Do Personal Attacks Ever Work?

Sifting through 43 political fliers pushed through my letterbox last October

Issue No. 35

Back in October, I started getting fliers in the mail from people running for city mayor. I tend to scan fliers like these and then drop them in the recycling bin. What caught my eye in this case was that an increasing number of fliers weren’t telling me why I should vote for a candidate, but rather why the other candidates were horrible choices.

Nothing about those other candidates’ policies, mind you. The focus was solely on who they were and the various terrible things they had done.

For instance,

[So and so] has never held a government job.

Someone who hasn’t done a job before can still be good at it now.

[So and so] has been unemployed for past five years.

Whether someone is unemployed has no bearing on whether their ideas for the city are good.

[So and so] faces $8,000 fine for ‘pervasive’ problems in Chinese-language newspaper ads.

Were they charged? Let’s say they were, does being fined make one disqualified from being an effective elected official?

[So and so] spent over $10 million of his family money on his campaign.

Whether someone was born into wealth has no bearing on their stated policies.

[So and so] developed property with execs charged in bribery scandal.

Was he part of the scandal? If not, what does the fact that he did something with people who were charged have to do with anything?

You get the idea.

I kept 43 fliers, and counted 16 that were focused on personal attacks against other candidates. Of the five hopefuls who were running, four of them engaged in personal attacks. I didn’t get any fliers from the fifth one, so I don’t know what sort of campaign he ran.

Does it work?

The mayoral candidate who ended up winning had more than triple the number of attack ads as the other three candidates combined. So in this case, dishing out personal attacks didn’t detract voters enough for the candidate to lose the election.

Why does it work?

We need to quickly categorize people we don’t know. Our brains have a tendency to want to rapidly filter detail and focus on salience. We’ll sometimes do that using mental approximations. We’ll assume someone who wears good clothes or who speaks eloquently must be smart. Conversely, we’ll assume someone who might have gone to jail when they were younger is forever irredeemable.1

It’s easy to wholesale discount a person with a purity test like that by going after their credibility. Easier than to acknowledge that people are multifaceted, and that when we’re evaluating whether someone is good for a role, we ought to be asking whether their ideas—their policies in the case of an elected official—are ones we believe are, ultimately, a benefit to society.

We like being in groups. I’ve always disliked the idea of groups. But one can’t deny that there’s a tribalistic instinct within us all. It makes us want to be around people who look like us—physically, ideologically, socially. Ad hominem attacks are the best way to tell us whether someone is on our team or not. And for people and societies where that instinct is strong, once someone is deemed out of the fold, nothing they could possibly say will ever matter. They’re not one of us, essentially, and so nothing else about them matters. It’s sad to see.

We’re more easily swayed by emotions than we think. When people are afraid, they’ll gravitate toward the idea of a sole savior—cape billowing in the wind, eyes fixed on the horizon. For there to be a sole savior, all the other people on offer need to be pooh-poohed somehow. So you end up with a climate where everyone is terrible, except of course for the one person who is asking for your vote.

Talking of sole saviors, a subheadline ran in a major US broadsheet a few years ago that felt like it was taken out of the Marvel Universe.

If [so and so] wins, it will be seen as the moment when the destiny of a man and his nation converged.

Rhetoric like this exacerbates a climate of fear.2 Elections shouldn’t be about one man’s destiny. They should, ideally, be about regular people, like you and me, sharing ideas, and an educated voting public picking the person with the best ideas.

Ad hominem

A common term for personal attacks is ad hominem. From the Latin for to the person. It’s when I’m in a debate or conversation with someone, and I respond to an argument they’ve just made not by engaging with what they just said, but by attacking them as a person.

For instance, using where they come from to discredit them.

Can you believe this person, coming all the way from the northern end of middle Brittany, wants to tell us, the good people of the southern end of middle Brittany, how things are done!

Or where I start pulling in other things that they’re associated with, like who their friends are or what their parents did for a living.

Of course he’s for lowering property taxes—have you seen the huge house his parents live in?

I never bring up anything to do with their ideas, like what they think of healthcare or public infrastructure. I bring up things that are emotionally charged and irrelevant.

Takeaways

Personal attacks aim to distract, deflect, divert. If you notice a personal attack, and you’re party to that discussion, ask that the discussion be refocused on the issue at hand. If you’re not—if you’re reading or listening to something—make a mental note that the discussion has veered into non-constructive territory. Personal attacks often aim to distract, to deflect, to divert. To get you to look somewhere else in an attempt to maneuver you like a boat down a river.

Be skeptical of arguments that are emotionally charged. Any time an argument riles you up, makes you want to get up and do something, ask yourself why you were suddenly overcome with that impulse. Even when it makes you want to affect good change. Break it down, think through why something made you feel that way.

When it riles you up against somebody else, ask yourself why you were made to feel that way about a stranger you’ve never met. Then work backwards from the feeling to the evidence you’ll need to justify the feeling. And if you don’t find any evidence, learn to quickly shed the feeling.

