch your attention from one thing to another so that you maintain your emotional sanity.

A different kind of book

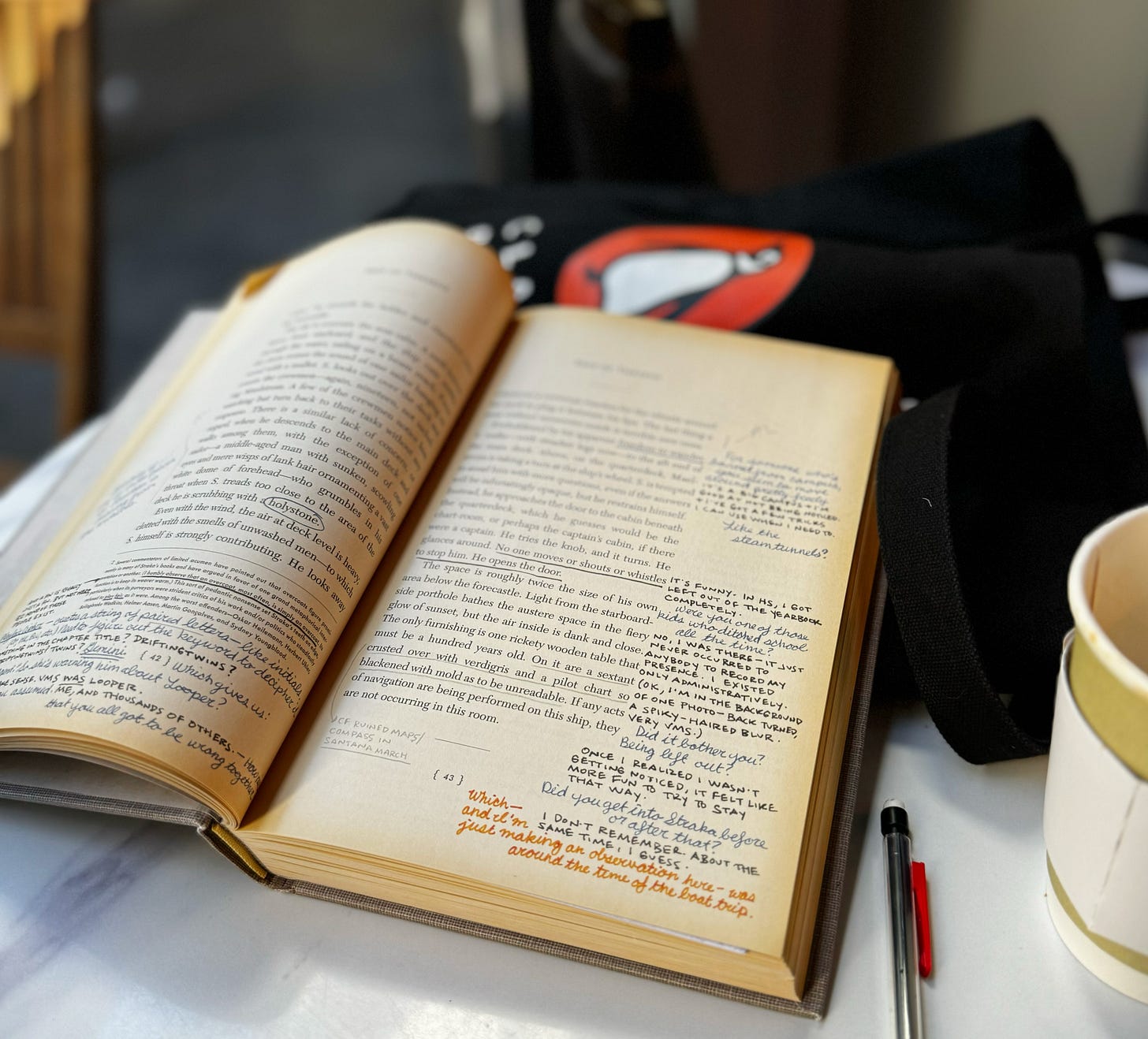

A good friend sent me a book in the mail the other day that I really enjoyed and that I figured I’d share. It’s called Ship of Theseus,* and it tells the story of a man in an overcoat trying to remember himself as he travels on board a mysterious ship from one shore to the next.

