Issue No. 27

Incredulity. The state of being unwilling or unable to believe something.

I was watching a TV show the other night in which the plot twist involves an otherwise benign looking person confessing to a crime. And then talking about the feeling of dissociation they’d experienced right after. A condition I’ve come to learn is defined in a number of ways, but in that case referred to the person developing a sort of amnesia causing them to forget they ever committed that heinous act.

In their mind, they couldn’t have done it, no matter the impulse they felt at the time. So through a Hail Mary trauma response they’d convinced themselves that they, in fact, never did it to begin with.

There’s a type of argument called the argument from incredulity, in which we determine that something couldn’t have happened either because we find it hard to believe or because we don’t want to come to terms with it being true.

For instance, a person might say, It’s impossible to imagine that we actually landed on the moon, therefore it never happened. We’re essentially saying because our personal model of the world can’t make sense of this thing having happened, rather than us modifying or abandoning our model, we deny the thing ever happened.

Another person might say, I can’t believe our decisions led to so much human heartache, therefore the heartache can’t have happened. In this case, we’re fighting to reconcile two conflicting beliefs within us, and in an attempt to resolve that contradiction, we reject what we’re witnessing first-hand to hang onto a deep-seated belief.

This to me is the more troubling manifestation of the argument.

Richard Feynman alludes to this general idea in one of his lectures when he says, tongue-in-cheek.

I can safely say that nobody understands Quantum Mechanics.

—The Character of Physical Law

The implication is that not everything can be explained or reasoned about through common sense or by analogy. Some scientific explanations are counterintuitive, or might feel like magic, or might feel incomprehensible whether or not someone is technically engrossed in the field or trained in it.

One serious effect of this form of argument is that is paves the way for alternate explanations that are also not supported by evidence. If we take the human heartache example, for instance, not only would one claim that our policies didn’t hurt people but that those who appear to have suffered are embellishing and exaggerating. That it’s all a ruse of some sort. That’s how we explain things away.

The ideas shared in issue no. 24 may be helpful in countering arguments from incredulity. The Socratic method in particular comes to mind. That is, getting someone to answer a series of questions in order to get them to either realize the truth mid-way or contradict themselves out loud, which can sometimes trigger an epiphany.

