The Motte and Bailey Fallacy

Plus, irrelevant possessive nouns and adjectives, and graphics that don't align with a reader's mental model

Issue No. 10

A very warm welcome to the 70 new subscribers who join us this week. It’s wonderful having you here.

Paid subscribers, you can now listen to issue no. 9 on dehumanizing language. It also includes a reading from Ursula Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas”. A story that’s relevant to the topic and that I really love. It starts at minute 10.30. I’ve shared that reading of Omelas over on YouTube as well.

1 Reasoning

The motte and bailey fallacy

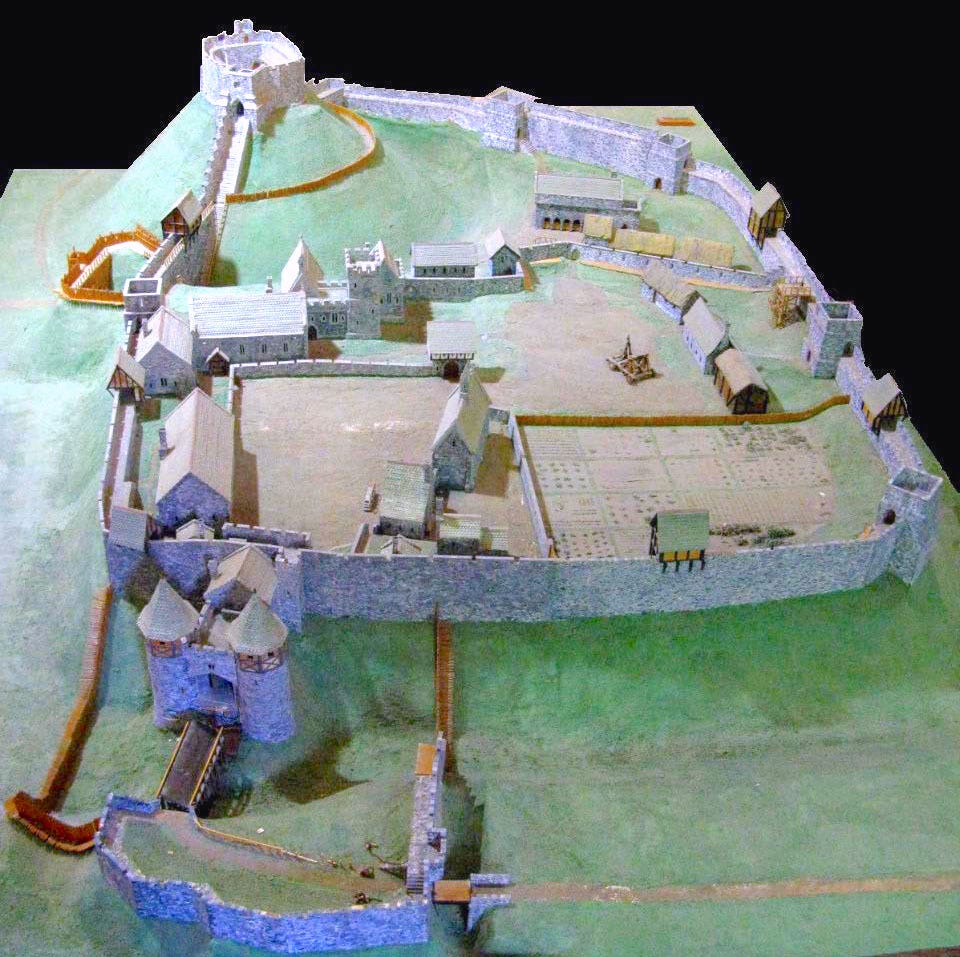

From the 10th century onwards, a type of castle was built in Europe known as the motte and bailey castle. The bailey was a walled yard, often surrounded on the outside by a ditch. The motte was a mound on which a fortified tower sat. As in the image below. If an attacker tried to breach the castle with large numbers, the bailey wasn’t all that defendable. And so one would have to run up the motte to the tower and defend the bailey from that superior vantage. Once the attacking army was no longer a threat, one could run back down to the bailey and chill.

In a paper in 2005, Nicholas Shackel used the example of the motte and bailey castle to suggest a certain framing for a type of insincere logical argument.

