Slippery Slopes, "It's Complicated", and The Trouble with Some Infographics

Plus, you can now listen to the last issue on false dilemmas

Issue No. 7

I’m happy to bring you the very first audio version of an issue. This one’s of issue no. 6 on false dilemmas. It’s been really fun experimenting with that format, and riffing on things like the quote at the end. I’ll start publishing audio versions of back issues in the coming weeks. Paid subscribers will receive a separate email for them as they’re released. And for forthcoming issues, paid subscribers will receive them the week after an issue is released.

Two other notes. Firstly, the upcoming musical short is on slippery slopes, but it will have to wait for an issue or two, sadly—I ran out of time this week. What I’ll do going forward is plan to share a new musical short every few issues. Secondly, I love reading your thoughtful comments and replying to them. Keep them coming. It’s a wonderful way to continue and expand the conversation, and helps me see things in new ways.

1 Reasoning

Slippery slopes

Many will have heard of the snowball effect. The idea that our minds can start with a germ of a worry, then ruminate, letting that worry fester. And before long, it turns into a catastrophic thought that completely debilitates us. You think you’ll do badly on a presentation the next morning, and by midnight, you’re resigned to your fate—a jobless, penniless life.

What children and adults who are prone to that sort of thinking are told, is to stop ideas that snowball in their tracks, by recognizing that something possibly happening in the future is not the same thing as the thing definitely happening. That way, a person isn’t paralyzed with fear from taking on a new challenge.

In critical thinking, there’s a pattern known as the slippery slope, which similarly, assumes without evidence that a chain of events will inevitably happen. And here too, since we’re told the last event in the chain will definitely take place, we’re asked to eliminate the first event from ever taking place.

Whereas with the snowball effect, the goal of stopping a thing from happening is to empower a person (a good thing), with the slippery slope, the goal is to disempower a person (usually, a bad thing), which is why it’s a troublesome line of reasoning. As one crafty middle-schooler demonstrates.

Mom: We said nobody come over. [Your brother] knew the rules.

Greg: Yeah, but Mom, if you punish him, Rodrick’s gonna know I told on him … if you do this, Rodrick and I will never, ever be friends again. The idea that … one day, my kids won’t get to know their Uncle Rodrick or have any family holidays?

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Rodrick Rules

Greg’s mom falls for it in this example. She gives in.

Think back to any societal change that uprooted an accepted norm, and you’ll find some form of the slippery slope deployed as a discouraging tactic. A picture of some dismal future will be painted and you’ll be told that the image is your and everybody else’s lot unless you call it quits right now.

In a play about America’s founding, there’s a scene where a disappointed King George III reminds the revolutionaries of what’s to come should they secede from Great Britain. He sneakily throws in a little slippery slope to try and get those rebels to abandon their aspirations for independence—you won’t know how to lead, you’ll be alone, your people will hate you.

I’m so blue

I thought that we made an arrangement when you went away

You were mine to subdue

Well, even despite our estrangement

I’ve got a small query for youWhat comes next?

You’ve been freed

Do you know how hard it is to lead?

You’re on your own

Awesome, wow!

Do you have a clue what happens now?Oceans rise

Empires fall

It’s much harder when it’s all your call

All alone, across the sea

When your people say they hate you

Don’t come crawling back to me—Lin-manuel Miranda (Hamilton)

To protect yourself from slippery slopes, be on the lookout for things that make you go, Well, that escalated quickly. Unless there’s evidence to support that escalation at every step of the way, it’s most likely a scare tactic.

2 Rethinking Language

It’s complicated

Last time, we covered false dilemmas, and how they can be used to oversimplify the world around us. Other times, language can do the opposite. It can overcomplicate something that’s fairly straightforward. Or rather, make it seem like it’s overly complicated. One reason for doing this is to portray a situation as so nuanced and so messy and multifactorial, that it’s impossible to take a moral or factual stance on it.

For instance, on a television show, a lawyer—Jimmy—is standing before a judge, defending a client. The client has been coerced by a cartel boss—Salamanca—into saying that a gun found at a crime scene belonged to the client and not to Salamanca. Jimmy tries, unconvincingly, to make that case.