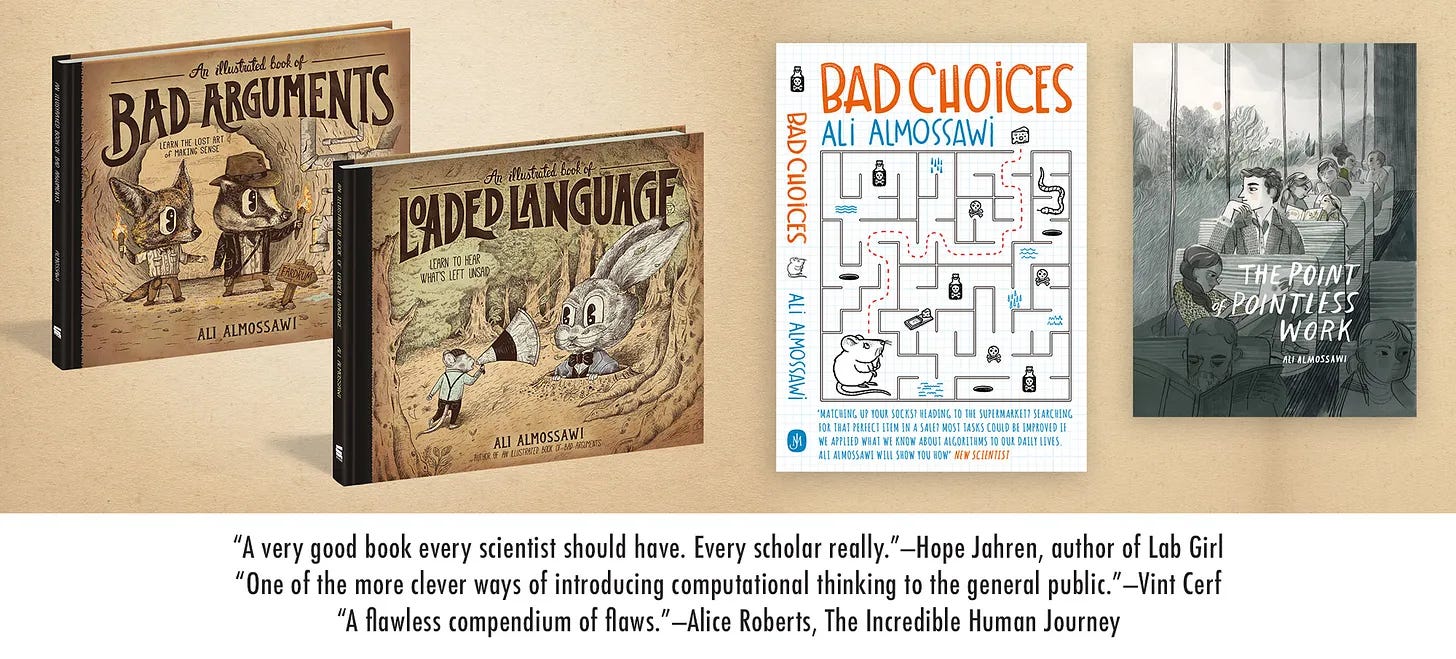

Someone reached out to me and asked if I had a list of books worth sharing. I picked five memorable books I read early in life.

Impro: I bought this book to learn about improvisation and the theatre, but like all memorable books, it taught me about other things too. About spontaneity and how freeing ourselves from the constraint of wanting to seem smart or original allows us to better connect with others.

Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!: I read this book during my last year in college. I finished it in one day and figured there was no better personification for teaching in an unconventional way than the book’s namesake. There’s this one story about people attending his talks, being totally mesmerized, and then not being able to recall what the lesson was about afterward. How we say something really is more important than what we say.

Tesla: Man Out of Time: This book gave me an appreciation for how diverse learning and learning strategies are. By his account at least, Tesla was able to imagine (or dream of?) the design of a working machine, down to its tiniest details, and then open his eyes and build it. And it would work. His approach was different from Edison’s, whom he criticized as diligent but slow and inefficient. This made me appreciate both approaches to problem-solving.

Comparisons: I understand better by sketching things on paper. Someone on the Internet recommended that I get ahold of this book many years ago, and I’m glad I did. It’s an encyclopedia of facts, but all explained using relative magnitudes. So instead of telling me a giraffe is this tall, I get to see it relative to a horse. I love that way of teaching.

Understanding Comics: I bought this book when I first got into the field of data visualization. I wasn’t planning on learning how to create comics; I just wanted to see how someone from a different discipline—a comic artist—thought about position, color, meaning, and communicating a whole lot of things in a compact format.

We have not met, I believe, frequently enough for either of us to have taken root in the other’s conscious memory. So please forgive any impertinence …

—What Do You Care What Other People Think?

(From a letter written by Henry Bethe to Mrs. Feynman)

Until next time.

Be well,

Ali

P.S. Here’s a 60-second video of how I made the book earrings from last time. (YouTube Short, Instagram Reel)

P.P.S. This issue’s feature photo is CC the Robert Treat Paine Estate. The book links are affiliate links.

I feel like another important element is that, while in some cases the premise may be objectively "hard to grasp", in most cases there is another factor in play and that is the projection of one's capacity of grasping concepts onto others. So for example, in an extreme case where a murder suspect's parent is questioned, the parent could possibly say "my son could never..." - with an implication of: if I can't conceive it happening, then no one else could either. Maybe avoiding this fallacy is difficult because to avoid it is to accept that we are flawed as people and have internal biases, and that our internal believes about what is and isn't conceivable is as unreliable as the next person's.