For my purposes the desirable but only lightly defensible territory of the Motte and Bailey castle, that is to say, the Bailey, represents a philosophical doctrine or position with similar properties: desirable to its proponent but only lightly defensible. The Motte is the defensible but undesired position to which one retreats when hard pressed.

An entire doctrine or theory may be a Motte and Bailey Doctrine just by virtue of having a central core of defensible but not terribly interesting or original doctrines surrounded by a region of exciting but only lightly defensible doctrines. Just as the medieval Motte was often constructed by the stonemasons art from stone in the surrounding land, the Motte of dull but defensible doctrines is often constructed by the use of the sophists art from the desired but indefensible doctrines lying within the ditch.

—Nicholas Shackel (The Vacuity of Postmodernist Methodology)

In other words, I make some claim that’s hard to defend (the bailey). Once pressed, I change the claim with a sleight of hand to one that’s less controversial, but shares similarities with the original one (I run up the motte). And once I convince you of the less controversial claim, I switch back to the original claim and declare victory (I run down to the bailey again).

For instance, a standup comedian once shared the line, Here’s an idea for staying fit, just eat salads. It’s a brazen line. You might respond with data showing that for some people, no matter how well they regulate their diet, they have a predisposition to obesity for a variety of reasons. The arguer might counter with,

All I’m saying is that healthy people eat healthy food

That second argument sounds similar to the first one. But it’s not nearly as brazen. It’s true, healthy people likely do eat healthy food, and are likely also active and regulate their stress levels well. But that’s not what the original argument was about. The original argument was that an obese person is only obese because they refuse to eat salads. If the person can get you to accept the second argument (the motte), they might then assume they were able to convince you of the first one too (the bailey).

In this example, the sleight of hand takes the shape of plausible clarification—All I’m saying is, and then the target shifts to something else. A legitimate clarification is not a fallacy, and is a natural part of good-faith discourse.

A related sleight of hand happens with redefinition. Where one equivocates on a word and changes its definition depending on which definition is most advantageous to them at the time, or perhaps which audience they’re talking to. An example of that is the word enemy during a conflict, where one might define it in two ways: one, as both combatants and civilians (the bailey), and two, as only combatants (the motte). If the belligerent is ever pressed on civilian deaths, it’ll switch to the second definition and express its regret for the civilian toll. And at all other times, it’ll operate in practice on its first definition.

There’s a memorable example of this sort of redefinition in Through the Looking Glass. I was delighted to see that the paper from above cites part of the passage. I’ll cite a bit more of it here. Alice is having a conversation with Humpty Dumpty and the following exchange takes place between them:

‘And only one for birthday presents, you know. There’s glory for you!’

‘I don't know what you mean by “glory,”’ Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. ‘Of course you don’t—till I tell you. I meant “there's a nice knock-down argument for you!”’

‘But “glory” doesn’t mean “a nice knock-down argument,”’ Alice objected.

‘When I use a word,' Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master—that’s all.’

Alice was too much puzzled to say anything, so after a minute Humpty Dumpty began again. ‘They’ve a temper, some of them—particularly verbs, they’re the proudest—adjectives you can do anything with, but not verbs—however, I can manage the whole lot of them! Impenetrability! That’s what I say!’

‘Would you tell me, please,’ said Alice ‘what that means?’

‘Now you talk like a reasonable child,’ said Humpty Dumpty, looking very much pleased. ‘I meant by “impenetrability” that we've had enough of that subject, and it would be just as well if you'd mention what you mean to do next, as I suppose you don't mean to stop here all the rest of your life.’

‘That's a great deal to make one word mean,’ Alice said in a thoughtful tone.

‘When I make a word do a lot of work like that,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘I always pay it extra.’

‘Oh!’ said Alice. She was too much puzzled to make any other remark.

—Lewis Carroll (Through the Looking Glass)

Humpty Dumpty is essentially saying that he’s at liberty to arbitrarily redefine words at will. As in, to run up and down the motte, between controversial and trivial arguments, as the situation dictates, shifting the target the whole while, muddying thinking, and making it terribly difficult to keep track of which argument is being defended at any given point in time.