Judge: Look, there was only one set of prints on the gun. Salamanca’s. How’s that gonna happen if it wasn’t his?

Jimmy: That’s not really for my client to say, now, is it? He’s not a forensics expert. Who knows? Maybe it, uh, fell from a passing bird’s beak. And Mr. Salamanca caught it, tried to throw it away. The possibilities are endless.

Better Call Saul, Season 2, Episode 7

What Jimmy is saying is it’s complicated. There are all sorts of things that could have happened. Why assume the simplest explanation is the most probable? What Jimmy leaves out is that different explanations have different likelihood’s of occurring. And unless evidence sways us in one particular direction, when deciding if something is true or not, what we’ll often be comparing is the likelihoods of two things happening. In this case, a passing bird dropping the gun on Salamanca is slightly less likely than Salamanca holding the gun of his own volition.

Headlines might use that approach to get you to click on them, and the moment you do, you realize the topic isn’t as complicated as you were made to think. Searching Google News for the phrase “It’s complicated” brings up 57,000 headlines. Here’s one picked at random:

How much do [workers] really get paid? It’s complicated

Clicking through, one reads in the article that the answer to the question is: Mid-career, $89,000 when considering base salary, $98,000 when considering base salary and benefits, and then up to $20,000 per year once a person retires.

Another article in that list has a similarly constructed headline.

How do Philadelphia teens use social media? It’s complicated

Clicking through, we find the following explanatory line.

“It’s definitely a diverse mix, some people have it purely just to communicate and other people just sit there scrolling through the app mindlessly for hours,” Nieves said.

With this article, the phrase is used to mean that there are multiple answers to the question in the headline. Not that the question is beyond comprehension, just that different people said different things. Both these examples do a disservice to the reader—they lure the reader in by painting something as somewhat unknowable, in need of an expert to dispel. And then they misdirect.

Other times, we find that the approach is used as a sort of defense mechanism against a person’s unwillingness or inability to admit they were wrong about something. Two years ago, the US Capitol was breached. In a television interview with a congressman, he was asked who bore responsibility for the siege.

I … think everybody across this country has some responsibility … What do we write on our social media? What do we say to one another? How do we disagree and still not be agreeable even when it comes to opinion?

What the congressman is saying is that it’s not possible to only lay the blame at the feet of those who participated, bodily, in the act. Instead, every person is complicit in some form. The congressman’s appeal to objectivity here is misplaced. It misattributes responsibility by appearing to be objective.

Similarly, an op-ed in The Washington Post from last week carried the headline,

Who is responsible for the [such and such] disaster? Everyone.

There too, we find a sort of dispersing of responsibility, by equating the individual contributions of several actors over the course of a decade.

An exercise I find useful for spotting questionable uses of the it’s complicated approach is to see how someone talks about a topic that challenges their core beliefs. Whenever challenged, the open mind reacts to that momentary dissonance by reevaluating its position. The not-so-open mind can double down and reach for things like language to misdirect.