Arguments are about seeking the truth not about winning. If we’re in dialogue about something, then the question we should ask ourselves every time we open our mouths is, Does this thing help me get closer to the truth or farther from it?

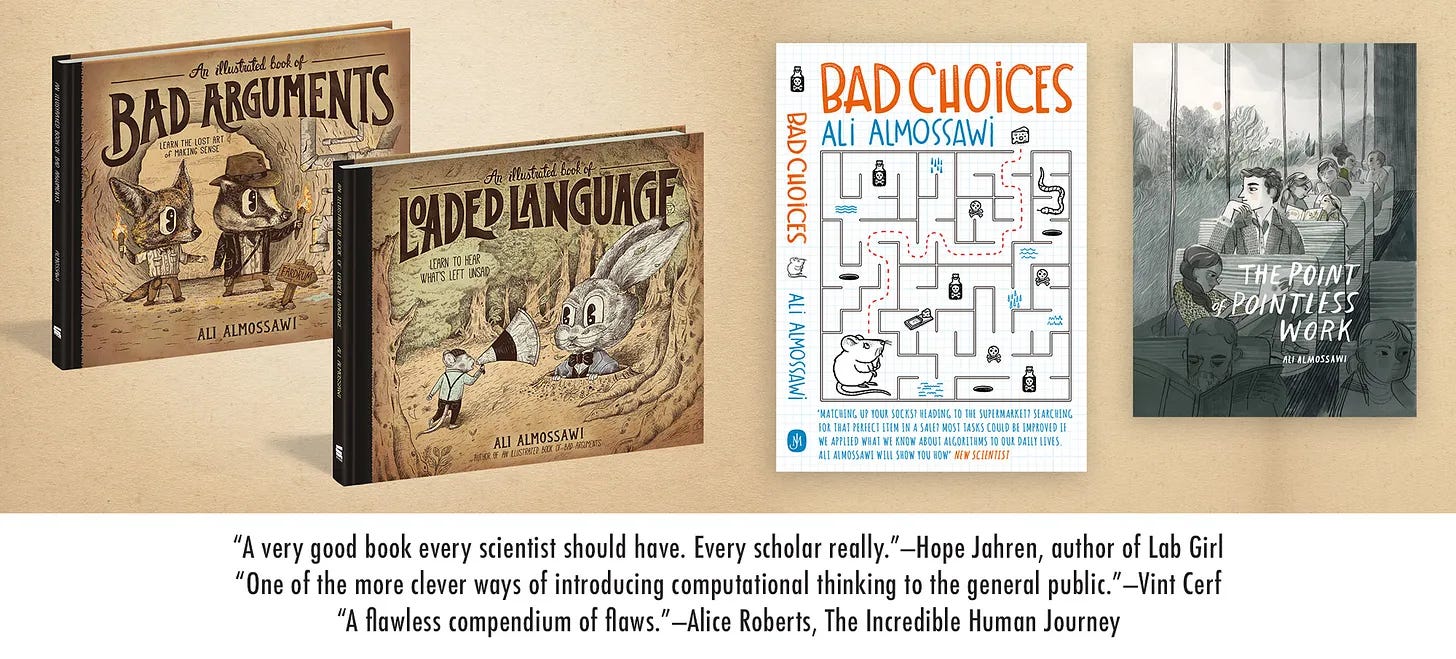

12 years ago, I wrote a book on bad arguments. The book was slow-going at first, but when it suddenly took off, a lot of people who reached out for interviews would ask me about how to win arguments. I’m not sure what I said back then. But were I asked today, I’d say that I don’t think we should ever be focused on winning arguments.

We should be open to being wrong. we should cultivate that self-awareness. I feel personal attacks often stem from the belief that a person has to win at all costs. That they have to DESTROY their opponents. CRUSH their adversaries. DEMOLISH others. You see it in the titles of clickbait YouTube videos all the time.

Why do we need to constantly crush and destroy each other?

Words can be like X-rays if you use them properly—they’ll go through anything. You read and you’re pierced … That’s one of the things I try to teach my students—how to write piercingly.

―Aldous Huxley (Brave New World)

Until next time.

Be well,

Ali

P.S. Welcome to all the new subscribers who joined from

and . Thank you, both, for the recommendations. And thank you to everyone who continues to share these issues.P.P.S. Check out the last issue in case you missed it, where I talk to comedian Brian Regan about wordplay and kindness. The next issue will be my first ever video interview with a guest.

See Well he would, wouldn’t he? for an interesting read.

One foretold in the scattered scrolls of El Dorado … where a man (in a suit) is prophesied to reveal himself and save an exhausted nation from impending doom.

"Why do we need to constantly crush and destroy each other?" Because we're now getting crushed by those who have insulted their way to authority :( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-gl-eV-TOY