Another related sleight of hand you might see has the endearing name, No True Scotsman. A general claim may sometimes be made about a category of things. When faced with evidence challenging that claim, rather than accepting or rejecting the evidence, this sort of argument counters the challenge by arbitrarily redefining the criteria for membership into that category.

The fallacy was coined by Antony Flew in Thinking about Thinking, where he gives the following example: Hamish (it’s always Hamish for some reason) is reading the newspaper and comes across a story about an Englishman who has committed a heinous crime, to which he reacts by saying, “No Scotsman would do such a thing” (the bailey). The next day, he comes across a story about a Scotsman who has committed an even worse crime. Instead of amending his claim about Scotsmen, he reacts by saying, “No true Scotsman would do such a thing” (the motte).

What does true mean? As in the previous examples, it can mean anything the arguer wants it to mean, making whatever claim they’re putting forth easily defensible. The moment you press the arguer, they’ll merely redefine things again. And when the claim is watered down enough to something banal and you give up, if they’re insincere they’ll claim victory for their original claim that “No Scotsman would do such a thing.”

You’ll find other names for arguments that fit the motte-and-bailey model. The real human lesson for me is that a discussion is pointless if one or both sides enter into it with insincerity, or if either side’s goal is to merely score points, to prove themselves right and the other person wrong despite the evidence. Knowing about arguments that use the sleights of hand we’ve seen here is useful because you can then spot such attempts at insincerity. And they’re equally useful for realizing when we ourselves are following a line of thinking that has us blindly sticking to some original position.

2 Rethinking Language

Irrelevant possessive nouns and adjectives

A short reminder on language this week. I’ve seen quite a few examples in the news of possessive nouns being used to either discredit a fact being reported or as a form of slight against a person or a group of people. An attempt to discredit the message by discrediting the messenger.

Say I love strawberries. One day, news breaks that strawberries are becoming more expensive. Everyone reports it, including a controversial reporter named John Doe. I really don’t want that news to be true, and so I run the following headline:

John Doe-run news outlet says strawberries are getting more expensive

Now anybody who also doesn’t like John Doe might be inclined to dismiss the news as suspicious because, hey, John Doe is attached to it. A headline achieves the same effect when it says something like Democrat-run agency did so and so, or Labour-run committee determined such and so.

A while back, I made a note of the following headline:

Disney Loses Over $100 Million from Chris Evans’ Lightyear (Report)

The story was that a Disney movie had lost $100 million. The name of the lead actor in the movie felt irrelevant, unless there was a definitive causal link between the actor and the movie’s performance.

Be wary of possessives that aim to prime you with irrelevant information.

3 Rethinking Images

Graphics that don’t align with a reader's mental model

I was watching an event announcing a new computer processor earlier in the week—the M3. In demonstrating how big a leap in performance the M3 offered over its predecessors, the presentation showed a series of graphics, each comparing the percentage improvement of this new processor over the two previous ones.

One thing that struck me about these graphics was that in the few seconds I had to interpret them, something about them made them difficult to process. I realized after the fact that the difficulty was due to how sentences are constructed in English and how we perceive things that are in close proximity to one another.

Sentences in the English language usually start with a subject—the person or thing that the sentence is about. In reading the line “40% faster”, it was unclear what the subject was. It ought to be the M3 processor, since that’s what the event is about, but the line appears next to M2. And we perceive things that are close to each other in a graphic as being part of the same group (see Gestalt’s principles of grouping).

Because sentences in English start with a subject, because the language is written left-to-right, and because we assume two labels that are close to each other belong to the same group or concept, it’s not unreasonable to assume the takeaway is “M2 is 40% faster”. The exact opposite message the slide intends to convey.

With a tiny tweak, one can address that confusion. The sketch below offers an idea. The takeaways are now clearly spelled out. “M3 is 40% faster than M2”, and is lined up with the tip of the bar for M2. Similarly, “M3 is 60% faster than M1”, and is lined up with the tip of the bar for M1. There’s value in having vertical bars in this case to leverage the mental model readers will have, that the thing on the right came after the thing on the left.

Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird

That cannot fly.

—Langston Hughes

Until next time,

—Ali

Both are misdirections but really not the same thing. Super clear now. Thanks!

Motte and Bailey seems related to a Straw Man argument. Are they one in the same?