3 Rethinking Images

The trouble with some infographics

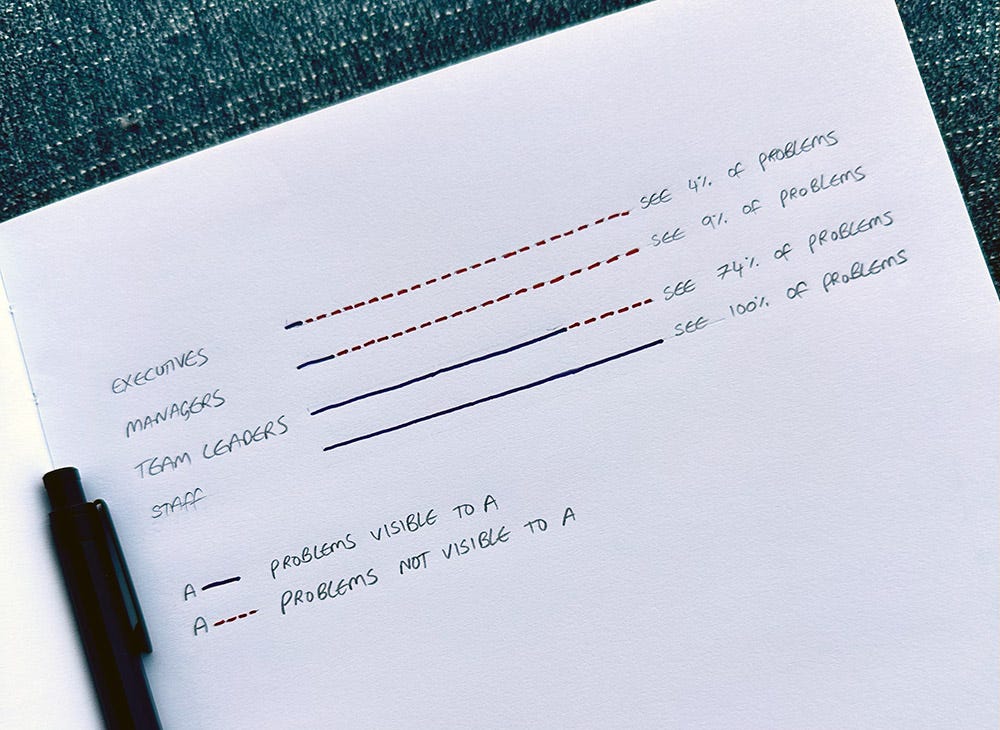

Not too long ago, the infographic below made the rounds online. The idea it was representing was that of variable transparency in an organization—how some employees see more of an organization’s problems than others. The rank-and-file in the organization see all the problems and executives see very few of them.

Taking the study as read, and scrutinizing just the graphic, the following things stand out to me about it.

Firstly, the metaphor being used is that of an iceberg. An iceberg’s most salient symbolic quality is that it poses a danger to passing ships, who see the tip and don’t realize there’s more than meets the eye. That ominous emotion is lost here, since we’re looking at the whole iceberg, in profile. The addition of a tiny approaching boat, or a change in perspective would have helped accentuate this quality of not seeing the whole thing.

Secondly, the story being told by the graphic doesn’t match the story being told by the text. The text tells us that 4% of the tip is visible, but it looks like much more of the iceberg is above water. Team managers see 9% of problems, team leaders see 74% of them, and staff see 100% of them, but the curly brackets are all the same size. We’d expect the bottom-most curly bracket to point to the entire height of the iceberg, the second-bottom-most one to point to three-quarters of it, and so on. Every such misalignment causes the reader to doubt their ability to interpret and understand.

Thirdly, there’s a conflation between senior management and executives. As in, two labels refer to the same concept using different terms. A reader might rightfully ask what the introduction of a new term—senior management—brings that the original term—executives—doesn’t. Any time there’s an implied conflation of this sort, one that isn’t spelled out, it puts the burden of assuming things on the reader. Several of those in an image, and one risks confusing a reader altogether.

One idea for making this graphic more insightful would be to do away with the metaphor and redo the graphic like so.

(There’s much more to say on the use of metaphors and analogies for visualizing quantitive data. I’m thinking of covering that in one of the upcoming long-form issues.)

Those into whose lives you are born do not pass away, he would like to inform whoever composed the question. You bear them with you, as you hope to be borne by those who come after you. But there is no space on the form for extended answers.*

—J. M. Coetzee (Slow Man)

Next time, we’ll cover the anchoring bias, concealing with apparent precision in language, and why slope graphs are good for showing change over time.

Until then,

—Ali

* There’s a JavaScript analog to the idea in that quote. A complimentary one-month subscription for anyone who lets me know in the comments what it is. I’ll share it next time if no one gets it. :)

Interesting how spotting a logical fallacy in your own way of thinking can help counter self destructive thoughts. The slippery slope tactic seems to be similar to the train of thought adapted by those who have anxiety. This might relate more to the second part - but I remember when I was younger I had a slight fear of rollercoasters. I loved them, but we went to this … questionable theme park once - where the structure of the rides did not look reliable at all. I kept thinking what if the ride breaks down while I am on it, what if I fall off to the street, etc. Then I just started attaching percentages to each thought - it hasn’t happened to anyone before you, and it has been running for years. That kind of forces me out of my own biases (to some extent, technically my percentages might be subjective too).

Also is the concept in the quote referring to recursion?