Marshall McLuhan coined the phrase “The medium is the message” to suggest that form (or conduit; human or inanimate) is as important to the message being conveyed than the content of the message. This book does an innovative thing of including handwritten marginalia between two readers who are borrowing the book, in turn, and scribbling thoughts to each other. It’s also stuffed with sketches on napkins and scraps of paper. It’s such an interesting way to enrich an age-old medium.

I won’t spoil the story for you, though I’d love to have a future essay talk about paradoxes and thought experiments like Theseus’s Paradox. Here are some of my notes.

Thumbnails. “The big sailor picks at this teeth with a filthy thumbnail.” (p.211) It never hit me that a thumbnail is quite literally the nail of a thumb. To me, it always meant that little image on a website or in an app. Its small size is where it gets its name from.

Descriptions of noses. Leptorrhine means a long, narrow nose (p.88). Aquiline means a hooked nose—“The aquiline nose that overhangs it is astonishing both in size and in the dignity it suggests.” (p.84)

The thing that gathers under your eyes sometimes. “S. can see little snakes of white hair creeping though his torrential black beard, can see the rheum that rims his eyes.” (p.55)

Occam’s razor. “S. feels something that might be relief … at least now he knows he’s not a Detective, not one of Vevoda’s men … Then it occurs to him that if he were spying for Vevoda, this would be an advantageous position: he would be a cowbird in the enemy’s nest. But the simpler story, the one most likely to be true, is that he is now a wanted man.” (p.120)

Apophenia. “You think everyone’s spying for management,” Corbeau says. “I’m probably right,” Pfeifer says. “Don’t you think it’s better to be suspicious? Especially now?” “I do,” Corbeau says, “but I also value my intuition, and I think it is very dangerous business to start doubting your intuition.” (p.117)

The medium is the message.

—Marshall McLuhan

(* This is an Amazon affiliate link. If you end up buying the book, I’ll receive a small commission. You can remove the tag at the end to turn it into a regular link.)

A blessing of his amnesia: he has no knowledge of any connections to others … How fortunate, … [t]o be a self rewritten from a lost first draft.

—Doug Dorst (Ship of Theseus)

Until next time,

Ali

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309903121_Timespace_in_the_workplace_Dealing_with_interruptions

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gloria-Mark/publication/242368653_Constant_constant_multi-tasking_craziness/links/5e239c89299bf1e1fabd4289/Constant-constant-multi-tasking-craziness.pdf

https://news.gallup.com/businessjournal/23146/too-many-interruptions-work.aspx

https://archive.org/download/mentalsetshift00jers/mentalsetshift00jers.pdf

https://archive.org/details/large-fast-computers

https://interruptions.net/literature/Altmann-JExpPsycholGen14.pdf

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221519304_Investigating_the_effectiveness_of_mental_workload_as_a_predictor_of_opportune_moments_for_interruption

Ibid.

https://www.interruptions.net/literature/Bailey-SMC00.pdf

https://www.interruptions.net/literature/Bailey-Interact01.pdf

https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2022/01/01/burnout-history-freudensberger-maslach/

https://www.inc.com/marcel-schwantes/why-are-people-really-quitting-their-jobs-burnout-tops-list-new-research-shows.html

https://ics.uci.edu/~gmark/chi08-mark.pdf

https://www.interruptions.net/literature/Bailey-Interact01.pdf

So many great reminders. I loved Deep Work and Atomic Habits, and I need these reinforcements on a regular basis so I can do my best work.

I've recently had to step away (temporarily?) from a bunch of my paying work because I ended up in "a place of complete debilitation" due to burnout, so I'm focusing on rest, recovery, and personal projects of importance to me. (I'm working, again, on a book I've been writing for many years, and I hope to get it done this time.)

I love your work as always, Ali!